Whispering advice, roaring praises: The role of Chinese think tanks under Xi Jinping

This analysis was produced with support from the Robert Bosch Stiftung. Robert Bosch Stiftung has been working and cooperating with think tanks globally in different contexts and various constellations for decades. To analyze the Chinese think tank landscape and to explore and map current framework conditions, the Robert Bosch Stiftung has therefore commissioned this report.

Click here for more information on MERICS standards to maintain independence in research and editing.

Key findings

-

More than 1,900 think tanks are active in China contributing to policy deliberation and promotion, they are key to party-state policy making and communication.

-

The Xi Jinping administration has, for almost a decade now, been pushing to closer align think tank’ activities with political agendas. “Think tanks with Chinese characteristics” are expected to maximize their research utility for the party-state.

-

There are several types of think tanks that fill different positions within the Chinese system, from full party-state integration to less political affiliations. Most of them are public organizations, integrated within party and state institutions.

-

Due to the changing policy environment under Xi Jinping, room for truly independent think tanks has become negligible, and even private think tanks are under political supervision. They are struggling to navigate a quickly closing space for critical debates.

-

This development affects foreign actors, also in Europe: Chinese think tanks are internationalizing, engaging with global policy debates abroad. Party-state proximity means they often become authoritarian narrators, taking Beijing’s messages to non-state fora or to track 1.5 exchanges with foreign officials.

-

Intensifying political oversight at home means that think tankers are constrained by Beijing’s propaganda red lines putting Chinese intellectuals and researchers in a tough spot. They are tasked to exert more influence; at the same time, they are being limited by growing narrative rigidity and red tape when engaging partners abroad.

-

Think tanks that proactively support government positions increasingly dominate the space, also in track 1.5 and 2.0 fora.

-

On the other hand, direct lines of communication with Chinese think tanks allow for more exchanges outside of official diplomatic channels, which is helpful to keep conversations going even at times of conflict. These channels have been revitalized after disruptions created by the Covid-19 pandemic and China’s Zero-Covid policies.

-

Nevertheless, to enable an informed and strategically viable exchange, foreign interlocutors must be aware of their Chinese partners’ political mission and current official objectives and talking points that come with their affiliation to party-state institutions.

1. Introduction

The latest Global Go To Think Tank Report (2021)1 identifies a worldwide total of 11,175 think tanks, suggesting that China-based organizations make up nearly 17 percent of them. The China Think Tank Directory 2022 (中国智库名录) lists 1,928 active ones.2 However, numbers are not everything. More important is to understand the regulatory conditions and degree of political integration that China’s think tanks operate under in order to assess their value as interlocutors and the context shaping their research.

Think tanks play an increasingly important role in official policy formulation. The output of official think tanks contributes to party-state deliberations on domestic and global policy issues.

Equally significant is the role of think thanks in communicating policy. The CCP leadership has an intense focus on controlling political debate at home, which is now matched by determination to build “discourse power” abroad, meaning China’s capacity to set the norms, topics and language of the international debates.

The think tanks also play an important role as a channel for unofficial exchanges with foreign partners. For instance, before the pandemic, a delegation of Chinese think tankers would visit Brussels for exchanges around every two months. After the pandemic, similar exchanges have resumed with visits from representatives of the Center for China and Globalization, the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, the China Institute of International Studies or the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Even in the narrowing discursive conditions that China’s think tanks operate under, engaging with them can grant important insights and contact, provided the European partners enter the conversations clear-eyed about the status of Chinese think tanks in China’s system. Open discussion with party-state officials has become rarer and more constraint, but the end of the Covid pandemic has restored people-to-people and track 1.5 and 2 exchanges. They are now firmly back on the agenda.

As Chinese think tanks are increasingly seeking outreach and partnerships with foreign counterparts, government structures and universities, it has become more important to understand their roles in official and unofficial political communication, especially for their foreign partners. Uninformed engagement creates risks of being unconsciously affected by Beijing’s messaging.

This report explains the regulatory requirements Beijing places on think tanks, then presents four case studies to illustrate the different types of think tanks and the roles they play. Finally, it analyzes recent international communication by prominent think tanks to consider how the party state’s regulatory regime sets the parameters for think tanks’ overseas activities.

Chinese think tanks emerged during the reform and opening up of the 1980s as participants in debates on political and economic reform, social development and technological modernization. They serve as brains trusts for policy-related research and are plugged into policy-making processes. More recently, they have become active exponents of Chinese views and solutions on global issues.

Since 2013, Beijing has aimed to align think tanks more tightly with the party-state’s political program and discourse. It has called for active support for official policies, while tightening regulatory restrictions on organizational independence and critical debate. In the same period, think tanks have become increasingly active exponents of Chinese views and solutions on global issues, a role that is once again evident as international exchanges are picking up after the pandemic.

The majority of Chinese think tanks are public bodies, organizations of the party state apparatus, serving as research and policy-advice units for the government, or research centers in public universities. Affiliated to public organizations, they operate under administrative and political supervision, though the degree of direct control and research guidance varies. While European and US think tanks often have ideological and financial links to political actors, they exist in a pluralist context. China’s restrictive regulatory regime means independent and critical policy research and open debate is next to impossible. Even private think tanks must navigate heavily controlled and politicized public debates within strict red lines, and regulation that incentivizes certain activities and research priorities as defined by the party state.

1.1 The main kinds of Chinese think tanks

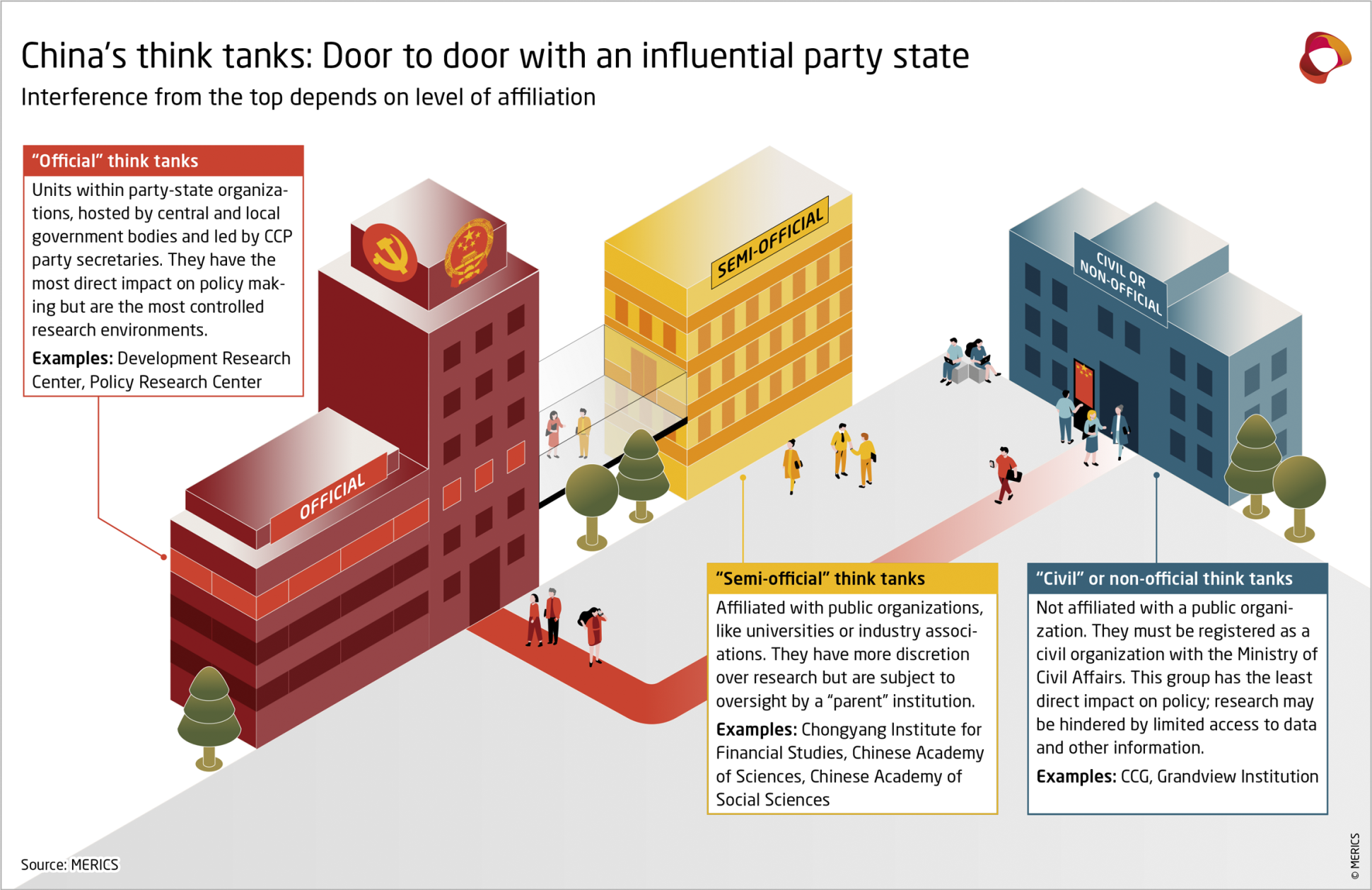

Understanding a think tank’s legal and ownership status, especially its degree of affiliation with formal party-state institutions helps to understand its organizational mission and/or limitations. Below, we identify three types of think tanks classified by their level of public- administrative affiliation.3

1) “Official” think tanks are units within party-state organizations, hosted by central and local government bodies. Part of the formal bureaucracy and civil service or cadre systems, they are led by CCP party secretaries who hold formal bureaucratic rank. These think tanks have the most direct impact on policy and decision making but are the most controlled research environments. A significant degree of critical and open discussion may exist within them for internal purpose, which only elites are privy to.

Top levels examples include the State Council’s Development Research Center (DRC) and the Policy Research Center which serves the Central Party Committee. Ministries and local governments also host their own think tanks.

As party cadres, think tank leaders may be rotated between jobs. For instance, Yin Hejun, former deputy party secretary of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), was promoted to Minister of Science and Technology4, while Bi Jingquan retired as party secretary at the national market regulator to lead the China Centre for International Economic Exchange5. Switching from political office to think tank leadership is not uncommon among retiring officials who can deploy their networks and insight to advance public causes.6

2) “Semi-official” think tanks are affiliated with public organizations, such as universities or industry associations. They have more discretion over their research and activities but are subject to oversight by their ‘parent’ institution. One example is the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies (RDCY), hosted and partially staffed by Renmin University though largely privately funded. Renmin University’s party committee supervises RDCY7, probably with little impact on daily management or research topics. Yet, it has the power to veto activities and initiate party disciplinary measures.

Another example are CAS and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), often called China’s largest think tanks. These public research bodies are more akin to entire universities and affiliated to the State Council. Their size, scope, and academic nature gives their researchers a wider remit and more scope for work on political issues than in most other organizations making them the leading research arms of the party state.

3) “Civil” or non-official think tanks are not affiliated with a public organization and must be registered as a civil organization with the Ministry of Civil Affairs.8 Lacking institutional funding or a public service payroll, many engage in some commercial activities and fundraising. Think tanks in this group cover many topics but have the least direct impact on policy and their research may be hindered by limited access to data and other forms of information.

1.2 A decade of tightening regulation

Beijing began to establish modern think tanks such as the DRC in the 1980s, mainly for governmental in-house policy research. From the mid-1990s onwards the think tank field grew and diversified, as private and commercial forms of organization gradually liberalized. Privately funded and commercial think tanks were launched, as were hundreds of university-based research centers, and think tanks affiliated to ministries.9 A number of independent think tanks were established as centers for research and public debate. For instance, the Unirule Institute of Economics10, was founded by five economics professors in 1993.11 Dedicated to market reforms, it regularly ranked as influential in the annual “Go To” report published by the University of Pennsylvania.12

The more restrictive political approach pursued by Xi Jinping began to encroach on non- public organizations from 2013 onwards. The CCP’s infamous Document Number 9 took aim in 2012 at seven “unacceptable evils”, including “Western notions of civil society” and the “free flow of information on the internet”, that it cited as tools of “anti-China forces” to “dismantle the ruling party’s foundation”.13 A sweeping policy shift towards all independent organizations, critical research, media and public discourse shrank the space for policy debates and research and was quickly felt in non-official think tanks. Unirule was forced to shut down in 2019, wiping out one of China’s best known and well-regarded think tanks.

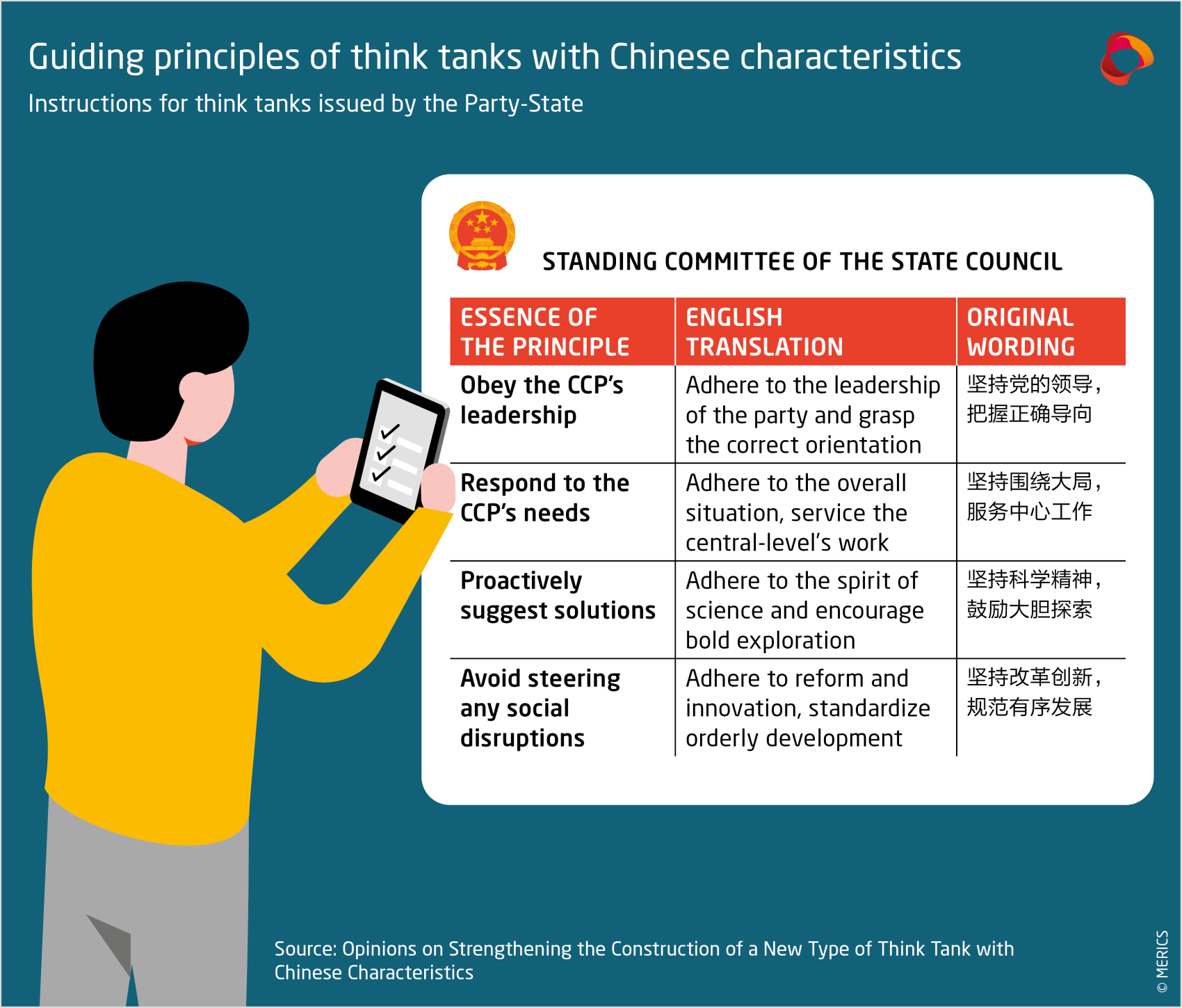

From 2013 onwards, China’s leaders called for “think tank with Chinese characteristics” that took “following the party” as a basic principle. Today, official party-state narratives and priorities dominate the field.

1.3 Think tanks with Chinese characteristics: the party-state’s intellectual back office and message amplifiers

Xi’s initiative to establish “think tanks with Chinese characteristics” is intended to create and guide research and exchange platforms for official party-state objectives. Xi described their creation as “a major and urgent task” in 2014. The concept took full shape in the January 2015 document “Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of a New Type of Think Tank with Chinese Characteristics”, issued by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council. The objective: to develop an advisory system readily accessible to party-state actors (加强中国特色新型智库建设,建立健全决策咨询制度).

These think tanks are not mere executors of the party’s will, deprived of agency, nor autonomous agents. Also, many of the current leading think tank and public intellectual figures in China have been educated abroad in environments of intellectual openness. Still, they operate within a permitted degree of autonomy, based on service to the party-state’s goals. The Central Committee’s General Office has defined them as non-profit research and consulting institutions that “serve the party and government in scientific, democratic and legal decision-making” (服务党和政府科学民主依法决策为宗旨的非营利性研究咨询机构).

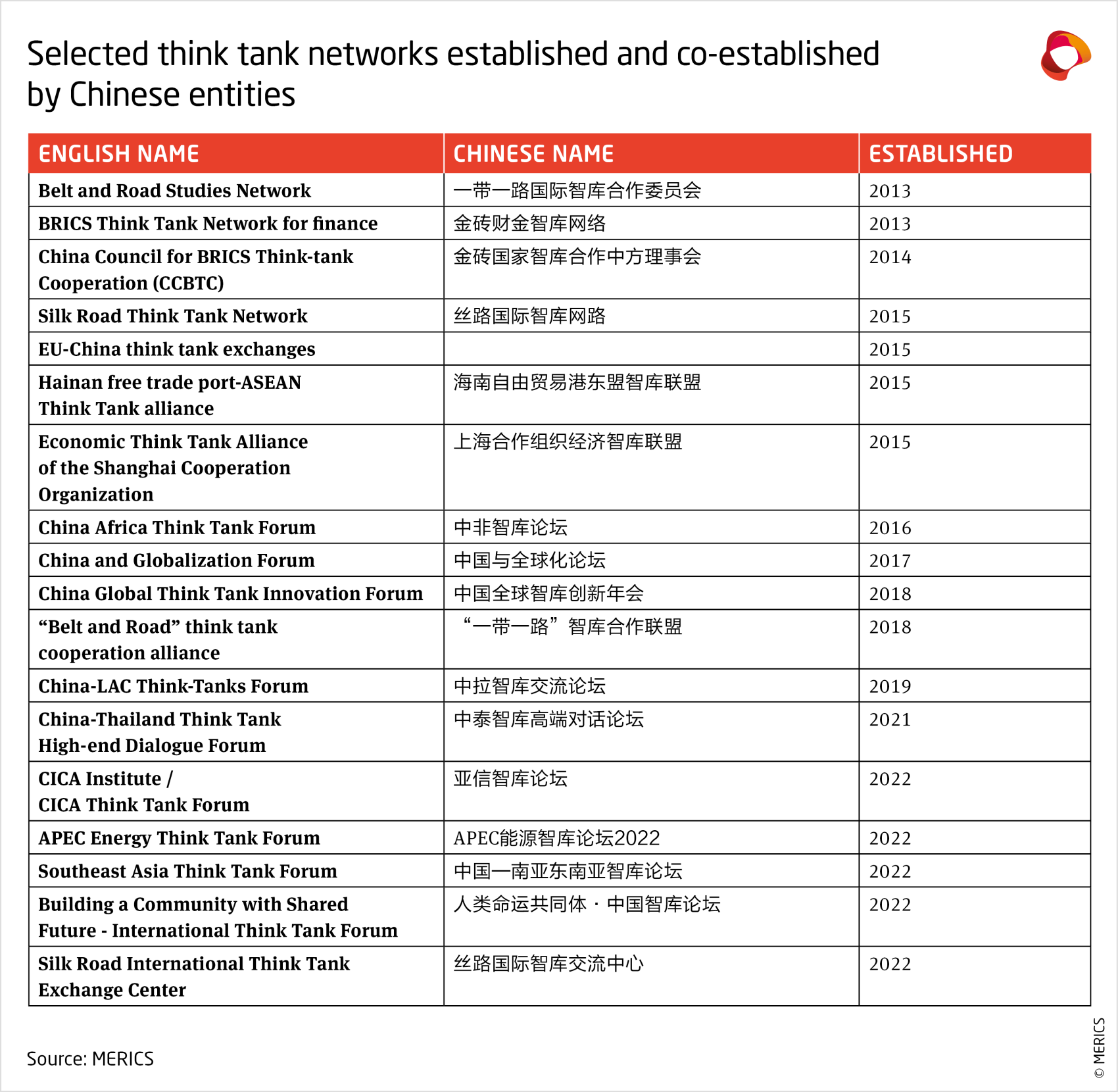

This dynamic is visible in how they are increasingly pushed to revert to official talking points in their outward facing messaging, something the Chinese think tank community itself voices discontent about.14 The outward push also relates to establishing new networks. For instance, Xi told the Second Belt and Road Forum in 2019 that China would “establish an international co-operation council for Belt and Road think tanks”, listing this project alongside media liaison and other communications work.

Regulators limit the scope for non-governmental “civil” think tanks to engage in independent, critical research and activities. They must register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs and submit to a “dual responsibility management system”, introduced in 2017. Either the Federation of Social Science, or a government unit (e.g., ministry or local department dealing with relevant policy) is charged with reviewing the think tank’s activities, “ideological and political work, party building, personnel management, seminar activities, foreign exchanges” etc.15 Losing sponsorship can end the think tank’s legal registration.

1.4 Inward-facing roles: Advice and feedback

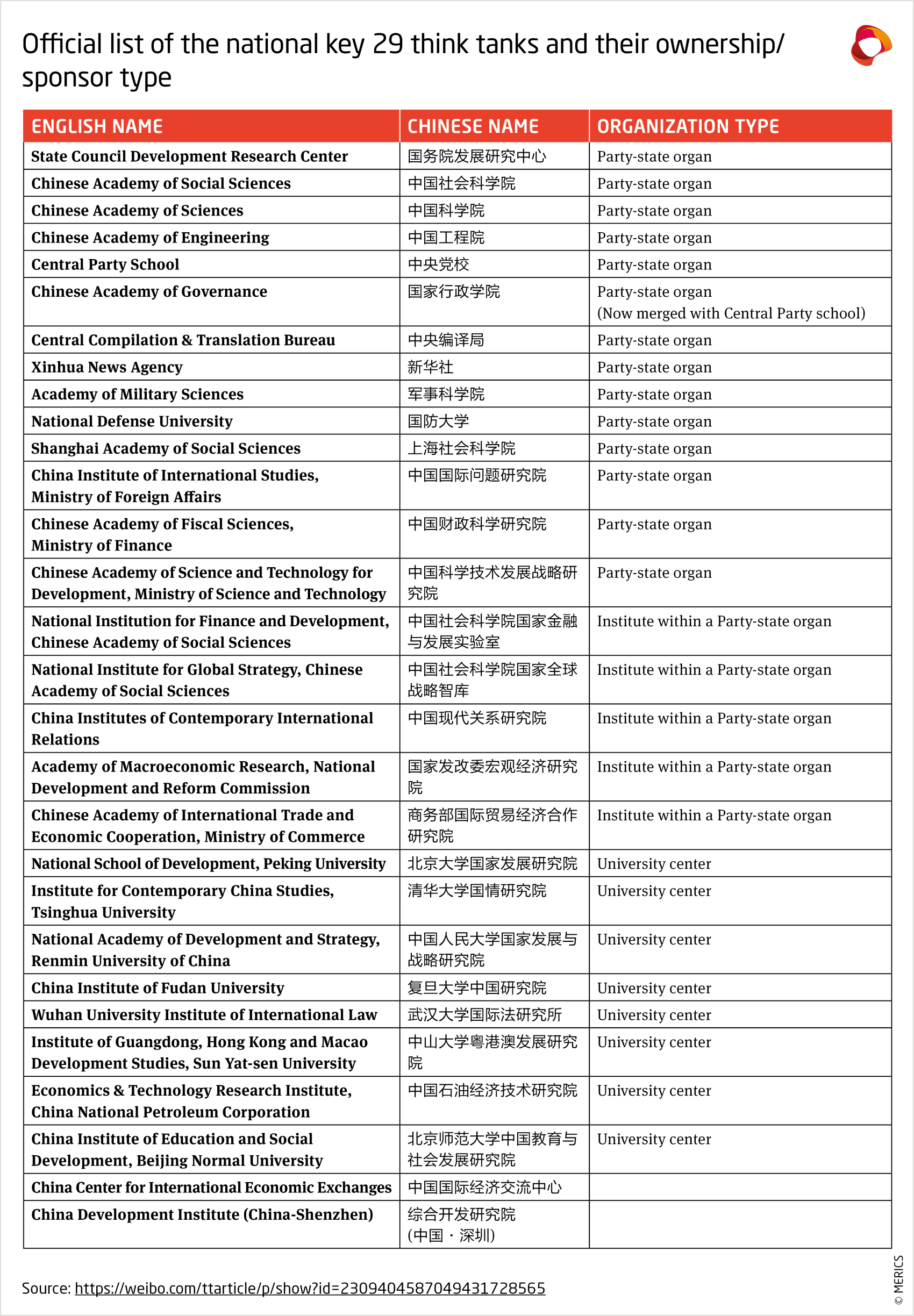

The CCP Central Committee’s target was to approve between 50-100 new “national high- end think tanks” (国家高端智库) officially elevating them into special advisors to the party state. Publicly available information states that 29 think tanks have made the cut, all of them official think tanks, public universities, or their affiliated research institutes. These new national high-end think tanks are linked to the Central Publicity Department (formerly the Central Propaganda Department) and their work can be transmitted to the top party- state leadership.

Xi told the 20th Congress of CAS in 2021 that its scientists should “actively provide council” and “support national decision making”. One mechanism through which this can happen, is the pishi (批示) system. Here, officials can inject requests to think tanks, with funding opportunities for execution attached. Pishi usually means leaders providing written comments on reports or documents. It is used to specify requirements, give guidance, or make decisions on reports or plans submitted by think tanks, and enables leaders to request specific research topics from official and semi-official think tanks. This creates a feedback loop and deepens the integration of think tanks in policy-making processes. Party-state leaders can for instance request a study on urban transportation, or ask for inputs to speech-writing and background information, including when meeting foreign interlocutors.

For instance, Hu Angang,16 Director of the Institute for Contemporary China Studies at Tsinghua University, has been explaining to top leadership the key reports from the United Nations or the World Bank, interpreting their relevance for China. Under the pishi system, points that capture interest of the leaders are marked with their signatures, as some of Hu’s work is said to have received such approval from then Premier Li Keqiang. Although not visible externally, the pishi system created an additional system of assessing the relevance and influence of think tanks and universities, making them compete for leaders attention.17

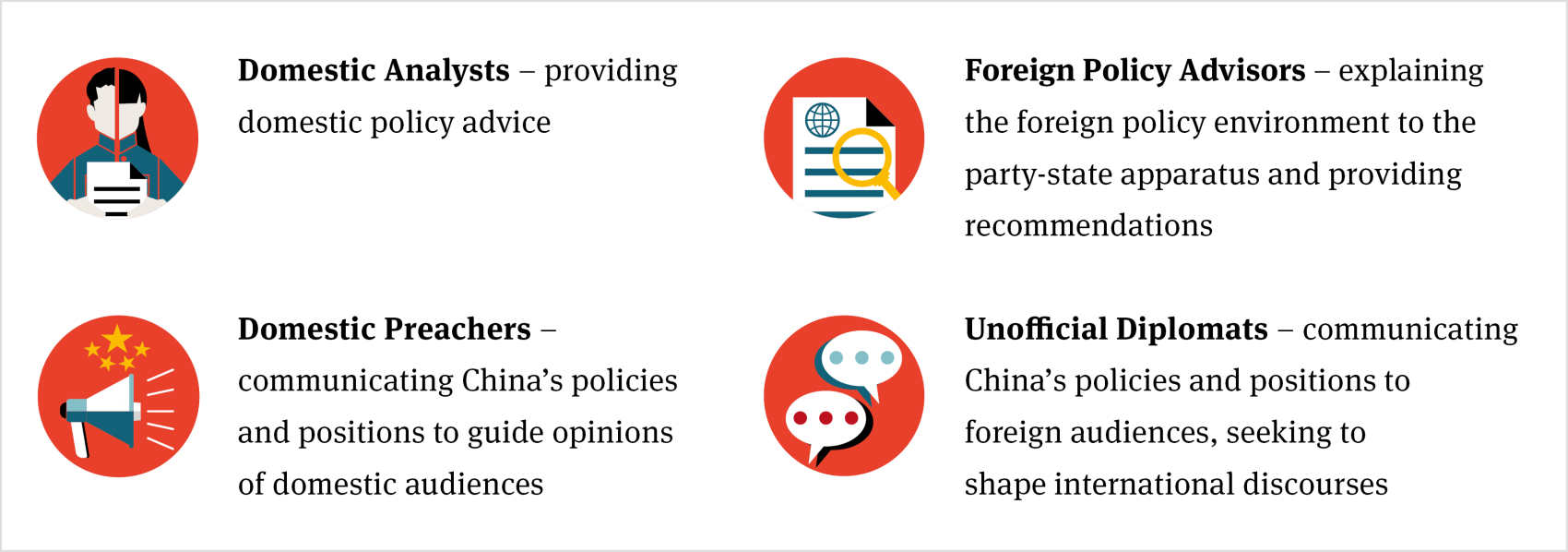

1.5 Outward-facing roles: Opinion guidance and international communication

These newly elevated think tanks are also expected to amplify party-state messaging. In domestic mass media, their contributions should “explain the party’s theory, interpretate public policy, […] guide social hotspots, channeling the public mood to positive effect” and “spread mainstream ideological values and gather positive social energy (阐释党的理论、解读公共政策、[…] 疏导公众情绪的积极作用) and “传播主流思想价值,集聚社会正能量”).18

Externally, they are tasked with “making Chinese voices heard on the international stage” through establishment of dedicated think tank networks and promoting viewpoints aligned with that of Beijing in the media and in exchanges with foreign elites to “enhance China's international influence and international discourse.” Outward facing messages must align with Beijing’s official talking points – including in track 1.5 and track 2 exchanges. Work to develop networks with foreign counterparts must ultimately serve to amplify Beijing’s desired messages.

1.6 Centralized and coordinated diplomacy: how think tanks should “tell China’s story well”

Since 2013, two foreign policy trends have reshaped the environment for China’s international relations-oriented think tanks. First, Xi’s administration has centralized the foreign policy and diplomatic apparatus. Second, more kinds of actors are being pulled into executing Beijing’s foreign policy agenda. Xi has called on all Chinese actors to “tell China’s story well” (讲好中国故事) to strengthen China’s international discourse power (国际话语权).

Changes to the foreign policy apparatus stem from the concept of “greater diplomacy” (大外交), or incorporating more Chinese actors into foreign policy activities. The Central Foreign Affairs Commission (CFAC) is the central unit sending coordinating instructions that trickle down the system, among others to think tanks. Those that are closely linked to the CFAC therefore deserve particular attention, as they are well placed to be intermediaries conveying narratives in and out of the Chinese system.

Beijing’s greater centralization and control means the regulatory environment favors official and semi-official think tanks aligned to party-state actors. Still, think tanks serve different organizational missions, and have varied roles within this straightened environment.

2. Think tanks with Chinese characteristics have a political mission

China’s think tank landscape remains diverse, though a clustering trend is observable. Think tanks increasingly converge around four broad archetypes (see below). The case studies deal with well-known and representative think tanks corresponding to each archetype and include some of the most internationally well-known and active official and semi-official think tanks.

Case studies

Domestic analysts: State Council Development Research Center (DRC)

Main tasks

- Conduct and coordinate strategic research on China’s socio-economic development. Provide research-based policy advice to the State Council and party decision makers.

- Research for China’s medium- to long-term development strategies in fiscal, economic, industrial and social areas, including input to macro development plans (e.g., Five-Year Plans).

- Coordinate international cooperation on development research and policy.

- Fulfill policy review and research tasks on specific issues ordered by policy makers.

Key facts

- Established in 1985 as a unit under the State Council by merging several research centers on socio-economic development.

- The main policy advice organization within the state apparatus.

- Its seven sectoral departments, 11 research institutes, and in-house publishing house provide Chinese leaders with rich policy research on domestic development issues.

- Together with CAS(S), it is one of the most important partners for international research collaboration on Chinese development.

Overview

The DRC is one of China’s most prolific policy research institutions. It is the State Council’s own policy research and advisory center, focused on macro-economics and industrial and social development issues. Many of its former experts and leaders are well known scholars and officials, such as its founding Director Ma Hong, the prominent economist Wu Jinglian, and former Vice Premier Liu He.

The DRC has long-standing research collaborations with the World Bank and other international organizations, and its reports are generally respected for their thorough research as they are less ideologically infused than, e.g., party think tanks. It is a key source for technocratic and market-oriented policy research and advice on domestic industrial and social development. Reporting directly to the State Council and tasked with drafting strategic development policy, it enjoys access to data and decision makers, and few other think tanks can match its policy impact.

Domestic preachers: The Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University (RDCY)

Main tasks

- Set up in 2013 with a grant from Shanghai Chongyang Investment Group as a collaboration-oriented think tank at Renmin University, Beijing.

-

Aims to leverage its expert community for policy research and serve as an international platform on China issues.

Key facts

-

Its pool of ca. 80 affiliates includes leading experts from Chinese government and research institutions and foreign visiting fellows.

-

It hosts several dozen events annually and publishes frequent commentaries and reports. Its experts frequently appear in public media discussing global economic and political affairs.

-

Its focus topics have recently shifted from Belt and Road Intiative and development issues towards global governance, eco-finance, global tensions and US-China relations.

-

It has a large domestic media footprint and its leading experts comment in major foreign media.

-

Executive Dean Wang Wen was a Global Times columnist till 2022. He supports nationalist views and argues for a better understanding of Russia in his analyses.

Overview

RDCY, as it is known, is among China’s best-known think tanks. Although it is a semi-official organization within Renmin University (or ‘Ren Da’), its founding bequest came from private fund management company Shanghai Chongyang.19 RDCY has established itself as a forum for Chinese and international experts on global financial and economic issues. With its growing pool of fellows, busy events schedule and written output, it is a regular on the Go To Think Tanks Index of the top 145 non-US think tanks worldwide (it was ranked at 118 in 2019).

After some reorganization in 2017, its outward-facing programs are: global governance; eco-finance; the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); major power relations. As a venue for conferences and events, jointly with other large Chinese institutions, it serves as a platform to communicate Chinese views on global affairs. Its strategy and influence were on show at its symposium on the 10th Anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative, jointly hosted with Renmin University, the Chinese Foreign Language Press (part of the CCP’s propaganda arm), the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs (a vice-ministerial organ for foreign relations), and the Nizami Ganjavi International Center of Azerbaijan. Speakers included ex-heads of state from Serbia, Bosnia Herzegovina, and Kyrgyzstan.

Such events show how RDCY works as an effective networking and communication hub for foreign guests and Chinese interlocutors. Dean Wang Wen is known for hawkish positions and favoring a more muscular Chinese stance in global affairs. A former advisor to several ministries, he has briefed Xi and senior officials.

Foreign policy advisors: China Institute of International Studies (CIIS)20

Main tasks

- Provides direct input to ministries linked with foreign affairs.

- Elaborates on China’s foreign policy theory – including Xi Jinping Thought on diplomacy and foreign affairs.

- Provides space for senior officials’ publications.

- Serves as a convening platform for Chinese foreign policy officials.

Key facts

- Established in 1956 (as CAS’s Institute of International Relations) as the first research institute on foreign affairs in China.

- CIIS is directly administered by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and its leadership recruited from among former ambassadors.

- Around 200 employees organized within eight research departments.

- One of the 29 “national high-level think tanks” since 2020, it hosts the Research Center for Xi Jinping Thought on Foreign Affairs.

Overview

CIIS represents a type of think tank deeply enmeshed within the Chinese party-state system; it was created in the early years of China’s foreign service. Its eight departments partly overlap with the Ministry of Foreign Affair’s own regional structure (US, Asia-Pacific, Europe, Developing countries etc.) supplemented by International and Strategic Studies and World Economy and Development.

Much of CIIS’ research activity remains outside public view as it is the MFA’s in-house think tank. Its flagship publication is China International Studies, a bimonthly journal aggregating high-profile policy analysis. It publishes the (almost annual) CIIS Blue Book on the International Situation and China's Foreign Affairs, which assesses the international landscape and China’s position in it. CIIS places commentaries and academic articles by its experts. But since 2018, its public facing report series has become more limited –exceptions include a Covid-19 focused report series released in 2020. External communication is not CIIS’ primary objective: the English language translations and website materials lag behind the Mandarin originals by years.

CIIS caters to the MFA’s interests by providing internal research and a platform for senior party state foreign policy officials to promote foreign policy concepts. For instance, in 2022, Wang Yi (in his capacity as Minister of Foreign Affairs and later as director of the Office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission) contributed to half the issues released that year. In July 2020, CIIS partnered with the MFA to open a center for Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy Studies (习近平外交思想研究中心), a move that elevates its ability to participate in translating ideological positions into the foreign policy agenda ideas.

Unofficial diplomats: Center for China and Globalization (CCG)

Main tasks:

- Communicate and promote Beijing’s official narratives abroad.

- Gauge partners’ views on Beijing’s policies and test responses to foreign policy ideas. Identify commonalities of interests with China’s agenda.

- Serve as an intermediary between the party-state and foreign counterparts by acting as a more flexible interlocutor.

Key facts:

- Established in 2008 with headquarters in Beijing. Private, without official governmental affiliation.

- Operations focus on outreach rather than research.

- Possible links* to the United Front Work Department and CCP International Liaison Department.

Overview:

Self-described as “China’s largest independent think tank”, the CCG is very active in convening activities and track 1.5 and track 2 diplomacy, often gaining privileged access to European officials.

It cultivates an image as a think tank well-connected within the Chinese system, but independent from the party state. CCG presents itself as a more approachable and flexible interlocutor for foreign counterparts than Chinese officials. CCG’s website explicitly says it is “not an organ of the Communist Party of China (CCP) and the Chinese government” and that it is funded through donations and grants from Chinese private sector and multinational corporations.

CCG’s branding as an independent organization allows it to play an important role explaining Chinese government positions to foreign counterparts and testing their reactions to foreign policy ideas without Beijing being committed or facing reputational risks.

CCG’s independent status needs to be treated with caution given its unclear links to United Front Work (UFW) Department operations. For instance, through its founder, Wang Huiyao, who previously served as a State Counselor, CCG was linked to a committee of the Western Returned Scholars Association / Overseas-educated Scholars Association of China (欧美同学会 – 中国留学人员联, WRSA). WRSA calls itself21 as a national organization of Chinese returnees guided by the UFW Department and led by the Central Secretariat (中央书记处领导、中央统战部代管). CCG’s website says Wang remained on the WRSA’s council until 2021, when CCG was 13 years old. While not a direct confirmation, such possible links suggest CCG is likely more closely entwined with party-state structures than it wants to let on.22

This does not diminish CCG’s role in opening channels of communication and fostering dialogue in more flexible formats than official tracks. However, European stakeholders need to be aware of the ambiguity around CCG’s independent status when using the opportunities it offers.

3. International networks and messaging: doing more with less

3.1 Chinese think tanks are expected to shape international geopolitical debates

Chinese think tanks are players within the party state’s strategic endeavors to secure China’s national interests. They are expected to help recalibrating norms of the global international order and adjusting the conceptual frameworks that interpret geopolitical reality. A crucial aspect of this project is reshaping narratives around the themes of multipolarity, multilateralism and global governance – especially within partner countries’ elites. These topics sit at the heart of China-US competition with its global implications, including for the EU.

Such communication efforts are among the key tasks formally required of ‘think tanks with Chinese characteristics’, and implicitly expected of all other think tanks. Much of international activity of Chinese think tanks therefore revolves around destabilizing parts of the US-led international system, while promoting China’s role as facilitator of multipolarization and deterring partners from crossing Beijing’s red lines. This does not necessarily mean using official talking points verbatim. They typically promote broader narratives that align with the fundamentals of party-state messages.

Semi-official and civil think tanks find the task ever more challenging, as they are asked to do more to promote Beijing’s messages with less access to decision-makers and growing administrative constraints. A seminar organized by CCG in October 2023 on the occasion of release of their Global Think Tanks 2.0 (大国智库2.0) report,23 with prominent think tankers and intellectuals such as Shi Yinhong or Lu Xiang, provides a snapshot of the many frustrations in the Chinese think tank community. They must grapple with increasingly restrictive approval processes to engage with foreign actors or travel abroad, after which the emphasis on promoting official messaging impedes their ability to convince foreign audiences with more flexibly tailored messages.

Researchers must also navigate the context created by Beijing’s increasing assertiveness and the underwhelming popularity of official and non-official media content restricted by party-speak. Similar concerns have also been raised by Chinese university think tanks and intellectuals.24

Think tanks amplify the official messages primarily by engaging in track 1.5 and track 2 formats and bilateral exchanges with foreign counterparts. These exchanges target elite audiences and seldom produce publicly accessible outcomes or readouts. The public channels for addressing foreign audiences are interviews with foreign media and China’s own media outlets in English, or other foreign languages (such as Global Times or People’s Daily). Chinese think tankers are frequently asked to comment ahead of or after important events.

3.2 Internationalizing Chinese perspectives through network-building

Chinese think tanks are increasingly pushing new networks and fora with foreign counterparts. Most of these activities carry state-centered themes. Recently, the focus has been shifting from regional cooperation and the “Belt and Road Initiative” towards more overtly political networks, such as the “Global Development Initiative” and the “Global Security Initiative”. Since 2013, more than a dozen think tank networks and dialogue fora have been established for international cooperation and dialogue (See below). With the recent move away from Belt and Road as the main concept for international cooperation, we expect the “Global Development Initiative” and the “Global Security Initiative” to become the leading themes in the near future when Chinese interlocutors reach out to foreign counterparts.

3.3 Three core narratives: Contest, Promote, Deter

Chinese think tanks hold a range of voices on geopolitical affairs (see MERICS China Spektrum project). Yet, the messages amplified for foreign audiences tend to fall into three distinct but interlocking narrative types (see Exhibit 2):

Contesting narratives seek to make an internationally persuasive critique of the current multilateral system’s power imbalances and promote multipolarity. They often critique the United States or the collective “West”, and lean on the party state’s concepts of “true multilateralism” (真正的多边主义) and “multipolarity” (多极化).

Promoting narratives highlight and praise China’s international activity and global initiatives as synergetic with partner countries’ objectives. China is presented as a “win- win” partner that can bring “democratization of international relations”. Chinese initiatives – such as the BRI, Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI), Global Civilization Initiative (CGI) – are presented as constructive alternatives or solutions to the challenges highlighted.

Deterring narratives center on repulsing or preventing undesirable behavior by other international actors. Challenges to Beijing’s national interests, red lines and “internal affairs” (e.g., on Taiwan or human rights violations in Xinjiang) trigger deterring narratives. This often crude form of discursive engagement includes thinly veiled threats, for instance of economic retribution.

3.4 How to avoid painting all Chinese think tanks with a single party-state brush

It is important to maintain a level of nuance and not paint all of China’s think tankers with a single party-state brush. Operating in a constrained system many people will cater to the authorities’ demands, but the agency of those willing to take their own line (sometimes at personal risk) should not be overlooked. This creates an interpretive challenge that international interlocutors need to be intellectually honest about, while limiting the risk of giving in to more elaborate messaging tactics of the CCP.

The positions of China’s think tankers and intellectuals on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are a good case study. The topic is highly sensitive and understandably seen by China’s leadership as relevant to external audiences as shown by frequent statements of foreign policy actors, and as such, messaging around China’s position towards the war is scrutinized.

Still, some think tankers or public intellectuals have at times voiced positions that seem to differ from the official line that politically supports Russia or signals a high degree of alignment between Beijing and Moscow. For instance, Zhou Bo, a former senior colonel at the People’s Liberation Army and senior fellow of the Center for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University, has been contributing opinions to the Financial Times25 and the South China Morning Post26 stating that China is restraining Russia from taking more drastic actions (such as use of nuclear weapons) and painting China’s positioning on the invasion as consistent with non-alignment and opposing spheres of influence.

Feng Yujun, Deputy Dean of International Studies at Fudan University and Director of the Center for Russian and Central Asian Studies and its Center for Shanghai Cooperation Organization Studies, has been consistently critical of Russia’s invasion, Vladimir Putin and his policies calling on China to distance itself from Russia27.

There are several possible interpretation lines:

1. Scholarly courage – This may indeed be an expression of authors own position and at times when it goes counter to the official position, an example of scholarly courage. Particularly if the authors do not enjoy the highest levels of esteem in the Chinese intellectual space that could provide some degree of protection.

2. Useful contrarianism – Lack of punishment by Beijing may be related to either a way of giving limited and curated space to contrarian voices for foreign policy objectives (e.g. China as concerned and considering challenges of Russia giving incentive to embrace wishful thinking about alienation of China-Russia relationship through concessions by “the West”) or as ways to guide and manage the domestic public opinion (proving a constrained space for controlled dissent that can easily be silenced).

3. Designated contrarianism – As above, but the messaging has been deliberately curated and instrumentalized by the party state. In line with “a little badmouth” (小骂大帮忙) tactic28 in which the party state allows friendly actors to voice criticism in order to gain credibility on specific points.

The interpretation toolkit outlined above suggests considering who the message was targeted towards. If it clearly aims at reaching external audiences (being published on non- Chinese platforms or in foreign languages), the message is more likely to be deliberately curated. Still, even the messages published only domestically in Chinese may serve such functions and should be interpreted with a grain of caution, especially if they consistently come from the same author that may be designated as a contrarian view. They should also be treated as an imperfect proxy to what are the relevant debate topics in China and hint at the discussions within the opaque party-state structures.

3.5 Chinese think tanks and the EU: stressing the narrative of „strategic autonomy"

The Covid19 pandemic disrupted direct exchanges between European and Chinese think tankers, including frequent Chinese delegations to Brussels. Prior to the pandemic, the European External Action Service received a delegation of Chinese think tankers roughly every two months, serving as a channel for unofficial exchange. Since travel restrictions ended, the EU has welcomed mostly retired Chinese diplomats in the role of Special Envoy to convey messages to EU officials and assess European views on topics of interest.

Visits and interactions with Chinese think tankers have now resumed, with visits to Brussels by CCG, CICIR, CIIS and CASS. The CCG stands out as a particularly active interlocutor in Brussels as it remained visible in the city throughout the pandemic as the partner of a dedicated EU-China think tank exchange program featuring online meetings and in-person events.

When crafting their messages for European audiences, Chinese think tankers emphasize prospects for coordination, usually in ways that remain thematic rather than discussing concrete action points. The focus is on discouraging policies that might limit Chinese access to European markets and tech; on criticizing the United States; and supporting a notion of European strategic autonomy, interpreted by Chinese think tankers as divergence between the EU and its transatlantic partner. Deterrence-style language is reserved for when China’s ‘red lines’ are transgressed by interlocutors. Xi Jinping Thought is referenced less frequently in conversations with European partners than it is in materials aimed at partners in developing countries. Instead the focus is on geopolitical competition with the United States, the concept of true multilateralism (multipolarity less so, in Europe) and frameworks such as the BRI, GDI, GSI and GCI.

Shaping persuasive messages for European counterparts has become more difficult as tensions have risen. Economic coercion towards Lithuania, the radical and economically harmful zero-Covid policy and Beijing’s sustained support for Russia since the invasion of Ukraine have all decreased strategic trust. Influencing European debates using official Chinese talking-points has therefore become even more challenging. Anecdotal evidence from exchanges with Chinese think tankers keeping to closely stick to official talking points and practice self-restraint during exchanges supports the assessment of a need for greater autonomy and wider parameters.29 Rigid, uninformative exchanges will hinder effective communication and limit critical, open debate that is urgently needed as EU-China relations become ever more turbulent.

4: Conclusions: A realistic view of chinese think tanks' political role is crucial

Chinese think tanks are an important source of policy research and debate in the Chinese system. And even under Xi Jinping, there are still hundreds of smaller think tanks socializing on technical or narrower issues that can operate relatively free also in China. Political ‘duties’ capture those engaging in political debates and critical discussion of extant policy.

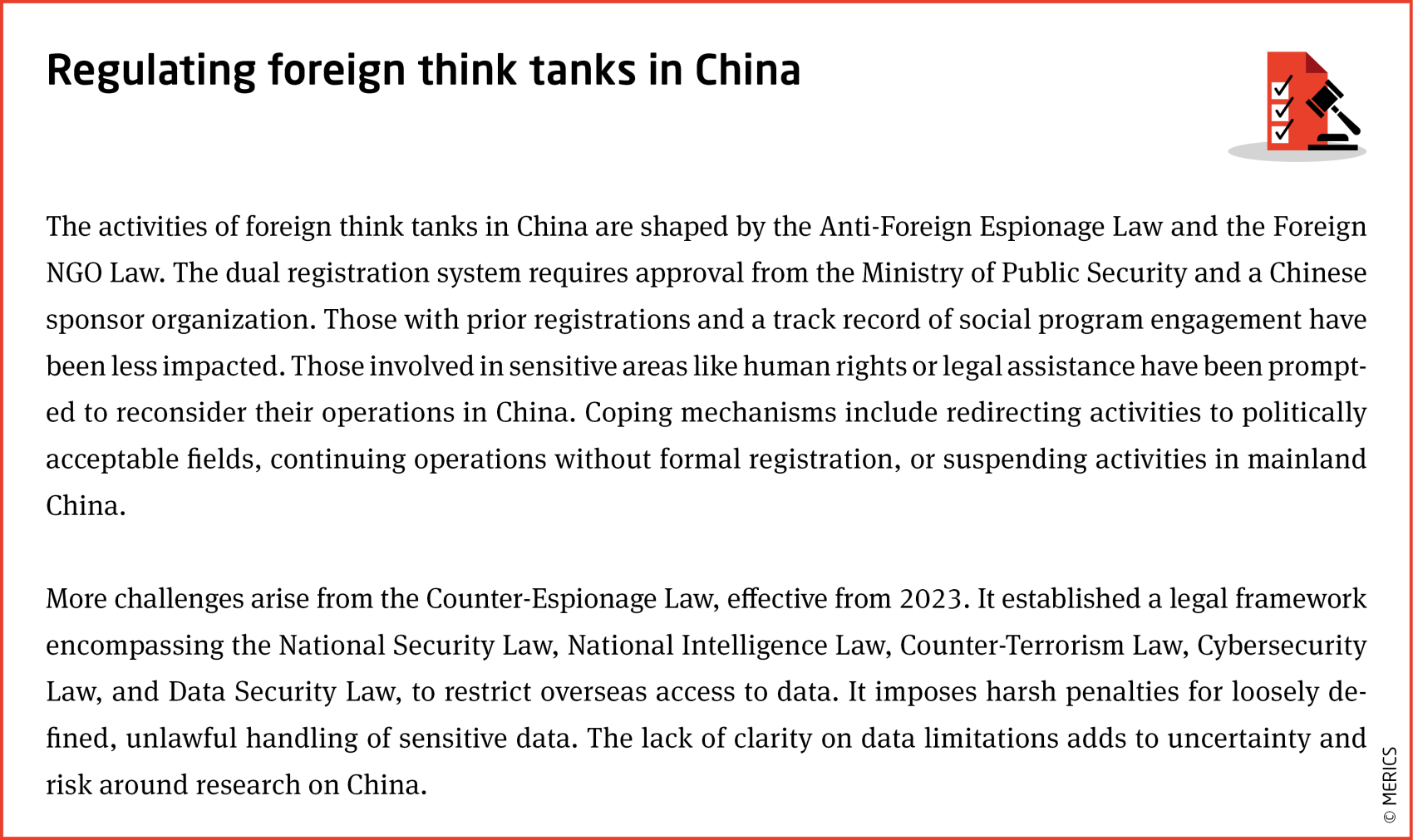

However, over the past decade, regulation of the think tank space has become more restrictive, making independent or critical research and debate close to impossible and pushing think tanks into closer alignment with and support of official party-state objectives and narratives. Organizational integration with the party-state structure, always prevalent, has been tightened by regulations requiring affiliation to a ‘parent’ supervisory body. Foreign interlocutors need to be alert to the restrictions stemming from their counterpart’s affiliation when engaging in dialogue.

Dialogue with “official” think tanks can be an asset. Many of China’s best research and policy think tanks are nested within the party state so they present opportunities to work with partners close to policymaking. Nevertheless, foreign interlocutors must be aware of the political mission that comes with the affiliation and of current official objectives and talking points in their field to identify these elements within the exchanges.

At best, the regulatory environment limits independent and critical research; increasingly, it requires think tankers to communicate official political views and policy. Dialogues on topics Beijing deems sensitive are likely to be especially formulaic. Restrictive regulation and political supervision hampers exchanges with Chinese interlocutors as they risk career repercussions, or even their personal safety should they stray too far from Beijing’s position. The controls on data in the revised Anti-Espionage Law highlight this by creating a wide net for state action.

There is a push towards international communication from Chinese think tanks, most often official and semi-official ones with strong state-backing and funding. These exchanges typically follow the communication patterns we have identified as “contest, promote, deter”. As China’s leaders are prioritizing a battle for global discourse power with the “West”, it is likely that Chinese think tanks will be seen to take an increasingly activist stance towards defending and promoting official viewpoints in future and critical debate will become harder.

The qualitative exchange in closed-door meetings may be hard to capture objectively. But the changes in think tank-related policy initiatives and focus topics point to closer alignment with party-state discourse. The trend is clear: whether by choice of by force, Chinese think tanks have been tasked to be more vocal and active in communicating Beijing’s political ideas and views to a global audience.

Given the changing regulatory environment towards a logic that favors organizations showing political utility, and squeezing out those that do not, the think tank space must be expected to remain a highly politicized sector for the time being. Engagement with them remains beneficial, but it is crucial that European actors enter in the exchanges clear-eyed towards role and circumstances that their Chinese counterparts navigate.

* Responding to this report, CCG has issued a statement emphasizing their role as a non-governmental and non-party identity devoted to enhancing communication between China and the international community. You can read the statement here on CCG's website.

Appendix

- Endnotes

-

1 | McGann, James G (2021). "2020 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report." University of Pennsylvania.

January 28. https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/182 | Wang, Limin王利民 et al. (2022). “Chinese Think Tank Directory No.5” [中國智庫名錄No 5 ]. Jan 1. https://www.pishu.com.cn/skwx_ps/bookdetail?SiteID=14&ID=13663523#

3 | Zhu Xufeng (ed.) (2013). “The Rise of Think Tanks in China”. Routledge. February 7. https://www.routledge.com/The-Rise-of-Think-Tanks-in-China/Zhu/p/book/9781138954694

4 | Peng Dannie, SCMP (2023). “China names new science ministry chief to help lead hi-tech self-reliance drive.” October 9. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3237228/china-names-new- science-ministry-chief-help-lead-hi-tech-self-reliance-drive. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

5 | China Center for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE). Website. http://english.cciee.org.cn/.

Accessed: March 8, 2024.6 | This is not uncommon also elsewhere (take e.g. the Brookings Institute), however the bureaucratic ranking system applicable to Chinese official organizations means that these TT are more narrowly identifiable as formal party-state organizations.

7 | Chaoyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University (RDCY). Website. http://rdcy.ruc.edu.cn/ zw/gywm/RDCYjj/index.htm. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

8 | Common legal statuses are: corporate (企业); non-corporate private entity (民办非企业); non-governmental organization (社会团体); foundation (基金会).

9 | Cheng Li (2022). “A Ladder to Power and Influence: China’s Official Think Tanks to Watch”, China US Focus. October 14. https://www.chinausfocus.com/2022-CPC-congress/a-ladder-to-power-and- influence-chinas-official-think-tanks-to-watch. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

10 | Unirule Institute of Economics (UNIRULE). Website. http://english.unirule.cloud/, Accessed: March 8, 2024.

11 | Kuo Lily, The Guardian (2019). “Chinese liberal thinktank forced to close after being declared illegal”. August 28. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/28/chinese-liberal-thinktank-forced-to-close-after-being-declared-illegal. Accessed: March 8, 2024. Scholars at Risk Network (2019). “Incident Report – Unirule Institute of Economics shut down”. August 26. https://www.scholarsatrisk.org/report/2018-08-26-unirule-institute-of-economics/. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

12 | Its impact on Chinese national policy-making is questionable, given its critical stance towards much of the party-state’s economic policy. Nevertheless, it was one of the best-known centers for liberal economic thought in China. McGann, James G (2012). "2012 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report." University of Pennsylvania. December 1. https://repository.upenn.edu/entities/publication/ed53ecd9-5a6b-44da-be00- 528d6ec97dc7

13 | China File (2013). “Document 9: A ChinaFile Translation”. November 8. https://www.chinafile.com/

document-9-chinafile-translation. Accessed: March 8, 2024.14 | CCG (2023). “CCG Update - Chinese think tanks aspire to thrive with independence and internationalization”. Oct 9. https://ccgupdate.substack.com/p/chinese-think-tanks-aspire-to-thrive. Accessed: March 8, 2024; Wang Huiyao, Miao Lü (2023). Global Think Tanks 2.0 [大国智库2.0 ]. CCG. August 1. http://www.ccg.org.cn/archives/77761. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

15 | The Government of the People’s Republic of China (2017). Opinions on the Healthy Development of Social Think Tanks [关于社会智库健康发展的若干意见]. May 4. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-05/04/ content_5190935.htm. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

16 | School of Public Policy & Management, Tsinghua University (2012). “Profile of Hu Angang” [胡鞍钢 ]. October 29. https://www.sppm.tsinghua.edu.cn/english/info/1135/2054.htm. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

17 | Hayward Jane. “The Rise of China's New-type Think Tanks and the Internationalization of the State”.

Lecture Series. Cornell University Contemporary China Initiative. filmed March 25, 2018. Video of lecture, 54:56. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yeEuKICd7T0. Accessed: March 8, 2024.18 | The State Council of the PRC (2015): “Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of a New Type of Think Tank with Chinese Characteristics” (中共中央办公厅、国务院办公厅印发《关于加强中国特色新型智库建设的意见》), January 20. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2015-01/20/content_2807126.htm. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

19 | Its founder is an alumni of Renmin University.

20 | China Institute of International Studies (CIIS). Website. https://www.ciis.org.cn/english/. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

21 | Western Returned Scholars Association; Overseas-educated Scholars Association of China (2018). “Western Returned Scholars Association (Overseas-educated Scholars Association of China) A Brief Introduction” (欧美同学会(中国留学人员联谊会)简介). January 2. https://web.archive.org/web/20240325101233/http://www.wrsa.net/content_40128737.htm. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

22 | CCG (2015). „Profile of Wang Huiyao – Archived” [王辉耀]. March 29. https://web.archive.org/web/20150329165723/http:/ccg.org.cn/Director/Member.aspx?Id=1120 . Accessed: March 8, 2024.

23 | CCG (2023). “CCG Update - Chinese think tanks aspire to thrive with independence and internationalization”. Oct 9. https://web.archive.org/web/20240325102106/https://ccgupdate. substack.com/p/chinese-think-tanks-aspire-to-thrive . Accessed: March 8, 2024.

24 | Institute for AI International Governance, Tsinghua University (2022). “Innovative exploration of university think tanks in improving international communication capabilities in the new era”. [新时代 高校智库提升国际传播能力的创新探索] July 1. https://web.archive.org/web/20221202183438/https:/aiig. tsinghua.edu.cn/info/1368/1600.htm. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

Guo Rui, Jun Mai, Zheng William, SCMP (2023). “For China’s intellectuals, restrictions started long before the pandemic and will continue after Covid is over”. January 2. https://www.scmp.com/news/ china/politics/article/3205309/chinas-intellectuals-restrictions-started-long-pandemic-and-will- continue-after-covid-over. Accessed: March 8, 2024.25 | Zhou Bo, The Financial Times (2022), ”China can use its leverage with Russia to prevent a nuclear war”. https://www.ft.com/content/f05fef3f-a8be-4007-a161-34764419847f. October 27. Accessed on March 8, 2024.

26 | Zhou Bo, SCMP (2023), ”Ukraine war: how China can get the world to step back from nuclear Armageddon”, scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3233136/ukraine-war-how-china-can-get-world- step-back-nuclear-armageddon, September 4, Accessed on March 8, 2024.

27 | Feng Yujun (2022) “Watching the war situation between Russia and Ukraine, we should carefully reread Chairman Mao Zedong’s "On Protracted War"“ [观察俄乌战局,应该仔细重读毛泽东主席的《论持久战》], https://web.archive.org/web/20240302045838/https:/mp.weixin.qq.com/s/mOATITiJYQZP4NPH- l2IpQ, March 14. Accessed on March 8, 2024. [For English-language translation see Sinification newsletter: https://www.sinification.com/p/why-china-should-have-distanced-itself]

28 | Ohlberg Mareike, Hamilton Clive (2020), ”Hidden Hand: Exposing how Chinese Communist Party is reshaping the world”, Australia: Hardie Grant.

29 | CCG (2023). “CCG Update - Chinese think tanks aspire to thrive with independence and internationalization”. Oct 9. https://ccgupdate.substack.com/p/chinese-think-tanks-aspire-to-thrive. Accessed: March 8, 2024.

This report was last updated on May 15, 2024.