Resilience and decoupling in the era of great power competition

How the fight between China and the US for geopolitical dominance has ruptured the world economy

Main findings and recommendations

- The United States and China are engaged in a new cold war. Economic and especially technological ties between the two countries are being ruptured to harm the other side. The outcome is a decoupling of the world’s two biggest economies.

- Economic decoupling is part of a power struggle between the US and China for geo-economic and geopolitical dominance.

- These tensions represent a radical departure from the spirit of globalization, an approach to policy characterized by the belief in open borders, free trade and a rule-based settlement mechanism.

- The era of globalization generated strong economic interdependence between the US and China and created new power imbalances in the global economy. The US in particular controls the nodal points in important value chains and is using them to assert its geopolitical and geo-economic interests, as is China, to a lesser extent.

- As interdependence has become a weapon in the geopolitical arena, so its use has reinforced economic decoupling as the rivals have put more emphasis on the pursuit of improved national security.

- Decoupling is particularly evident in the semiconductor industry, which is a key sector for technological competition. The US has the upper hand and is trying to cut off China’s global telecoms giant Huawei from the Western technosphere.

- The experience of the Covid-19 pandemic has increased the desire for greater economic autonomy and resilience, which is reinforcing the already existing trend towards decoupling.

1. “Chimerica is dead” – Two closely intertwined economies want to disentangle

Fourteen years ago, the British historian Niall Ferguson, together with the German economist Moritz Schularik, invented the term „Chimerica“ to describe the hitherto symbiotic economic relations between the United States and China. As recently as last year, when the trade war between the two countries was already in full swing, the US imported goods worth around USD 450 billion from China. Conversely, US exports worth USD 107 billion flowed into China. With the income from the trade surplus, China is buying US government bonds in large numbers and has amassed US government bonds worth well over a trillion dollars. Until recently, the two largest economies in the world seemed like Siamese twins.

"Today, Chimerica is dead," Ferguson states with the certainty of a pathologist, adding, "Trump has extended the trade war with China to the technology sector and the monetary sector. We are in a new cold war." US President Donald Trump delivered the declaration of war in mid-May: "We could break off the entire relationship (with China) and save 500 billion dollars," he threatened on his favorite American news channel, Fox News.

Separating two economies that are so closely intertwined is easier said than done. To do so would halt, or even reverse, the globalization of the world economy, which received an enormous boost when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Four years later, the US journalist Thomas Friedman published a book whose title summarized the spirit of the times in one sentence: "The World is Flat," Friedman’s 2005 book became a bestseller, translated into nearly 40 languages.

Friedman‘s bible of globalization was the logical continuation of American political scientist Francis Fukuyama‘s epochal work, „The End of History“. Just as Fukuyma, in 1992, predicted a triumphal march of liberal democracy in the 21st century, following on from the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Friedman forecast that all players in the world economy would benefit from globalization. According to his thesis, free trade and technical progress provided for a global marketplace where everyone had equal opportunities. He argued that although countries’ influence and prosperity and that of their people were still primarily determined by their history and geography up to the turn of the millennium, the unequal legacy factors would be disempowered by new technologies such as the Internet and the globalized trade unleashed by digital technology. Geopolitical and geo-economic hierarchies would be leveled in the 21st century.

2. Globalized value chains lead to power imbalances between China and the US

Contrary to the hopes of its supporters, globalization did not flatten the world, and has created new power imbalances. "Globalization, in short, has proved to be not a force for liberation but a new source of vulnerability, competition, and control; networks have proved to be less paths to freedom than new sets of chains," according to Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman. With their 2019 essay "Weaponized Interdependence" the two US political scientists from Washington D.C. invented the deglobalization era’s zeitgeist phrase.

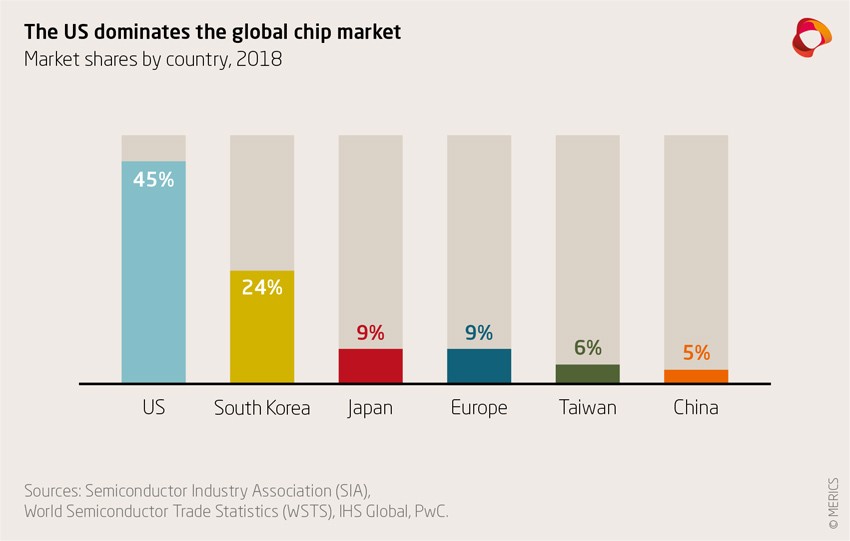

Farrell and Newman rightly argue, that in our interconnected world, power depends on who controls the intersections because these nodes are also the new switching points of power. Nowhere is this more evident than in the global value chains. Take computer chips for example: Almost half of the world‘s semiconductor products come from US factories. This gives the US a lever of power that Trump has already used successfully against China.

In April 2018, the US president imposed an embargo on the Chinese telecom supplier ZTE; it brought the company, which has annual sales worth 17 billion USD and a workforce of 75,000, to the brink of collapse. The embargo was imposed because ZTE had violated US sanctions against Iran and North Korea. ZTE is dependent on US-made microchips because China‘s own share of the global chip market is a mere five percent. China spends more on importing the building blocks of the digital age than it does on oil imports. At the request of China’s President Xi Jinping, Trump rescinded the "death sentence" on ZTE after three months in order to revive stalled trade talks with Beijing.

But China also knows how to turn its economic power into a weapon. When the governments in Beijing and Tokyo got into a conflict over control of the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea in 2010, China imposed an embargo on exporting rare earths to Japan, its past and present regional rival. China has a power lever in the vital rare earth minerals market, as it tops 80 percent of global market share in the 17 metals used to build smartphones, electric cars, satellites and fighter planes, and other essential smart hardware. In addition, with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is in the process of establishing a new network of financial and economic dependencies that allow Beijing to pull on the geopolitical strings in a network of relationships with primarily developing countries.

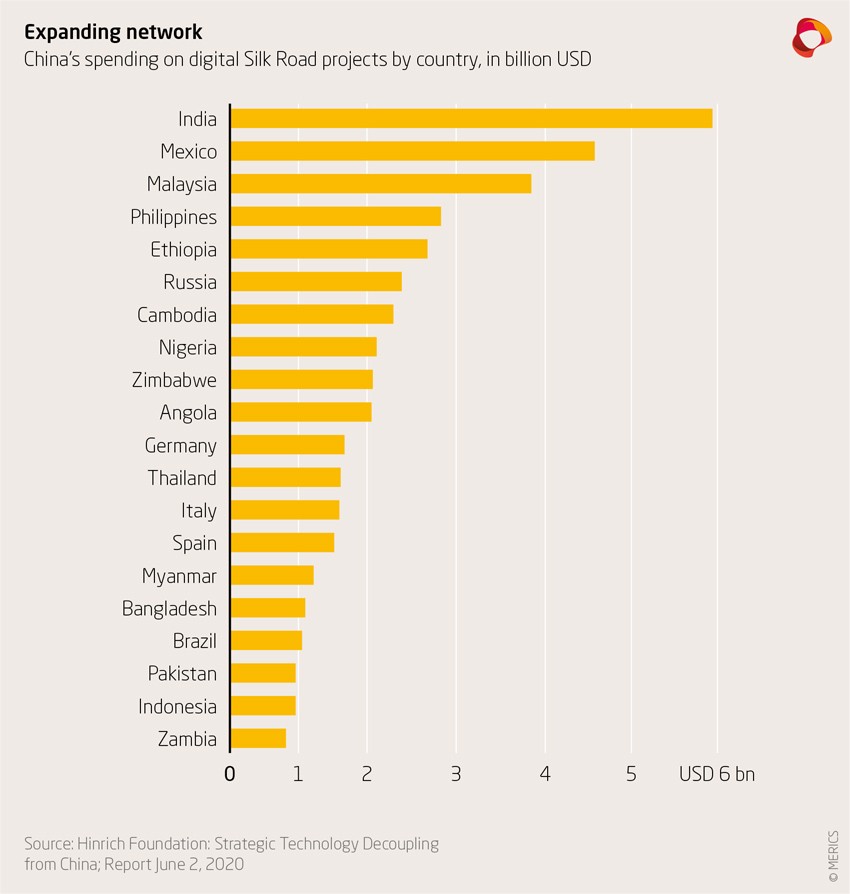

However, the impact of the BRI’s so-called "new Silk Roads" is not limited to conventional transport routes. Even more important are the "digital Silk Roads" in cyberspace, which China could control through the domination of 5G, the fifth generation of the mobile phone standard. The 5G technology is set to become a central hub of the global digital economy, thereby creating new dependencies. „Huawei‘s 5G networks will be at the heart of an ecosystem of Chinese technology companies which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is using to build a digital Silk Road,“ has warned Alex Capri, Research Fellow at the Hinrich Foundation in Hong Kong, in a report entitled „Strategic Technology Decoupling from China.“ Capri foresees China’s major tech players gaining dominant positions in Silk Road regions. China’s Beidou satellite network would provide the GPS services to entire regions; Alibaba and Tencent would enable cloud and e-commerce services; other large Chinese companies such as Hikvision and Dahua Technology (a maker of facial recognition CCTV), SenseTime and Megvii (artificial intelligence, AI) would be building the AI and data analysis frameworks.

It is this asymmetry of dependencies in the globalized world economy that gives countries like China and the US the power to turn such interdependencies into a means of exerting pressure in the geopolitical arena.

3. The new cold war is also fought in the digital sphere

Huawei is the world market leader in 5G technology. For many countries, this Chinese telecom giant is their only chance to participate in the next stage of the digital revolution in the foreseeable future. Network components from Huawei are cheaper than the competition. They also often have a head start because they have already delivered the infrastructure for the 4G network or the cloud infrastructure. In the US, in particular, but also in Europe, this has fueled fears that China’s government could use Huawei to put political pressure on other countries – whether through espionage or so-called "kill switches" to paralyze system-important infrastructures such as communication channels or energy supply. Part of Huawei‘s success rests on consistent strong support from the government in Beijing.

According to research by The Wall Street Journal, subsidized loans, tax breaks and other state aid add up to the equivalent of 75 billion USD between 1998 and 2018. Only in this way is it possible for the Chinese group to undercut competitors’ prices by up to 30 percent, and to offer customers favorable financing terms. In 2009, for example, the government of Pakistan received a 20-year interest-free 124 million USD loan from China’s Export-Import Bank to purchase surveillance technology for deployment in the capital city, Islamabad. "The stipulation: the job would be awarded to Huawei, with no competitive bidding," Capri writes in the Hinrichs report.

The US government also suspects Huawei has close ties to the CCP-leadership in Beijing and accuses the company of espionage. "Huawei is very dangerous," said US President Trump in May 2019, shortly after his administration had placed the Chinese company on the Entity List, a blacklist of companies that the US government believes threaten national security. As a result, US companies can now only supply US technologies to Huawei prior approval by the authorities. Google reacted immediately, excluding Huawei smartphones from updates to the Android operating system and from applications such as Gmail or Google Maps.

4. Decoupling could split the global market into competing technospheres

The misuse of mutual dependencies in the global economy, which are being deployed as weapons in a geopolitical power struggle, is causing nations to distance themselves from each other. Huawei’s immediate response to the US embargo was to introduce its own operating system, called "Harmony," in August 2019. However, there can no longer be any talk of harmony: the dispute over Huawei is the most visible sign yet of technological decoupling between the US and China. At its most extreme, decoupling could split the global market into two or more technospheres.

The emerging trend towards self-reliance and preference for shorter supply chains was strengthened by the Covid-19 pandemic when vital medical products and protective equipment were suddenly lacking in many countries because borders were closed and export bans imposed. Hinrichs fellow Capri speaks of "techno-nationalism." The US, the EU and other state actors can be expected to put greater focus on countering Beijing‘s economic nationalism with their own techno-nationalist initiatives. Global value-added chains are thus being transformed from blessing to curse. Instead of just-in-time delivery, which has been optimized down to the smallest detail, the security of the just-in-case economy is now gaining the upper hand.

Under the banner of liberalism and globalization, borders have been opened, walls have been torn down and trade barriers dismantled. Now the pendulum is swinging back: new walls and hurdles are being erected, old connections are being cut in order to control global trade, financial and data flows as well as worldwide migration movements.

However, decoupling from China will not be as easy as the Trump administration‘s financial and techno-warriors imagine. Global value chains today are so complex that the rupture of one supply chain often leads to collateral damage at another point in the international division of labor.

As Farrell and Newman have written in the journal Foreign Affairs, decoupling from China resembles attempting to separate Siamese twins, with common organs, nervous system and blood circulation. They warned, "Today’s policymakers can vaguely grasp that some healthy-seeming economic relationships have become dangerous and some even gangrenous. But they don’t know which relationships should be saved, which should be severed, and which should be rearranged – and they are working with little more than prayers and blood-speckled hacksaws."

The use of economic dependencies as a political weapon is producing a paradigm shift in a world that has regarded ever-closer interconnections as the ultimate, historic goal of economic progress. Suddenly, too much closeness causes risks, while distance creates security. There have been relapses into national egoisms and isolation throughout history. But when the US, as the leading and most powerful nation on earth, made "America First" the maxim of its policy overnight, it disrupted the world order.

For Donald Trump, the world is not a place of brotherhood anyway, but an arena in which nations compete for economic and political power. "These competitions (with China and Russia) require the United States to rethink the policies of the past two decades – policies based on the assumption that engagement with rivals and their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners. For the most part, this premise turned out to be false," said the president’s 2017 National Security Strategy.

It is nothing new for the US to make national security a maxim for dealing with other nations. In Trump‘s world, however, there is no longer any common security; allies exist at best for a limited period of time to achieve short-term national goals. Trump has replaced the formula of the „coalition of the willing“ invented by former US President George W. Bush during the second Iraq war, with a national solo effort. "The president embarked on his first foreign trip with a clear-eyed outlook that the world is not a "global community" but an arena where nations, nongovernmental actors and businesses engage and compete for advantage," Trump‘s then security and economic advisors Herbert R. McMaster and Gary Cohn wrote in May 2017 in The Wall Street Journal. This set the course of the "America First" policy: National security can therefore only exist if America is economically, technologically and politically in the lead.

In this all-encompassing national security thinking, the economy is also a "weapon," whether for self-defense or for attacking rivals. Penalties, investment controls, embargoes, sanctions, industrial policy – all serve national security which, as a reason of state, must not be questioned either politically or economically. Open societies thus become national strongholds, controlling everything that goes in and out on their drawbridges: goods, services, capital, data, ideas and people.

The Swiss management consultant Heiko Borchert, who does intensive research on how geopolitical changes impact companies, calls this "flow control." The phrase denotes a country‘s ability to control the framework and conditions for strategically important cross-border trade, financial, data and migration flows. "The most important instruments that have been used to date to connect nations – rules, international institutions, technical standards and economic relations – are now being turned against each other," Borchert has said. Ultimately, it is a matter of using these geo-economic "weapons" to assert geopolitical interests against other countries.

Until recently, Aimen Mir was among the guardians of US national security. Until early 2019, Mir headed the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States, better known and feared under the acronym CFIUS. The relatively obscure committee holds one of the most powerful levers the US government has to pull up the nation’s drawbridges against unwelcome inbound foreign direct investment. CFIUS is a watchdog committee that scrutinizes foreign investors, e.g. in company takeovers, from a national security perspective, and rejects them if necessary.

In each of the years 2017 and 2018, more than 150 transactions were examined in detail, more than double the number scrutinized in previous years. By far the largest share of this was attributable to Chinese investors. "The change of heart towards foreign investment already began in the Obama administration and is mainly due to the fact that China has been seen as a strategic competitor of the US since then.

Under President Trump this development has continued and accelerated once again," Mir said in a 2019 conversation. New technologies are becoming increasingly important for US national security, he said: "In the past, national security authorities concentrated on areas such as nuclear capabilities, microelectronics, stealth and space technology in order to be superior to potential adversaries. Today, topics such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology and robotics are likely to play a decisive role."

5. Foreign investment gets stricter oversight in the US and the EU

CFIUS includes representatives from various US government departments. The committee‘s power was shown most recently in 2018 when it blocked the 117 billion USD purchase of US chip manufacturer Qualcomm by Singaporean firm Broadcom. The previous year, CFIUS prevented the purchase by Chinese investors of the US chip manufacturer Lattice. The takeover of US semiconductor manufacturer Cypress by German group Infineon Technologies AG also came close to failure because of a CFIUS veto, according to a report by the news agency Bloomberg. Infineon had to give additional security guarantees before the acquisition could go ahead. The reason for US mistrust in this case was also China, as Infineon generates about one-third of its sales there. Huawei is one of Munich-based Infineon’s customers.

At the beginning of 2020, the Trump administration significantly expanded the reach of CFIUS. All US companies that produce "critical technology" or perform important infrastructure tasks or process sensitive data of US citizens need CFIUS approval, even in the absence of a foreign takeover bid.

Where the US led, others soon followed by tightening their own regulations on foreign ownership. Similar controls on foreign investment now exist in the EU. The Screening Regulation adopted by the EU Commission and member states in March 2019 says regulators should "take into account all relevant factors, including the impact on critical infrastructure, technologies (including critical enabling technologies) and inputs that are essential for security or the maintenance of public order and whose disruption, failure, loss or destruction would have a significant impact in a Member State or in the Union."

Controls on foreign ownership are also being tightened at national level. Germany’s foreign trade law has already been made stricter and there are plans to take a closer look at transactions involving "critical technologies." As economics minister Peter Altmaier explained in November 2019: "If public order or security in Germany could be impaired, we can pull the ripcord and consider a buyout and, if necessary, ban it." Altmaier has emphasized that Germany continues to welcome investments from China. However, considerations of national and European security are becoming an important barrier to foreign control and there is a greater willingness, if necessary, to interrupt the flow of capital and technology.

"Even if the two superpowers are able to resolve the ongoing trade tensions and negotiate a series of trade agreements, there will be no going back from the omnipresent effects of techno-nationalist policies," warned Research Fellow Alex Capri a December 2019 report from the Hinrich Foundation. It said the trade conflict is only "a subset in a much larger, overarching, systemic rivalry between two superpowers, which is the defining issue of this century."

Chinese diplomats share this big picture view of the tensions: "There are many reasons for the US to wage a trade war with China, but they are not the real motives: behind it is the waging of a technological war to slow down China‘s growth in the field of technological progress," according to Liu Xiaoming, the PRC’s ambassador to London, speaking in late May 2019.

The Hinrich study concludes that US-China decoupling is inevitable in the technologically vital semiconductor industry. For US semiconductor companies to decouple from the Chinese market would have "traumatic effects on the entire technology industry and change the global economic landscape. Given its strong dependence on US technology, China has no choice but to step up efforts to "de-Americanize" its supply chains, the Hinrich study concludes. It is not alone in its assessment. "The market for chips is 100 percent controlled by Americans," the Chinese star entrepreneur and Alibaba founder Jack Ma warned during an April 2018 visit to Waseda University, Japan.

Although it is not 100 percent, almost half of the 155 billion USD global semiconductor market is dominated by US companies, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association. The US government is using the dominance of its chip manufacturers as a further weapon to isolate telecom supplier Huawei from international supply chains. The US Department of Commerce amended the so- called "Foreign Direct Product Rule" in mid-May 2020. The rule allows the US government to restrict the use of US technology by foreign companies for military or national security products. Foreign manufacturers also have to apply for export licenses for many chips if they produce semiconductors using US-developed machinery or software and intend to supply chips to Huawei.

This gives the Commerce Department a lever to block, for example, the sale of semiconductors by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), one of the most important suppliers of computer chips for Huawei. The Nikkei Asian Review reported shortly after the US government‘s decision that TSMC was no longer accepting new orders from Huawei.

6. US-Chinese decoupling has a widespread impact on several levels

Techno-nationalist policies have also stirred fears in US academia’s lecture halls and research laboratories. About 360,000 foreign students are from China, roughly one-third of all foreign students at US universities. Furthermore, the US and China are connected through research cooperation. For example, Microsoft’s largest research center outside its home country is in Beijing, with 200 local scientists and around 300 fellows from the academic world.

But the two countries are now keeping their distance in the exchange of people and ideas. For instance, in June 2018 the US State Department shortened the visas permitted to Chinese post-graduate students in "sensitive areas" from five years to one. At the same time, US intelligence services warned against China‘s "thousand talent" initiative. The program, established for more than a decade, exists to tap into the knowledge of PRC citizens trained or employed overseas by encouraging researchers to return to China.

A White House report on "China‘s economic aggression" from June 2018 devotes two chapters to the dangers of undesirable knowledge transfers and warns: "The risks to national and economic security are that the Chinese state could attempt to manipulate even ignorant or unwilling Chinese citizens or put pressure on them to collect information that serves Beijing‘s military and strategic ambitions."

Decoupling attempts therefore go beyond the control of trade, capital and data flows. For example, the often opaque accounting practices of Chinese companies have prompted US Congressional initiatives to tighten the legal requirements and controls for foreign companies to list on US stock exchanges. Chinese companies such as Baidu that are listed on Nasdaq, the New York technology stocks exchange, are already looking to other stock markets to protect themselves from the prevailing anti-Chinese mood in the US. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has instructed the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board which holds state pension funds to stop investing in Chinese companies.

Convinced free traders like Robert Zoellick, who was the US Trade Representative during the presidency of George W. Bush, see the current trajectory leading to a new technological Cold War. Zoellick’s appointment as USTR in 2001 coincided with China’s entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Like many policymakers of that era, he had long hoped that WTO membership would bring China closer to the Western model through integration into the world trade order. Zoellick now warns of the progressive decoupling of their economies: "We are already in the age of the splinter Internet. I expect a decoupling of telecommunications, Internet and ICT services as well as 5G systems," he predicted in late 2019.

Zoellick‘s concerns are not only related to Trump‘s aggressive trade policy. Contrary to all the window-dressing by China’s President Xi Jinping on free trade and international cooperation, the PRC’s leadership is stirring up systemic competition with the West. The China model is also to be exported to other countries. Since it began opening up its economy in 1978, the CCP remained primarily concerned with securing its power at home. With the arrival of the digital age, the "Great Firewall" was added to the already-existing framework of information control. However, CCP strategists have since switched to the offensive and are in the process of creating a cross-border technosphere with Chinese characteristics.

The digital silk roads have an important role to play as China’s government seeks to export technologies such as 5G, and also its ideas about surveillance and control in the digital age. "Technology is making life for authoritarian regimes easier," says British historian Peter Frankopan.

According to a September 2019 study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, China is by far the driving force behind the global spread of smart surveillance technologies. The Washington-based think tank’s study found 63 countries use Chinese control systems that work with artificial intelligence (AI). Huawei alone supplies 50 nations worldwide with surveillance technology. Of the buyers of Chinese technology, 36 countries are involved in Beijing‘s Silk Road initiative. Not all of them deploy it to suppress citizens’ freedom. But technology exports also include facial recognition and so-called "smart policing", i.e. access to and evaluation of large amounts of data for law enforcement purposes. "It is not surprising that countries with authoritarian systems and low political rights invest heavily in surveillance techniques using artificial intelligence," the Carnegie study states. Reporters from the Wall Street Journal found out in the summer of 2019 that "Huawei technicians have helped government officials in both Uganda and Zambia to spy on political opponents."

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated decoupling between the US and China. After all, protecting the health of their own people has become the main task of many governments. Even if nobody knows when and how the virus will be eradicated, it can already be said that resilience and above all adaptability will become new jokers in the geopolitical power poker and can have a lasting effect on its outcome.

The pandemic has highlighted the internal strengths and weaknesses of China, the US and Europe to the world. None of them have shown up well in this stress test. "The Covid-19 crisis augurs three watersheds: the end of Europe’s integration project, the end of a united, functional America, and the end of the implicit social compact between the Chinese state and its citizens", is the gloomy assessment from economist Arvind Subramanian, a former chief advisor to India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and currently based at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) in Washington, writing in an op-ed for the author network Project Syndicate. Even if one does not accept Arvind’s full conclusions, many would agree with his prediction that "all three powers will emerge from the pandemic weakened."

It therefore matters greatly for the relative balance of power which region finally emerges as hardest hit by the pandemic crisis and proves least able to withstand it. There are certainly differences that could also play an important role for the future international power structure. Apart from inner strength, it also depends on which social and economic model has proved to be particularly crisis-proof in the eyes of the world. "Weak, fractured societies, no matter how rich, cannot wield strategic influence or provide international leadership – nor can societies that cease to remain models worthy of emulation," Subramanian writes.

For former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, it is already foreseeable that neither a new Pax Sinica nor a renewed Pax Americana will rise from the ruins of the coronavirus crisis. In an article for the magazine "Foreign Affairs," Rudd predicts that China and the US in particular will suffer severe setbacks to their power ranking.

In April 2020, The Eurasia Group made one of the first comparisons of the resilience of individual nations in the pandemic at a presentation in New York. It found Scandinavian countries such as Norway had so far coped well with the crisis, while Germany, South Korea, Japan and Switzerland also were also proving resistant and adaptable to the virus. "The crisis-resistant countries combine a high level of political performance, social cohesion and good health care with low financial vulnerability. If there is one weakness in this group, it is the vulnerability of their economies to a global downturn," said Eurasia expert Alexander Kazan.

The two superpowers, the US and China, did not make it into the top 10 nations in Eurasia’s list, coming in at 11th and 12th place, respectively. Since then the US has fallen well behind with infections but also deaths rising rapidly.

- Endnotes

-

1 | Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick: “Chimerica and the global asset markets”; International Finance 10:3, 2007: pp. 215–239 DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2362.2007.00210.x

2 | Niall Ferguson: “Ich befürworte einen neuen Kalten Krieg“; Handelsblatt; 05.09.2019; https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/international/historiker-ferguson-im-interview-ich-befuerworte-einen-neuen-kalten-krieg/24976714.html; Accessed June 10th 2020

3 | Fox Business News: Trump on China. “We could cut off the whole relationship”; https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/trump-on-china-we-could-cut-off-the-whole-relationship; May 14th 2020; Accessed June 2nd; 2020

4 | Thomas Friedman: The World is Flat; Farrar, Straus and Giroux; New York 2005.

5 | Francis Fukuyama: The End of History and the Last Man ; Free Press, 1992

6 | Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman: “Chained to Globalization”; Foreign Affairs; January/February 2020. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2019-12-10/chained-globalization; Accessed Jun2 2nd 2020.

7 | Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman: “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion,” International Security, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Summer 2019), pp. 42–79, doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00351.

8 | Alex Capri: “Strategic US-China decoupling in the tech sectors”; Hinrich Foundation; June 2020;

9 | Wall Street Journal: “State support helped fuel Huawei’s global rise”; December 25th2019; https://www.wsj.com/articles/state-support-helped-fuel-huaweis-global-rise-11577280736; Accessed Jun14th 2020.

10 | Washington Post: “Trump calls Huawei ‘dangerous’ but says dispute could be resolved in trade deal“; May 24th 2019; https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/trump-calls-huawei-dangerous-but-says-dispute-could-be-resolved-in-trade-deal/2019/05/23/ed75c4a0-7da6-11e9-8ede-f4abf521ef17_story.html; Accessed Jun 14th 2020

11 | Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman: “The Folly of Decoupling from China”; Foreign Affairs; June 3rd 2020; https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-06-03/folly-decoupling-china; Accessed June 3rd 2020.

12 | National Security Strategy of the United States; December 2017; https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905-2.pdf; Accessed June 10th 2020

13 | Wall Street Journal: “America First doesn’t mean America alone”; May 30th 2017; https://www.wsj.com/articles/america-first-doesnt-mean-america-alone-1496187426; Accessed Jun2 12th 2020

14 | Conversation with the author in February 2020.

15 | Conversation with the author in April 2019.

16 | Bloomberg: “Infineon Agreed to U.S. Security Concessions for Cypress Deal“; March 13th2020; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-13/infineon-agreed-to-u-s-security-concessions-for-cypress-deal; Accessed Jun2 10th

17 | European Union: Regulation (EU) 2019/452 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 March 2019 establishing a framework for the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union; https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019R0452&from=EN; Accessed Junes 10th 2020

18 | Alex Capri: “US-China Tech War and Semiconductor”; Hinrich Foundation; December 2019

19 | South China Morining Post: Technology is true target of US attack on China, says diplomat; May 24th 2020; https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3011638/technology-true-target-us-war-china-says-diplomat; Accessed June 12th 2020

20 | South China Morning Post: “Countries need to break free of US dominance of semiconductor industry, says Alibaba’s Jack Ma“; April 25th 2018; https://www.scmp.com/tech/china-tech/article/2143352/countries-need-break-free-us-dominance-semiconductor-industry; Accessed June 14th 2020

21 | Asian Nikkei Review: “TSMC halts new Huawei orders after US tightens restrictions“; May 18th 2020; https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Huawei-crackdown/TSMC-halts-new-Huawei-orders-after-US-tightens-restrictions; Accessed June 10th 2020

22 | White House: “How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World“; June 2018; https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/FINAL-China-Technology-Report-6.18.18-PDF.pdf; Accessed June 10th 2020.

23 | Robert B. Zoellick: “Can America and China be Stakeholders”; Speech at the US-China Business Council, Washington; December 4th 2019; https://www.uschina.org/sites/default/files/ambassador_robert_zoellicks_remarks_to_the_uscbc_gala_2019.pdf; Accessed June 14th.

24 | Conversation with the author in March 2019

25 | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “The Global Expansion of AI surveillance”; September 17th 2019; https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/09/17/global-expansion-of-ai-surveillance-pub-79847; Accessed June 10th 2020

26 | Wall Street Journal: Huawei Technicians Helped African Governments Spy on Political Opponents; August 15th 2019; https://www.wsj.com/articles/huawei-technicians-helped-african-governments-spy-on-political-opponents-11565793017. Accessed June 12 2020.

27 | Arvind Subramanian: “The Threat of Enfeebled Great Powers“; Project Syndicate; May 6th 2020; https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/covid19-will-weaken-united-states-china-and-europe-by-arvind-subramanian-2020-05?barrier=accesspaylog; Accessed June 14th 2020

28 | Kevin Rudd: “The Coming Post-COVID Anarchy”; Foreign Affairs May 6th 2020; https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-05-06/coming-post-covid-anarchy; Accessed June 10th 2020

29 | Handelsblatt: “Krisenfeste Deutsche: Welche Länder im Corona-Stresstest am besten dastehen“; April 23rd 2020; https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/international/studie-krisenfeste-deutsche-welche-laender-im-corona-stresstest-am-besten-dastehen/25762424.html; Accessed June 10th 2020;

30 | Conversation with the Author in April 2020.