How immigration is shaping Chinese society

Main findings and recommendations

- Foreign immigration in China is becoming more diverse. While the number of high-earning expatriates from developed countries has peaked, China attracts more students than ever from all over the world, including many from lesser developed countries. Low-skilled labor and marriage migration are also on the rise.

- While the management of these immigration flows should be left to local authorities, a national framework would help guarantee the legal rights for these migrants. International cooperation with the countries of origin and with relevant international organizations would ensure that standards are upheld, also for irregularly residing, married, or employed foreigners.

- Policies to attract high-skilled foreigners have helped China to become a science and technology world-leading power. However, this has recently started to backfire. In the US, China’s efforts to enlist US-based, often ethnic Chinese researchers to China’s science and innovation drive have attracted a sharp response from the federal authorities.

- It is in the interest of China and the talent migrants themselves to develop common standards for recruitment and transparency regarding international research collaboration and the publicly financed grants and projects involved.

- To many foreigners, China in the last ten years has become considerably less accommodating, particularly regarding border management, public security, visa categories, work and residence permits. There is an urgent need for fo- reign governments to disseminate accurate information on the rights, duties and procedures that foreign residents in China should follow.

- Immigration policy needs to include the integration of foreigners into society and provide clear and predictable paths to acquiring permanent residence. Foreign governments and international organizations could insist on full reciprocity between the treatment and position of foreigners in China and of Chinese abroad.

- The trend towards intolerance to ethnic and racial difference, fed by increasing nationalism and ethnic chauvinism, is worrying. The Chinese government, civil society, foreign diplomatic missions, employers of foreigners and international organizations present in China should take a clear stance against racism and discrimination.

- Population aging, the shrinking of the work force and ultimately of the total population require a strategic and long-term view on the volume and types of foreign immigration that are needed and sustainable. As China considers its demographic future, both migrant source and other migrant destination countries need to be able to respond to brain, skills and labor drains to China.

1. Foreign residence in China: Coming to terms with new types of diversity

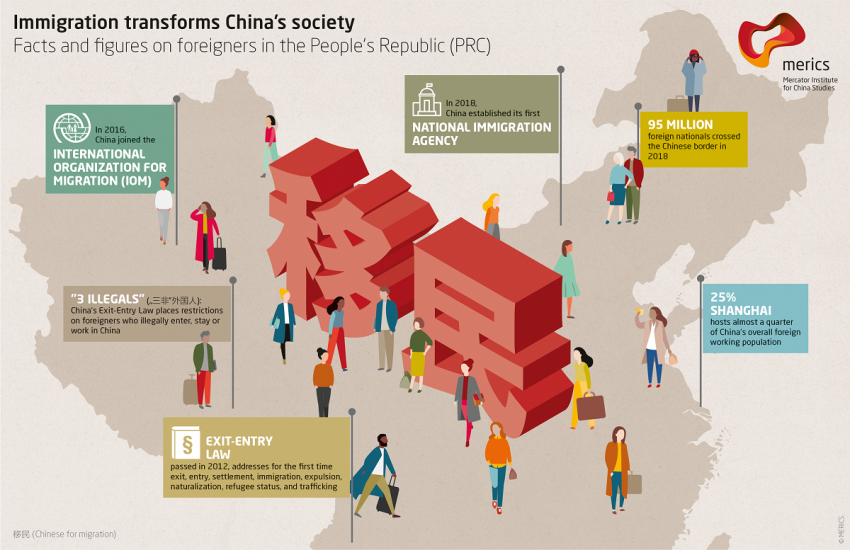

Internal migration and large-scale urbanization have been fundamental to China’s economic success story. The country’s development has given rise to massive flows of both domestic migration and international emigration. Recently, China has also emerged as an immigration destination country. In 2018, both the number of border crossings in and out of China by mainland citizens (340 million crossings) and foreign nationals (95 million) reached record heights.2

According to the 2010 census, which for the first time included foreign residents, China currently has a foreign population of one million. Estimates that include the many non-registered non-PRC nationals add up to double that figure. While this still is a minute fraction of China’s total population of 1.34 billion, the absolute number already makes China an immigration country the size of a mid- sized European or Asian country.

Foreign residents in China include students, expatriate or locally hired professionals, entrepreneurs, traders, marriage migrants, and unskilled laborers. They include ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese foreigners. They are both from the PRC’s neighbors (mainly South and North Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, Burma and Russia) and from farther afield (South Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, Australia, North America and Europe).

The main areas that attract foreigners are the large urban areas along the coast (Guangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing) and borderland regions in the South, Northeast and Northwest, but smaller numbers are also found in smaller cities across China.

Foreign residents generate specific demands for education, housing and health care and are setting new patterns in entertainment, life-style trends and popular culture. Especially large or more visible groups like the Koreans and Africans are changing the cultural and political map of Chinese society. Coming to terms with new types of diversity has already started debates among Chinese public intellectuals that involve reconsiderations of culture, heritage, and ethnicity in the concept of the Chinese nation.

Both before and after 1949 China’s reception and treatment of diversity has not been predicated on ideas of shared rights. The aim was not to incorporate foreigners and other non-Chinese, but to insulate Chinese society from them. Currently, China embraces foreign residence as a means of joining globalization, yet still avoiding pressures for large-scale permanent settlement and full integration into society.

The new 2012 exit-entry law for the first time addressed the full package of exit, entry, settlement, immigration, expulsion, naturalization, refugee status, and trafficking, reforming two previous separate laws for foreigners and Chinese citi- zens which had been in place since 1994. This significant development highlights a growing recognition that immigrants are part of Chinese society.3

Foreign residence in China is fueled by rising demand for labor and skills.4 China has largely depleted its own (rural) surplus labor force, and labor-intensive sectors of the economy (agriculture, construction, export processing, care) increasingly turn to foreign workers to make up the difference.

The foreign population is important to the central and local governments because they possess skills, qualifications and foreign networks that are scarce in China. Government “talent programs”, providing high-level professionals and scientists with funding and other benefits, are the clearest expression of this, but actually account for only a fraction of the number of foreigners. The vast majority have arrived under their own steam, finding employment, starting businesses, or even marrying and having children.

In this MERICS Monitor, we will discuss the most salient issues confronting the Chinese government and foreign residents themselves. These include:

- the potential role of migration in alleviating the looming demographic crisis

- China’s recent shift to a more comprehensive, top-down approach to regulating foreign migration

- gaps in providing equal treatment for foreigners

- challenges of integrating resident foreigners

Such issues are also relevant to the governments and organizations from the foreigners’ countries of origin, and international organizations working in or with China on international migration, asylum, human smuggling and trafficking. More generally, the entry and employment of foreigners are also important for foreign and domestic companies and other employers with foreign employees in China.

2. China needs more migration as its population ages and its workforce shrinks

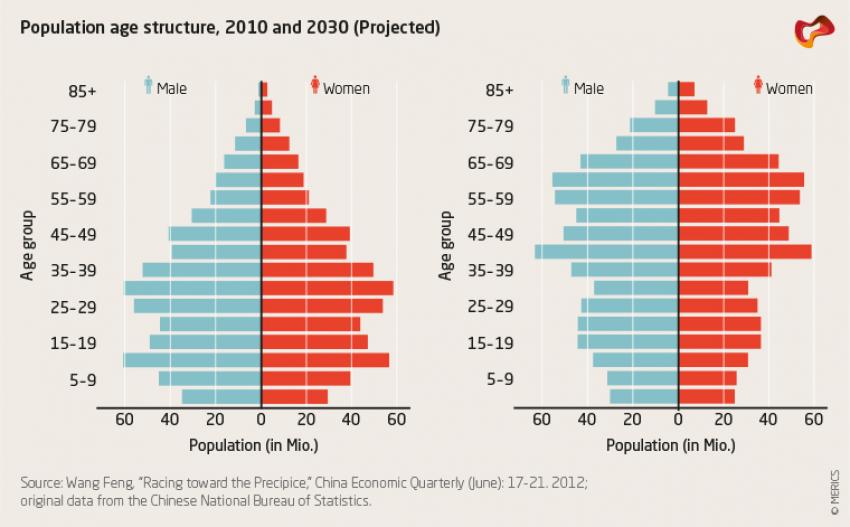

Massive and unprecedented demographic changes in China are having a profound impact. The rapidly shifting population age structure has already affected the Chinese and global economy, with China’s shrinking labor force driving up labor cost and altering the global supply chain. Since 2010, the number of people aged 60 and over increased by more than 30 per cent, while the number of people in the age group between 20 to 24 years old dropped by about 30 per cent. By 2030, the 60-plus population is expected to grow by a staggering 60 per cent to reach 390 million, accounting for one quarter of the total population (see exhibit 1). Yet even with continued increase in life expectancy, the decline in China’s population is expected to commence in as soon as in five years, certainly a historical turning point for China. So far, the Chinese government has mostly avoided foreign immigration as a policy solution for emerging labor shortages. Reasons for this include the country’s lack of a large-scale immigration tradition as well as its recent history of enforced family planning under the one-child policy.5 While this policy was relaxed in 2015, Chinese citizens are still not free to determine their family size. Both issues could trigger popular resistance against any large-scale government-orchestrated labor migration.

China’s migration needs are linked to demographic trends that are much more diverse than suggested by its policy framework mainly aimed at attracting highly-skilled talent. Low-skilled labor migration therefore largely stays under the radar. In southern China, labor shortages have prompted local governments to put in place temporary work-permit schemes for low-skilled workers from Southeast Asia. According to the Filipino government (although this has never been con- firmed by China), in April 2018 the Philippines and China signed an agreement that will allow 300,000 Filipinos and Filipinas to work in China, including 100,000 English-language teachers.

3. China adapts immigration policies to a growing number of foreigners

The development of exit-entry legislation has been cautious, a legacy of the early decades of the People’s Republic of China when international mobility was limited.6 Still, since the 1980s the Chinese state has gradually built up a wide array of laws, regulations and policies for dealing with international mobility. In the last ten years, an increasing emphasis on regulation, control and national security in addition to service of foreign residents has unfolded, culminating in the adoption of the new Exit-Entry Administration Law of 2012.

In the 1990s, the Chinese government began to realize that China needed skills, knowledge and expertise that foreigners possessed. In the early 2000s, this came to include the fact that some foreigners would reside long-term. Nevertheless, the regulations on permanent residence in 2004 were strictly applied and residence was mainly given to ethnic Chinese as part of the initiative to reverse China’s brain drain.7

One tool to align immigration to the strategic priorities of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the state is talent programs to support China’s push to become a scientific and technological leader.8 The Thousand Talents Program 9 and many others at the central and local levels have brought an estimated 7,000 researchers to China.10

In 2018, the US government became worried about the impact of these pro- grams and other forms of scientific collaboration with China, tasking the FBI and other agencies with investigations into the Chinese links of US-based researchers, particularly those with a Chinese background.11 This move may well be connected to the current trade conflict between the two countries, but it is nevertheless clear that the global competition for talent itself is becoming fiercer.

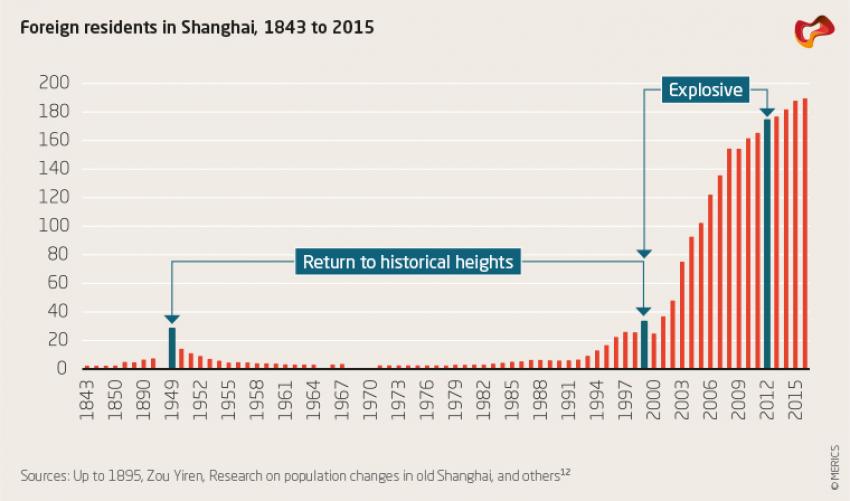

Case study: Immigration in Shanghai, China’s most global city

Since China joined the WTO in 2001, the number of foreigners registered living in Shanghai for six months and longer tripled to 176,363 in 2013, before dropping slightly to 163,363 in 2017. Including short-term foreign residents doubles that figure. The city’s share of foreigners constitutes about one percent of the population of 24 million (vs. about 0.07 percent nationwide), positioning Shanghai as an emerging global city. While foreign high-level professionals face increasing domestic competition, new gaps in Shanghai’s labor market, such as those for English-speaking maids, have emerged.

Shanghai hosts almost a quarter of China’s overall foreign working population. In recent years, the municipal authorities have been especially ambitious about attracting and retaining high-level foreign professionals. A new policy linking permanent residency to salary doubled the number of permanent residency holders from 2,404 in 2015 to 5,439 in 2017.

The city’s foreign population includes Japanese, American, Korean and French communities. However, an increasing share of foreigners living in Shanghai are now from other source countries. Between 2005 and 2015 the share from Japan and South Korea dropped from 44 to 31 per cent, while the share from “other” countries (a government category excluding Western countries) rose from 15 to 28 per cent.

3.1 Regulating foreigners' entry, residence and employment under Xi Jinping

Under President Xi Jinping, immigration reform has picked up some speed.13 China joined the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2016 and established its first national immigration agency in April 2018. A more comprehensive immigration policy field is forming, integrating and expanding policies in exit-entry management, diaspora outreach and talent plans.

The decision to establish a national immigration agency (Guojia yimin guanli ju 国家移民管理局, State Immigration Agency, SIA) is an example of the “top-level design” (dingceng sheji 顶 层 设 计 ) approach to policy making under Xi and an

expression of the government’s increasingly proactive attitude towards immigration, emphasizing both the need for better services for foreigners and strengthened border security.14

The idea that a more comprehensive approach to immigration is taking root: China has become an immigration country and needs the administrative tools to deal with that.15 However, stating publicly that China is becoming an immigration country still encounters widespread resistance: the Chinese public and administration still see the country as defined by its massive population.

3.2 Attracting Chinese foreigners

Foreign nationals of Chinese descent, both first-generation emigrants that have changed nationality and their descendants, make up a significant part of the foreign population in China. Xi has consistently emphasized the importance of over- seas Chinese as a key resource in advancing China’s position in the world.

In January 2018, the Ministry of Public Security announced that overseas Chinese may now qualify for a five-year multiple-entry visa or residence permit. The measure is part of a wider trend of recalibrating overseas Chinese policies. As the traditional overseas Chinese communities have been supplemented with new emigrants, students and transnational elites over the past decades, Chinese authorities are shifting the focus from historical diaspora communities to more recent immigrants and second and third generation overseas Chinese.16 Cooperation between overseas Chinese and talent-related bureaucracies and exit-entry authorities has increased as a result.

4. The rights of foreigners are constantly improved, but challenges remain

Overall, the legal framework of international migration to China has continued to improve since the adoption of the Exit and Entry Administration Law of 2012. Transparency regarding the different categories of entry and stay has increased. Application procedures have been streamlined and put online in order to improve the attractiveness of China as a migration destination, although at the same time visa applications have also become more complex and burdensome.

4.1 Visa categories of foreigners

Immigration law compartmentalizes foreigners in strict categories and hierarchies. The 2012 Exit and Entry Law defines specific visa, work permit and resident permit categories. A points-based work permit system specifies the usefulness of foreigners: A (high level talent, to be welcomed and attracted); B (skilled labor, to be retained), C (unskilled labor, to be restricted).17 The immigration regime, moreover, draws clear discrete lines between visa categories: if you came to work, then work on a working visa; if you came on a family visa, then sit at home and look after children; if you came to study, study and don’t work.

The implementation of a points system and the introduction of different categories of visa have contributed to more transparency. However, the clear distinction between A and B-category foreign nationals within the work permit system is not reflected in different legal resident statuses or other substantial benefits or privileges for A-category immigrants which would make China more attractive for highly skilled talent. The overall system of attracting highly skilled migrants would benefit from clear and predictable paths to acquiring a permanent residence status within a relatively short period of time.

4.2 Labor rights protection of foreign employee

Currently, work permits are granted for a specific job. Changes of employment or moving to a different region may require the issuing of a new work permit. The legislative framework that governs the employment relations between local employers and foreign employees is still based on the assumption that foreign employees do not need statutory protections of their labor rights as they are in a privileged position with high salaries and sufficient social security protection in their home countries upon return from China. As foreign employees often work in less privileged situations than before and stay in China for longer periods of time, this perception has become outdated.

So far, the PRC has not ratified the United Nations’ Convention on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers. According to Art. 25 (1) of the Convention, migrant workers shall enjoy treatment not less favorable than nationals in respect of remuneration and other conditions of work. Art. 25 (3) further requires that foreign employees not be deprived of these rights by reason of any irregularity in their stay or employment.

In practice such equal treatment is often not given. The Regulations of the Administration of Foreigners Working in China (revised in 2017) fails to state that foreign employees are entitled to all labor rights and protections of the current Chinese labor legislation. Art. 21 and 22 merely stipulate that the income of foreign employees shall not be lower than the local minimum wage and that nation- al laws apply to foreign employees regarding working hours, rest and vacation, work safety and hygiene as well as social security, but fails to include protection against unjustified dismissal.

Furthermore, the Supreme People’s Court stipulated in the Judicial Interpretation on Labor Disputes of 2013 that a formal employment relation is not to be recognized if the foreign employee does not hold a valid work permit. However, courts in certain regions of China have taken approaches in interpreting existing legislation and the Supreme People’s Court judicial interpretations more favorable to foreign employees.18 The overall situation is therefore characterized by inconsistent adjudication that puts foreign employees often in an insecure position.

4.3 Regulation of student migration

In recent years, Chinese universities were encouraged to take increasing numbers of foreign students as part of China’s efforts to build up soft power in other countries, especially those along the corridors of the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI).

Foreign students in university degree programs who are proficient in Chinese constitute a significant pool of potential high-skilled migrants. For a successful transfer of students from university to employment in China, internships play a crucial role. They help them to get familiar with the requirements of the labor market, enable them to practice their language skills and build a professional network. However, the legal requirements for internships are often difficult to meet, while universities are reluctant to assist students in obtaining approval. Despite a recent relaxation of previous restrictions, foreign students who graduate from a Chinese university continue to confront hurdles in finding employment or starting a business in China upon graduation and usually end up leaving the country.

4.4 Exit restriction

Art. 28 (2) of the PRC Exit-Entry Administration Law stipulates that foreign nationals can be required to stay in China if they are involved in an unsettled civil case. In general, measures that provide for such severe restrictions should adhere to the proportionality principle. Recent practice has conveyed the impression that foreign nationals can be subjected to exit restrictions at random, even if no laws were violated.19 This may contribute to a decline of the attractiveness of the PRC as a destination country for migrants.

Incidents like the arrest of Canadian citizens in retaliation for that of a Chinese Huawei executive in Canada have reminded many foreigners that the rule of the party trumps the rule of law. The Chinese government emphasizes the legal basis of the detentions, which highlights how important it is to fully adhere to Chinese law when living, working, studying or doing business in China.

5. Integration of foreigners is hampered by tightening national policy

While the Chinese government considers controlled, skilled immigration beneficial to China’s socio-economic development, it has long avoided formal statements on broader issues of migrant settlement and integration. In addition, a perception has emerged that not all aspects of immigration are necessarily beneficial, and gradually more attention has been paid to the problem of the “three illegals” (sanfei): illegal entry, illegal residence and illegal work. In addition, immigration is associated with security concerns like terrorism, subversive activities and international organized crime.

However, some things are gradually changing. The new State Immigration Administration (SIA) includes migrant integration in its remit. A planned Immigration Service Center, with offices throughout the country, will offer services to boost integration of “long-term foreign residents.20

Local governments in areas with concentrations of foreigners have been at the forefront of immigration policy development, promoting the idea of both serving and controlling foreigners. This is illustrated by our work in Guangdong province. Already by 2012, 106 foreigner management and service centers were established in ten cities across the Pearl River Delta region.21 These centers generally serve as service points for foreigners, but also assist local public security bureaus in regulating and managing foreign residents. Their approach, however, differs according to the category of foreigners they target.

With its focus on technology, innovation and the financial sector, the city of Shenzhen attracts high-end professionals from developed countries. The Shenzhen government has invested in communication with foreigners to facilitate legal and administrative provisions and foreigner service centers play a crucial role in this.

In the city of Guangzhou, the suppression of African residents in certain neighborhoods following repeated clashes around 2009 between the police and African traders that became an issue of “national attention.” 22 Africans from sub-Saharan countries were far from the largest foreign group in the city. However, their skin color made them “the most foreign of the foreign” 23 and sensationalized accounts of their number and activities in China spread widely. In response, local authorities introduced restrictive local regulations in 2011.24 Currently, foreigner management and service centers have mainly been tasked with facilitating control over foreigners and replacing migrants’ ethnic self- organization.

Even where the local government emphasizes service and communication the stronger national emphasis on management and control is rapidly gaining ground.25 In Keqiao, a city in Zhejiang with a substantial community of South Asia textile traders, the local foreign service center helped South Asian traders gain direct access to public services and vital information related to their visa and company registration. Since 2017, however, national policy priorities on policing and control have taken precedence, and the center no longer has the freedom to help and interact with the foreigners in the city.

In certain respects, the new emphasis on national coordination and standardization of foreigners’ policies is a good thing for foreigners in China. It promises a more uniform and predictable regulatory environment and clearer rights and duties. However, it also becomes more difficult to maintain the favorable policy environment in those places that seek to attract foreigners. Increased enforcement of residence and employment regulations intensifies the state of “permanent impermanence” 26 in which the system keeps foreigners. Despite increasing transparency, many find it hard to remain at the right side of the law and have trouble navigating the linguistic barriers of the regulatory framework.

6. Chinese perceptions of foreigners are changing

For several decades rapidly developing China was an exciting destination for foreigners aiming to explore new lifestyles or fast-track their business or careers. Many migrants were able to secure better positions and enjoyed enhanced social status based on their transnational skills or simply by virtue of being foreign. In China’s global cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou), a “Korea City” or “African Brooklyn” became a feature of the urban landscape. Yet immigrant groups do not have a structural position in the Chinese nation.

The government does not aim to make society more “diverse” or “inclusive” per se. As the society and economy have become richer, better educated and internationally connected, the position of foreigners is changing. Talk of “useless” foreigners or unnecessary competition on a job market already filled with Chinese graduates has increased. Non-white migrants can even face blatant discrimination in the labor market.

A growing body of research concludes that foreigners live segregated from Chinese society. Formal organizations representing immigrants are difficult to establish. However, informal networks where immigrants share information and other resources based on nationality, ethnicity, profession or interests are flourishing. They aim to improve life quality, but some also work on rights protection and raising awareness of immigration realities among the public.

Moreover, the public branding of African foreigners as the “three illegals”,27 of foreign English teachers as “white trash” or even “foreign spies”, and the questioning whether foreigners are able or even willing to adapt to Chinese culture makes many foreign migrants feel alienated and unwelcome. The Chinese government’s silence on these issues sanctions growing tendencies of public intolerance to racial, ethnic and cultural difference in China.28

A mismatch exists between such migrant experiences and the current policy framework with its narrow focus on management and top talent. The government focuses on making the lives of the latter group more convenient, for instance by giving out more green cards to top-earners, yet they remain hard to retain. China’s high salaries are attractive, but the country rates far below the global average for family wellbeing and quality of life. Many foreigners continue to be attracted to China, but on arrival find Chinese society less welcoming than they had hoped it to be.

Finally, the position of foreigners in China should also be examined against the light of larger geopolitical shifts. Immigration and immigrants are increasingly turned into a weapon in the contestation between China and the US. The most salient examples include the tight scrutiny imposed by the Trump government over Chinese scientists in the US and the Chinese government’s detaining Canadian citizens in China. These incidents are not about immigration per se – changes in migration management would not prevent these tensions – but they directly affect migrants’ life and their transnational connections. How to deal with the intricate attempts of politicizing migration in the time that migration itself is be- coming more complex poses new challenges to both to China and other nations.

7. Conclusions

Foreign immigration in China is becoming more diverse. While the number of high-earning expatriates from developed countries has peaked, China attracts more students than ever from all over the world, including many from lesser developed countries. Low-skilled labor and marriage migration are also on the rise. At present, immigration policy is driven by narrow concerns of regulation, institutionalization and control Immigration policy, and remains predicated on just the need for high-quality professionals, researchers, entrepreneurs and investors. Policy does not address long-term challenges, and especially not the emerging demographic transition. A vibrant and sustainable economy requires a labor force that is not all college-educated. Although at the central level a recognition is emerging that China has indeed become an immigration country, a more comprehensive approach to immigration is only found at the local level in areas with larger numbers of temporary or permanent foreigners.

The legislative framework that governs the employment relations between local employers and foreign employees is still based on the assumption that foreign employees do not need statutory protections of labor rights. As foreign employees often work in less privileged situations than before and stay in China for longer periods of time, this framework appears to have become inappropriate.

Policy does not deal with immigrants as people. It neither emphasizes aspects of integration of foreigners into society nor does it provide clear and predictable paths to acquiring permanent residence. A more fundamental approach to social inclusion of foreign residents is indispensable for social harmony. Immi- gration policy is not yet driven by the much broader realization that this will make China a much more diverse society with new categories of people and ethnic, national, racial and religious communities that need to be incorporated into the fabric of political and social life. Even a city like Shanghai has a long way to go to catch up with first tier global cities, especially in the areas of ease of doing business, information exchange, and cultural assets.

Finally, fighting conflicts with other nations and powers at the expense of foreign residents of China will not only undermine foreigners’ commitment to and faith in a life in China, but will also fatally wound China’s ambitions to become a globalized economy and society, a world leader and future superpower.

- Endnotes

-

1 | This paper discusses the main findings and policy issues arising from the projects of the 2014 – 2019 research program on Immigration and the Transformation of Chinese Society funded under the Europe-China 2013 Call. The project research teams were based at the ES- SCA School of Management, Angers, France; Cologne University, Germany; Fudan University, China; Leiden University, the Netherlands; the University of Manchester, United Kingdom; and the University of Oxford, United Kingdom. For more information, see the project website: https://immigrantchina.net. In addition to the authors of this MERICS Monitor, the researchers whose work has fed into this report include Lai Pik CHAN (Cologne); Ka Kin CHEUK (Leiden); Lin Goedhals (ESSCA); Jasper Habicht (Cologne); Eva RICHTER (Cologne); Andrea STRELCOVA (ESSCA); Yong CAI (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill); SHEN Jie (Fudan); SHEN Ke (Fudan); ZHU Qin (Fudan).

2 | “2018 nian quanguo bianjian jiguan jiancha churujing ren yuan shouci po 6 yirenci” (Nationwide border authorities for the first time complete over 600 million border checks in 2018), Ministry of Public Security, January 9, 2019,http://www.mps.gov.cn/n2254996/n2254999/c6342840/content.html. Accessed: June 14, 2019.

3 | Guobin Zhu and Rohan Price, “Chinese Immigration Law and Policy: A Case of ‘Change Your Direction or End Up Where You are Heading’?”, Columbia Journal of Asian Law 26(1), 2013, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2088683 Accessed: September 22, 2019.

4 | Albert Park, Cai Fang and Du Yang, “Can China Meet Its Employment Challenges?”, in Growing Pains: Tensions and Opportunity in China’s Transformation, edited by Jean Oi, Scott Rozelle and Xueguang Zhou, Stanford: Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center, 27-55, 2010.

5 | Wang Feng and Yong Cai, “China Isn’t Having Enough Babies”, Op-ed, The New York Times February 26, 2019.

6 | Anne-Mary Brady, Making the Foreign Serve China: Managing Foreigners in the People‘s Republic. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

7 | Parts of this paragraph have been paraphrased from Frank N. Pieke, “Immigrant China”, Mod- ern China 38 (1): 40-77, 2012.

8 | See Max J. Zenglein and Anna Holzmann, Evolving Made in China 2025 China’s Industrial, Policy in the Quest for Global Tech Leadership, Berlin: MERICS, 2019. | http://www.1000plan.org/en/. Accessed: September 22, 2019.

9 | Ingrid d’Hooghe, Annemarie Montulet, Marijn de Wolff and Frank N. Pieke, Assessing Europe-China Collaboration in Higher Education and Research, Leiden: Leiden Asia Centre, 2018; Cong Cao, Jeroen Baas, Caroline S. Wagner and Koen Jonkers, “Returning Scientists and the Emergence of China’s Science System”, 2019, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3395899. Accessed: September 4, 2019.

10 | See Jeffrey Mervis, “NIH probe of foreign ties has led to undisclosed firings – and refunds from institutions”, Science June 26, 2019, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/06/nih- probe-foreign-ties-has-led-undisclosed-firings-and-refunds-institutions. Accessed: September 3, 2019.

11 | See exhibit 2: up to 1895, Zou Yiren, Jiu Shanghai renkou bianqiande yanjiu (Research on population changes in old Shanghai), Appendix, Table 46, p. 145; post-1949 to 2000, He Yaping, Shanghai guojihua renkou yanjiu (Research on the internationalization of the pop- ulation of Shanghai), Tables 4-6, p. 88; post-2000, Shanghai Statistics Bureau; post-2013, estimates based on total foreign residents and the average share of those who stay over six months between 2010 and 2013 (about 50 %).

12 | This section draws on Tabitha Speelman, “The National Immigration Administration and the Future of China’s Immigration Reforms”, unpublished paper, 2019. An early version of this paper was presented at ‘Chinese Global Engagement Abroad: Changing Social, Economic, and Political Configurations’ (5-6 July 2019), Hong Kong University of Science and Technology & The French Centre for Research on Contemporary China.

13 | “Wang Yong: Zujian guojia yimin guanliju” [Wang Yong: establishing the State Immi- gration Administration], March 13, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2018l-h/201803/13/c_137035628.htm. Accessed: June 14, 2019.

14 | Liu Guofu and Weng Li, “Quanqiu yimin qiyue de zhongyao linian, zhuyao tedian ji qi dui Zhongguo de qishi (Global compact for migration: key concepts, main features and implica- tions for China), Huaqiao Huaren lishi yanjiu 1: 1-8, 2019.

15 | Hong Liu and Els Van Dongen, “China’s Diaspora Policies as a New Mode of Transnational Governance”, Journal of Contemporary China 25: 102, 805-821, 2016.

16 | Liu, Guofu and Björn Ahl, “Recent Reform of the Chinese Employment-Stream Migration Law Regime”, China and WTO Review 4: 215-243, 2018.

17 | For example, Guiding Opinions of the Zhejiang Labor Arbitration Committee on Several Issues concerning Labor Disputes (2009); Summary of the Guangzhou City Intermediate People’s Court Seminar on Several Issues concerning the Trial of Labor Disputes (2008); Guiding Opinions of Shenzhen City Intermediate People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Trial of Labor Disputes (for Trial Implementation) (2015).

18 | Jasper Habicht, “Exit Restrictions in the Context of Chinese Civil Litigation”, Asia Pacific Law Review, DOI: 10.1080/10192557.2019.1651486, 2019. Accessed: September 25, 2019.

19 | “Guojia yimin guanliju qidong yimin shiwu fuwu zhongxin choujian gongzuo” (SIA starts preparation work for immigration affairs service center), Xinhua, January 24, 2019, http:// www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2019-01/24/c_1124038981.htm. Accessed: September 12 2019.

20 | Wang Pan, 10 ge chengshi 106 ge waiguoren fuwuzhan (106 service stations for foreigners in 10 cities), Guoji xianqu daobao, May 25, 2012, http://ihl.cankaoxiaoxi. com/2012/0525/41775.shtml. Accessed: September 29, 2019.

21 | Li Minghuan, Guoji yimin zhengce yanjiu (International immigration policy research), Xiamen University Press, 2011, 322. | Gordon Mathews, “Africans in Guangzhou,” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 44(4): 7–15, 2015.

22 | Heidi Østbø Haugen, “Residence Registration in China’s Immigration Control: Africans in Guangzhou”, in Destination China: Immigration to China in the Post-Reform Era, edited by Angela Lehmann and Pauline Leonard. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 45-64, 2018.

23 | Ding Feiping, Lou Pengying and Xu Li, “Zhongwai yimin guanli tizhi bijiao yanjiu (Comparative immigration management system research), Shanghai gong’an gaodeng zhuanke xuexiao xuebao 29(1): 5-11, 2019.

24 | Angela Lehmann, Transnational Lives in China: Expatriates in a Globalizing City, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

25 | This a play on the word fei that means both “African” and “three” in Chinese.

26 | Shanshan Lan, Mapping the New African Diaspora in China, Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.