Mapping and recalibrating Europe’s economic interdependence with China

Main findings and conclusions

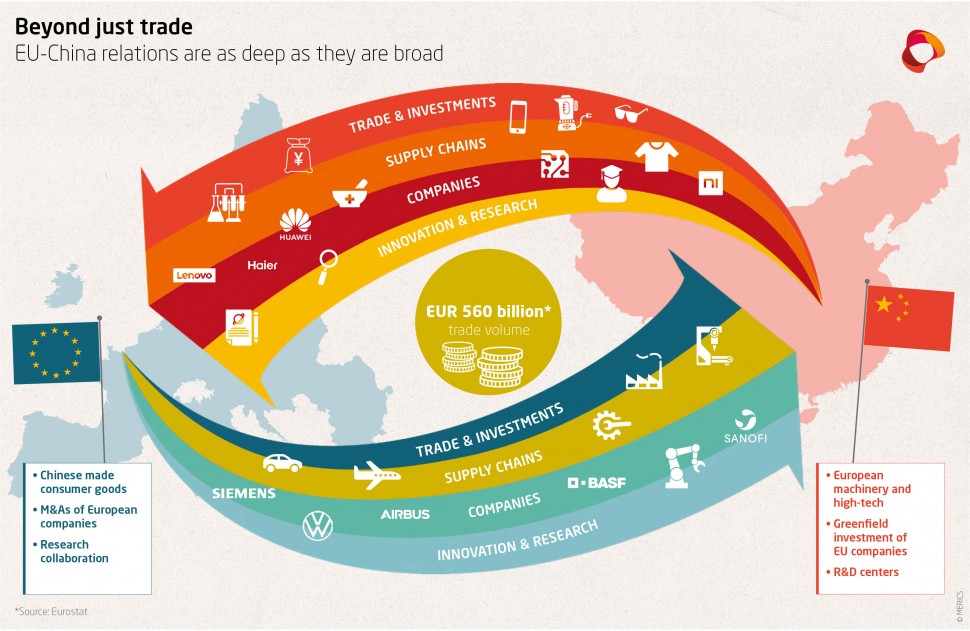

- China’s rapid development and its central role as a driver of globalization have resulted in expanding economic ties with the EU over the past two decades. Between 2000 and 2019, the volume of trade expanded nearly eightfold to EUR 560 billion.

- China is now the EU’s second-most important trading partner behind the United States, bringing in consumer goods and freeing up disposable income for European citizens. At the same time, growing demand for European products made China a crucial export destination.

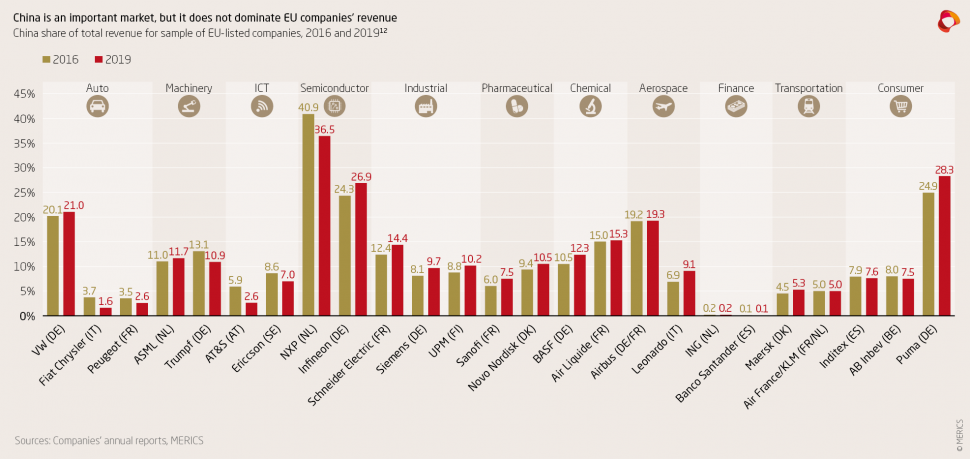

- China’s increasing innovation power and dynamic market shape corporate decisions in Europe – and amplify their exposure to Chinese pressure. However, overall corporate dependence remains limited as markets in Europe and the US are as or even more important than the Chinese market for their business.

- A sample of 25 EU companies from different member states and industries gives an impression of European corporate dependence on China: On average, these companies generated 11.2 percent of their revenue in 2019 in the Peoples’ Republic.

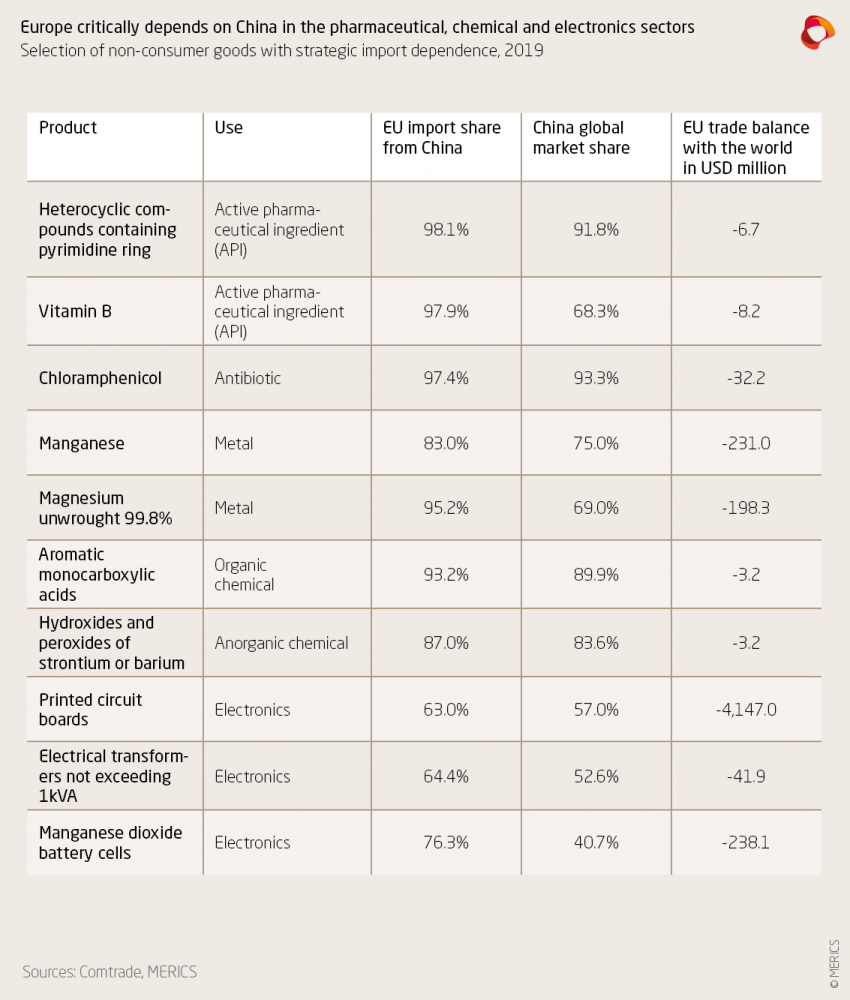

- The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed mutual economic dependencies. Europe critically depends on Chinese imports for the pharmaceutical, chemical and electronics sectors, mostly on components produced in technologically less sophisticated areas of the value chain.

- There are 103 product categories in electronics, chemical, minerals/metals, and pharmaceutical/medical products in which the EU has a critical strategic dependence on imports from China.

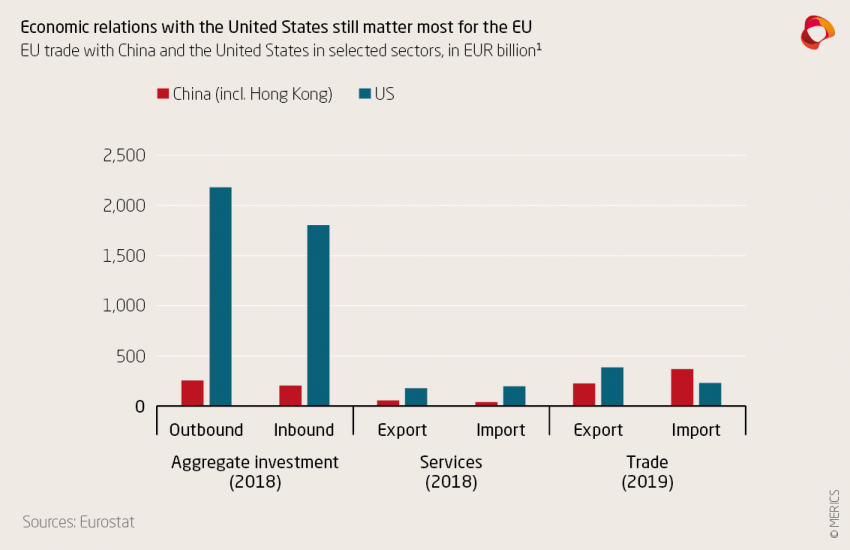

- China’s overall importance for the EU in investment and trade, however, should not be exaggerated either. The presence of Chinese companies and Chinese investments in Europe are still relatively minor, particularly when compared to US actors.

- Economic dependence also cuts both ways: China has much to lose from deteriorating relations with the EU, which is one of the largest foreign investors – and job-creators – in the country, as well as an important market and source of know-how.

- In times of growing political divergence and economic competition with China, EU stakeholders need a clear-eyed assessment of Europe’s economic exposure, vulnerabilities, and strengths to adequately balance the different spheres of cooperation and competition.

- China’s growing ability to engage in economic coercion is a fact, but so far it has been mostly taken the form of threat rather than concrete action. Its policy is selective and pragmatic, taking into account its own economic vulnerabilities.

- The EU’s China policy should not be constrained by an overblown perception of economic vulnerability and build on its relative strengths.

- Preserving a healthy degree of economic interdependence should be in the interest of the EU and China. Strong ties can create opportunities for political exploitation but will also often prevent an escalation.

1. Europe needs a clear-eyed assessment of its economic relations with China

Over the past two decades, the importance of China’s booming economy for European economic interests has grown quickly. Boasting the worlds’ second-largest economy and as an industrial powerhouse with an increasingly wealthy population, the country is now a major trading partner and a key market for the EU.

Economic dependence cuts both ways and can create linkages that the other side does not want to jeopardize. While Europe may rely on China for the likes of protective masks or electronic components, China needs European machinery and specialized equipment to manufacture these goods. However, in times of growing political divergence and economic competition between the two sides, some areas of their economic interdependence are increasingly becoming a matter of concern in Brussels, European capitals, and Beijing. Supply-chain disruptions during the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe have further reinforced fears of overdependence on China.

The EU is currently reevaluating its relations with China. There is a growing realization that deeper integration and potential overexposure come with political risks that could compromise the strategic autonomy of the EU and its member states. And while the EU is reflecting on its vulnerabilities, China is accelerating its efforts towards greater economic and technological autarky. Long-standing unresolved issues with the EU – such as lack of market access, state subsidies, and the expanding reach of the Chinese Communist Party into the economy – are becoming more pronounced as China pushes for more economic self-reliance.

As mutual anxiety about dependence grow, miscalculations on both sides risk severing established globally integrated supply chains. Growing differences are likely to lead to more areas of contestation. Nowadays, European decisions on national security, human rights or geopolitical issues are strongly influenced by concerns over jeopardizing the economic relationship with China. The EU will increasingly be forced to position itself more clearly in defense of its interests – and values.

Against this background, EU stakeholders need a clear-eyed assessment of Europe’s economic exposure, vulnerabilities, and strengths to adequately balance the different spheres of cooperation and competition in its relationship with China. For this, they need to distinguish between three main dimensions.

- First, at the level of national economies, their growing but differentiated asymmetric interdependence with China creates centrifugal forces across and political imbalances in member states that can compromise the EU’s strategic autonomy in geopolitical affairs.

- Second, when it comes to certain critical inputs more specific vulnerabilities can result not only from a lack of diversified supply in crisis situations, but also from strategic dependence with regard to the performance of critical infrastructures and Europe’s defense industrial and innovation base.

- Third, a clustering of corporate or sectoral dependence on China’s market creates risks not only for companies in the face of Chinese strategies aiming at market conditions that effectively limit foreign competition. It can also endanger long-term corporate and national competitiveness if higher value-added and innovation-intensive activities are systematically relocated.

These dimensions can be exploited by China for more targeted economic coercion and corporate lobbying, turning them into liabilities for national and EU policy making. The following sections map and assess interdependence and European vulnerability, and they evaluate China’s political leverage over the EU.

2. China is a key market for the EU but economic dependence remains limited

For many European companies, the Chinese market has been the major growth driver over the past decades. With China’s GDP per capita in 2019 being just around one-third of the EU’s, there is anticipation for even greater potential in further developing economic ties. This section provides a perspective on the EU’s economic dependence on China, considering trade, investment, supply chains, corporate exposure, and innovation.

TRADE AND INVESTMENT DEPENDENCE

China’s rapid development and its central role as a driver for globalization have resulted in rapidly expanding economic ties with the EU over the past two decades. Between 2000 and 2019, the volume of trade expanded nearly eightfold to EUR 560 billion.2 China is now the EU’s second-most important trading partner behind the United States. Imports from China expanded tenfold over the same period, resulting in cheaper consumer goods and freeing up disposable income for European citizens. At the same time, growing demand for European products made China a crucial export destination.

However, China’s overall importance for the EU should not be exaggerated. The presence of Chinese companies and Chinese investments in Europe are still relatively minor. Despite much hype, investments related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) remain small.3 Greenfield investment such as the battery manufacturer CATL’s USD 2 billion German plant or the plans of the energy tech supplier Envision for an electric-vehicle (EV) battery factory in France remain rare. Consequently, Chinese aggregate inbound investment stock remains around 5 percent of the EU’s total. This is dwarfed by the United States, the EU’s largest investment source and destination (see exhibit 1).4

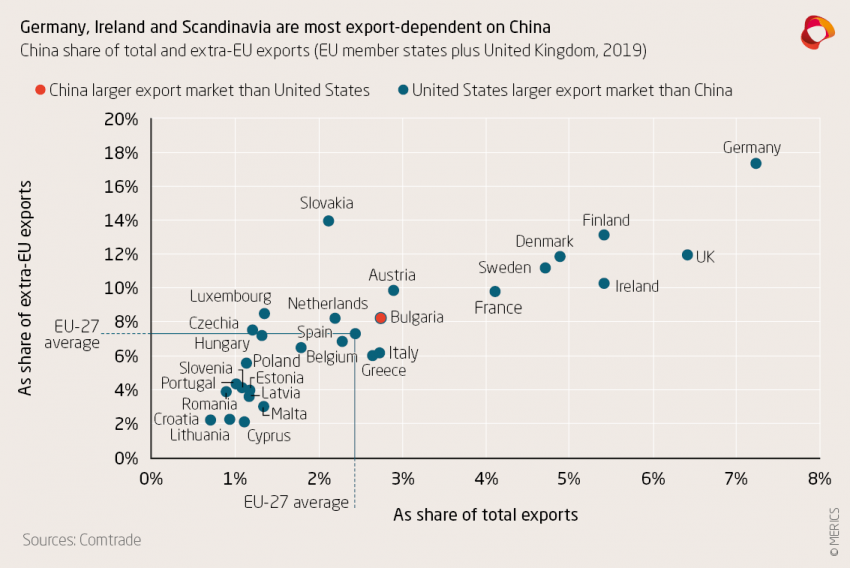

China accounted on average for 2.4 percent of the EU-27 member states’ exports in 2019, compared to 67 percent for the EU single market and 5.7 percent for the United States. Its economic importance greatly varies across member states. China accounts for a higher share of exports for Western European and Scandinavian countries (see exhibit 2). These have also been key investment destinations for Chinese companies over the past 10 years.5

Within the EU, Germany has benefited most economically from China’s rise. Deeper political ties under the leadership of Chancellor Angela Merkel have flanked stronger trade and investment relations since 2005. Germany accounts for 48.5 percent of EU exports to China, 4.6 times more than France, the bloc’s second-largest exporter to China by value in 2019. In the second quarter of 2020, China became Germany’s largest export market for the first time as other major markets, including EU members and the United States, continued to suffer from the Covid-19 pandemic.

But these figures need to be seen in relation to the EU’s overall trade structure. Only 7.2 percent of German exports went to China in 2019. The share of Germany’s exports that went outside the single market was 17.4 percent, far above the EU-27 average of 7.3 percent.

Germany’s flourishing economic relationship with China remains an outlier within the EU. Germany accounts for 31 percent of EU exports to the United States, 17 percentage points below its share of EU exports to China, whereas other members’ exports to the two countries are more balanced. Further, Germany’s US share of extra-EU exports is 21.6 percent, much closer to the EU-27 average of 16.6 percent. Germany’s position as the EU’s manufacturing hub may also contribute to some other member states’ exposure to China being under-represented as they are only indirectly linked to exports through the supply chain.

SUPPLY-CHAIN DEPENDENCE

China’s rise a manufacturing superpower is the result of the shifting of global value chains out of Europe (and other advanced economies) to Asia since the 1970s, and then from within Asia to China since the early 2000s. As the “world’s factory” China dominates many of the product categories the EU imports. For the EU as a whole and some member states, and with regard to specific products, this has resulted in strategic dependence. Strategic dependence is defined here as existing where the EU is a net importer of a good, the EU imports more than 50 percent of that good from China, and China controls more than 30 percent of the global market for that good.6

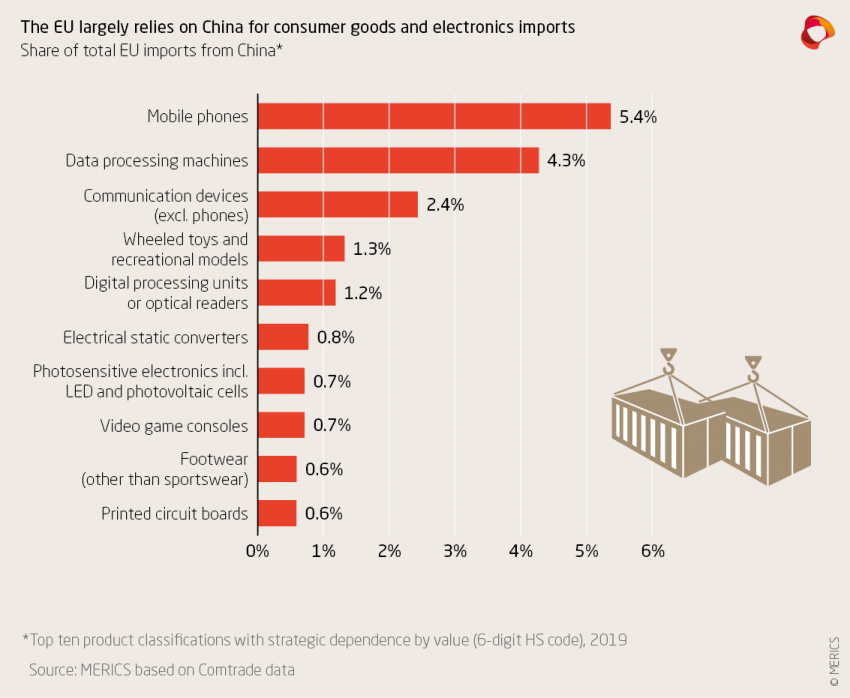

Based on this definition, in 2019 the EU was strategically dependent on China for 659 of the over 5,600 product categories defined by the United Nation’s Comtrade database (see exhibit 3).7 These account for 43 percent of total imports by value from China. Six of the top ten categories are related, at least in part, to consumer products (e.g. textiles, furniture, toys) and consumer electronics (e.g. mobile phones, personal computers, household appliances). However, since they are vital for retail and quality of life but dispensable, any dependence in consumer goods cannot therefore be regarded as critical for the EU.

A critical strategic dependence arises when limited access to a product category can disrupt a country’s economy or leave it otherwise vulnerable. This needs to account for the required technology, know-how, costs, and time required to build up alternative sources for vital industrial production.

Preparedness for shocks is only one factor and trade diversification, not autarky, is the key to the solution. At the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic the EU suddenly became dependent on China for protective masks. With the machinery and materials necessary for their production available in Europe, it was only a question of time until European supply was sufficient and the dependence on China no longer critical.8

Looking beyond shock situations, the EU’s overall critical strategic dependence is limited. There are 103 product categories in electronics, chemical, minerals/metals, and pharmaceutical/medical products in which the EU has a critical strategic dependence on imports from China (see exhibit 4). The vast majority of these are concentrated in technologically less sophisticated areas of the value chain. They are the result of economic choice by companies to reduce costs by relocating production to China.

The EU’s critical strategic dependence on China is most pronounced in the electronics sector. This is not due to the level of technological sophistication involved for these products, but because building up alternative supply chains would be complex and costly. Capable and competitive Chinese producers dominate critical inputs used in upstream production for many industries. This includes essential building blocks for many high-tech electronic products. For example, the most advanced microchip is useless without a proper printed-circuit board (PCB) and accompanying diodes, optoelectronics, or resistors – components that are mainly imported from China.

CORPORATE DEPENDENCE

As a manufacturing behemoth China is already the largest market in many industries (e.g. chemical, plastics, electronics, automobiles) and forecasts continue to be positive for many sectors. China is also on track to surpass the United States as the largest consumer market soon. Given the size of the Chinese market, its importance for many foreign companies has naturally increased – even more so during the Covid-19 crisis, which has left China as the only major market that is growing in 2020.

Looking at a sample of 25 listed EU companies from different member states and industries helps to evaluate European corporate dependence on China for revenue (see exhibit 5). On average, these companies generated 11.2 percent of their revenue in China in 2019, up 0.1 percentage points from 2016. China generated the highest share of revenue for NXP and Infineon (semiconductors), Puma (consumer goods), and Airbus (aerospace). The revenue share for the service-sector companies (finance and transport) was only around five percent, or in some cases insignificant.

It is to be expected that companies supplying China’s demand for high-tech products and those that have built a successful brand will have higher revenue shares from China. However, the fall in revenue share experienced by Ericsson (telecommunication equipment) and AT&S (PCBs) since 2016 shows that the market environment in China can quickly sour for a foreign producer due to political factors and/or rising domestic competition.

With Central and Eastern European countries lacking high-tech and international brands, the Chinese market is mostly irrelevant for their companies, except indirectly through the supply chain of other European countries’ exports.

For most sampled companies, Europe and the United States remain as, if not more, important as the Chinese market. Siemens, a pioneer in cooperating with the government in China, is a case in point.9 China is a key market for the company with a revenue share of 9.2 percent, but it is smaller than the German market (12.3 percent) and significantly smaller than the US one (21.6 percent).

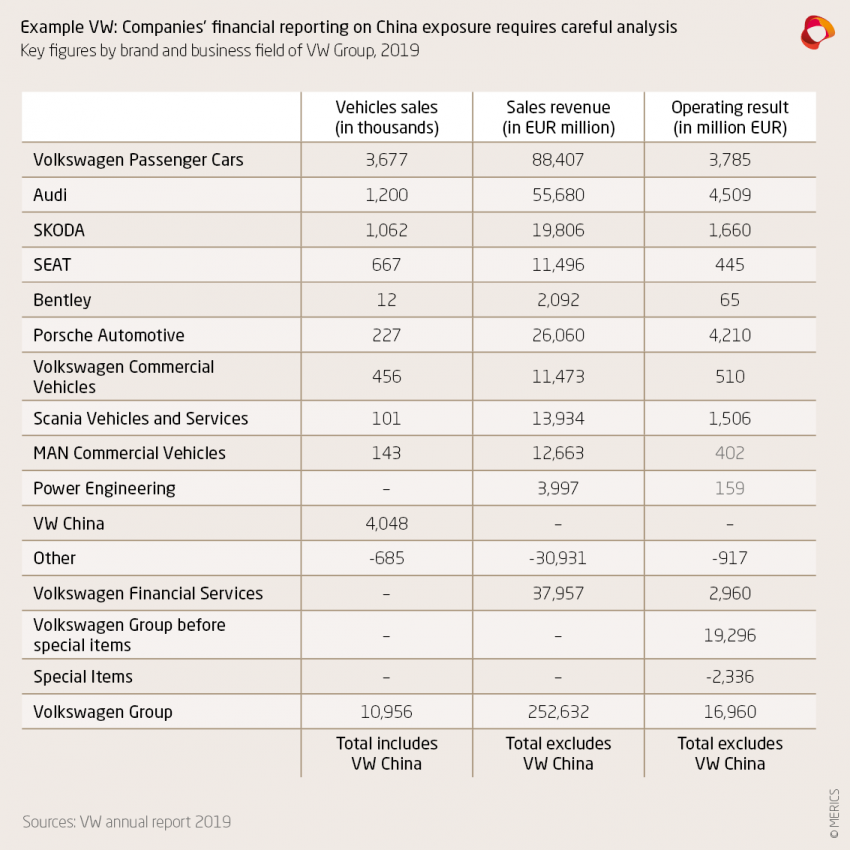

The exposure of the automotive industry to the Chinese market is a key driver of the perception that Germany and Europe are dependent on China. As the world’s largest automotive market, China is undeniably very important for Germany’s industry, including Volkswagen and its suppliers. In 2019, the group’s brands sold 4.2 million vehicles in China, nearly 40 percent of its total vehicle sales, making the country its most important market. Given the slump in other markets due to Covid-19, China’s share of Volkswagen’s sales is likely to rise in 2020.

However, focusing on the number of VW brand vehicle deliveries provides a skewed picture of the group’s dependence on China as it does not account for the ownership structure of Volkswagen Group China, which is owned by VW and its Chinese partners. Ninety-five percent of the vehicles sold in China are produced locally with Volkswagen’s state-owned joint-venture partners (FAW, SAIC, Sinotruk). VW China generates EUR 11.1 billion in profits, of which Volkswagen receives 40 percent, according to its annual report.10

As Volkswagen does not hold a majority stake in VW China, the latter’s sales revenue and profits are not included in the group’s total (see exhibit 6). This makes it very challenging to evaluate the overall importance of the Chinese market for the group. It is estimated here that VW’s China revenue accounts for 21 percent of VW’s global revenue in 2019.11 Its importance for Volkswagen’s shareholders may be considerably higher than that of safeguarding export-dependent jobs in Europe.

INNOVATION DEPENDENCE

China is more than just a market and production hub for European companies. Its innovation power, dynamic market and improved regulatory regime shape corporate decisions that deepen their exposure. China’s government is rolling out the red carpet for research-driven investment, and European companies are willing takers. Foreign companies are tapping into China’s innovation and talent pool by setting up research and development (R&D) centers there, reinvesting large shares of their profits generated in the country.

Of the sampled companies, many emphasize the importance of China for R&D. For example, Sanofi operated three pharmaceutical research centers there, located in Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu, Airbus launched an innovation center in Shenzhen in 2019, and Siemens operates 20 Chinese R&D centers, which include its global headquarter for robot research.

European companies are also increasing their stakes in Chinese companies where they can. In 2020, this has been particularly evident in the electric-vehicles sector. Most notably, Volkswagen acquired a majority stake in the e-mobility joint venture JAC and a 26 percent stake in the EV battery supplier Gotion High Tech.

The rapid developments in emerging technologies make it essential for European companies to be present in the Chinese market. In areas ranging from autonomous driving to e-mobility, smart manufacturing and digitization, China is quickly evolving as a lead market and is a vital testing ground.

3. It cuts both ways: China has much to lose from deteriorating relations with the EU

Opening up to foreign suppliers and investments has not only catalyzed a period of rapid economic development for China; it has also resulted in greater interdependence with Europe. If relations between them deteriorate due to growing political disagreements, China like Europe would suffer considerable economic consequences.

TRADE AND INVESTMENT DEPENDENCE

Despite technological advances China remains the “world’s factory.” Exports are less important for its economy but still accounted for 18.4 percent of GDP in 2019. The EU accounted for almost 20 percent of China’s exports last year. For most EU countries imports from China outstrip exports, which is largely due to its dominance in manufacturing of consumer-related goods and electronics. In 2019, China had a trade deficit with only 20 of its trading partners, all except South Korea, Switzerland, and Singapore exporters of raw materials or commodities (see exhibit 7).

The EU is one of the largest foreign investors - and job-creators- in China with a heavy focus on greenfield investments, building new factories, opening new offices or R&D facilities.13 In 2019, Volkswagen reinvested 90 percent of profits generated in China in the country, mainly in the e-mobility sector, BASF broke ground on a USD 10 billion project in Zhanjiang in Guangdong Province, and the Danish chemical company Hempel started building a EUR 100 million factory in Shandong.

German companies directly employ over 1 million staff in China.14 Volkswagen operated 26 production facilities in China directly employing over 100,000 people in 2019.15 Each factory will likely require other automotive suppliers to follow suit and open additional facilities of their own in the vicinity.

In addition, many European brands, from consumer goods to electronics, have outsourced production to contract manufacturers in China. Labor-intensive mass production remains vital for China’s economy, and Chinese factories employ millions churn out consumer goods that are bought by European retailers. For example, the Spanish textile giant Inditex purchases much of its merchandise from over 1,300 factories employing more than 400,000 workers in China.16

Investments by European companies are essential for China’s economic development. Not only do they contribute to meeting the government’s goals of industrial upgrading and employment, they are a key generator of local tax revenue. This is especially the case in China’s main economic centers in the Bohai Region and in the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas where there is a heavy presence of European companies. But investments contributing to the development of the Western provinces or in the “rustbelt” in the Northeast are equally important.

SUPPLY-CHAIN DEPENDENCE

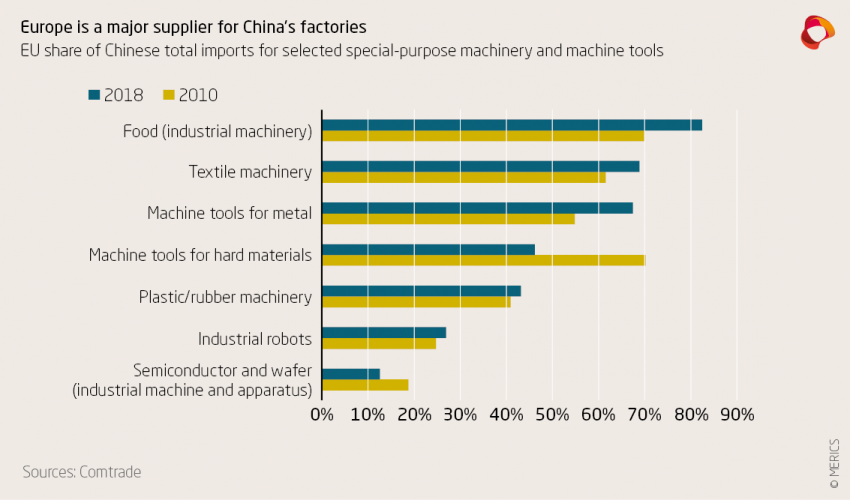

The strategic import dependence in some parts of supply chains is mutual. European machinery, specialized instruments, materials and components are crucial for China’s manufacturing strength not only in low-tech but increasingly also in high-tech. For example, access to the Dutch semiconductor equipment manufacturer ASLM is vital for China’s ambitions to build up a competitive semiconductor industry. Production of consumer goods requires European-made plastic injection or textile machinery (see exhibit 8).

The strength of EU companies comes from their higher degree of specialization as well as from occupying niche markets. For some European machinery manufacturers, especially smaller ones, this means their relative dependence on the Chinese market is matched by China’s need for their technology to build competitive production.

China’s dependence on traditional European high-tech industries, such as machinery, is much greater. Finding domestic or foreign alternatives to Europe for advanced machinery is more difficult than for final products such as protective masks or consumer goods. This is why building up tech autarky and reducing dependence on foreign technology are at the heart of Chinese industrial policy. But, despite much progress, this remains a difficult, costly and time-consuming effort.

CORPORATE DEPENDENCE

With improved innovation and product quality, Chinese brands like Lenovo, Hai-er, DJI, or Alibaba have become household names in Europe. Huawei, Xiaomi and, recently, Vivo are expanding their presence in the European smartphone market. Huawei and Lenovo generated nearly a quarter of their revenue in the Europe, Middle East and Africa region, with the EU accounting for at least 50 percent.17 This indicates the European market is almost as important for Chinese companies as the Chinese market is to the sampled EU companies.

Even big Chinese corporations still tend to largely produce in China while their international manufacturing activities are still underdeveloped (although they also have international supply chains). Meanwhile, the countless export-oriented small and medium sized enterprises in the major export hubs in Guangdong, the Yangtze River Delta and Fujian rely heavily on the European market.

Chinese companies’ investments in Europe have focused more on mergers and acquisitions than on building up new manufacturing capacity. Despite recent adjustments in investment screening, Europe remains fundamentally open to Chinese investors and its technologies available to them. Although Chinese investments in the EU dropped by 33 percent in 2019 compared to the previous year, Chinese companies continued to invest in tech-related sectors. In 2019, the information and communications technology (ICT) sector remained the top sector in terms of number of transactions, accounting for 20 percent of all the total.18

Chinese companies are still in the early stages of internationalization, but the list of truly international ones can be expected to grow.

INNOVATION DEPENDENCE

Chinese companies and research organizations rely on foreign know-how, which remains indispensable for building up the country’s domestic innovation system. This is especially the case where technological capabilities are lagging, such as semiconductors or basic research. China gains from European companies expanding their R&D in the country, but access to know-how abroad is still vital. It therefore benefits from the fairly unrestricted access it has to Europe.

Next to mergers and acquisitions in Europe, another important element is research collaboration with European companies, universities or research organizations.19 This is reflected, for example, by the increasing number of Chinese students at European universities. In 2015, the EU attracted 24 percent of Chinese students studying abroad.20

As they become more international, Chinese companies also set up R&D centers in Europe, trying to tap into local knowledge. For example, Geely opened an EV research center in Germany in 2019, while Huawei has established 5G innovation centers in collaboration with European telecommunication carriers and maintains cooperation with 140 European universities and institutes.21

4. Killing the chicken to scare the monkeys: China’s strategy to leverage bilateral economic ties

The focus of European decision makers on economic ties with China and a growing perception of dependence has enabled China’s government to instil in Europe the assumption that friendly political relations are necessary for good economic relations. From this perspective, only if European governments or companies act in accordance to its political expectations can they expect economic rewards in the form of investments (e.g. as part of the BRI) or improved market access.

However, although they have surged in 2019 and 2020, Chinese threats to inflict economic pain on Europe are seldom more than rhetoric.22 Apart from a ban on Norwegian salmon in 2010, Europe has rarely been affected by actual economic coercion.23 There are, however, well-documented cases of China discouraging European governments from speaking up, let alone acting, on issues that matter to it related to the rules-based international order (e.g. with regard to the South China Sea and Taiwan) or human rights.

For example, in 2016 Greece and Hungary obtained the watering down of an EU statement on the upholding of the South China Sea ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, while in 2017 Greece opposed an EU statement on China’s human rights record and Hungary abstained from signing a joint EU statement in the UN Human Rights Council on the alleged torture of human rights lawyers in China. Both EU members were also early to embrace the BRI and the 17+1 cooperation format between China and Central and Eastern European countries.

European companies also stay silent or plead ignorance on sensitive issues for China. For example, in 2019 Volkswagen’s CEO has claimed not to be aware of the situation in Xinjiang.24 In another case, the French cosmetic giant Lancôme canceled a concert by the Hong Kong pro-democracy singer Denise Ho in 2016 after online calls for a boycott of the company in mainland China.25

It is still an open question if the mix of the occasional “wolf warrior” rhetoric, nationalistic online uproar or boycotts will help China to get the message across. For example, it is unclear if the implied threat by China’s ambassador to Germany, Wu Ken, in 2019 targeting the German automotive industry should Huawei be banned as a 5G provider had an impact on decision making in Berlin.

What will matter more than highly visible Chinese threats and any reported direct effects is preemptive obedience on the European side: tacit alignment and strategic reorientation taking place behind closed doors. Most European actors understand Chinese sensitivities very well and often adjust their behavior accordingly without an actual threat being expressed by the Chinese side. The more EU member states prize the deepening of profitable economic ties with China, the more likely this strategy will be successful in the future.

5. Calling the bluff: The EU has little to fear when speaking in one voice

In its engagement with the EU, China continues to focus on weak links, in the expectation that it will not be able to respond in a coordinated way. It is to its advantage if there is no cohesive EU China policy and if member states compete with each other to attract economic opportunities.

The economic interdependence between EU and China is undeniable. At the same time, the EU will increasingly need to make strategic decisions in its relationship with China, given the growing incompatibility between their political and economic systems. This does not mean severing ties and fostering a decoupling process. In-stead it requires managing interdependence and rebalancing the relationship.

The EU’s China policy should not be constrained by an overblown perception of economic vulnerability and build on its relative strengths. China’s willingness and growing ability to engage in economic coercion is a fact, but so far it has been mostly taken the form of threat rather than concrete action. Its policy is not only selective but also pragmatic, taking into account its own economic vulnerabilities.

Some EU members are slowly starting to realize that China does not have that much economic leverage over them. When Prague cancelled its sister-city agreement with Beijing in 2019 and the speaker of the Czech Senate led a delegation to Taiwan in September 2020, China threatened Czech economic interests but, so far, it has only taken symbolic steps such as cancelling concerts in China or not sending a Panda to Prague’s zoo. China could escalate and impose economic costs if similar actions were conducted by a representative of the Czech government rather than of parliament or of a municipal administration. Given the limited interlinkages between the two countries, however, it would be difficult to apply economic leverage.

While China clearly could inflict economic pain on countries in Western Europe and Scandinavia, any measures it takes would need to be targeted at strategically irrelevant “scapegoats.” Companies supplying China with specialized technology will not be touched as long as it has limited – and, more importantly, no domestic – alternatives. In an example from Asia, South Korea’s retailer Lotte was forced out of China in 2017 following the installation of US missiles on land it previously owned in its home country.

A key factor for how effective China could be in leveraging economic ties for strategic purposes will be peer learning and the success of collective action in Europe. European countries have a lot to learn from Chinese bans that affect-ed Australian, Japanese and South Korean economic interests. Recent examples in Australia highlight the selective nature of China’s economic coercion, which aims to minimize economic costs to itself.

East Asian advanced economies have also shown that a more strategic stance on China is possible without necessarily doing harm to interdependence. Japan and Taiwan have, for instance, effectively banned Huawei from the rollout of their 5G networks. In contrast to the heated reactions from Chinese representatives in Europe on this issue, the response was fairly muted. Issues of national security are much more present in East Asia’s relation with China, a reality the Chinese leadership is aware of and seems, in a way, to accept.

Should China pressure even just a few highly exposed EU member states or companies, this could backfire. The EU could retaliate by targeting comparable Chinese economic interests. The escalating Sino-US decoupling should be a warning to both sides of how quickly things can spiral out of control.

When it comes to defending its economic interests, the EU is already changing course. Recent proposals for a new trade-defence instrument or solidarity mechanisms aimed at protecting EU economies from other countries’ coercion show the way forward.26

Preserving economic interdependence should be in the interest of the EU and China. Strong ties create opportunities for political exploitation but will also often prevent an escalation. The EU, its member states, and companies will, however, increasingly need to take into account the systemic differences with China and its willingness to leverage economic linkages for strategic purposes. This requires a more clear-eyed consideration of long-term national security interests. Consequently, the EU needs to assume a more resolute and unified position to provide the necessary political flanking for its economic relationship with China.

- Sources

-

1 | Investment data includes data from Hong Kong. Chinese in and outbound investment flows are often channeled through Hong Kong and can distort data. Chinese investment stock is also likely to be underrepresented due to use of offshore financial centers.

2 | European Commission – Countries and regions: China. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/china/. Accessed: October 14, 2020.

3 | Eder, Thomas and Mardell, Jacob (2018), “Belt and Road reality check: How to assess China’s investment in Eastern Europe”, MERICS. https://merics.org/de/analyse/belt-and-road-reali-ty-check-how-assess-chinas-investment-eastern-europe. Accessed: October 22, 2020.

4 | European Commission – Countries and regions: USA. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/united-states/#:~:text=Either%20the%20EU%20or%20the,third%20of%20world%20trade%20flows. Accessed: October 14, 2020.

5 | Kratz, Agatha, Huotari, Mikko, Hanemann Thilo, and Arcesati, Rebecca (2020). “Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update”, MERICS. https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2019-update. Accessed: October 29, 2020.

6 | This study replicated, with some adaptation, the methodology used by the Henry Jackson Society: https://henryjacksonsociety.org/publications/breaking-the-china-supply-chain-how-the-five-eyes-can-decouple-from-strategic-dependency/. Accessed: July 20, 2020.

7 | The product categories reflect the classification of the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS codes) by the World Customs Organization on a six-digit level. This allows for a granular analysis of traded goods.

8 | Financial Times (2020). “Scramble for masks sees demand soar for Germany’s golden fleece”. https://www.ft.com/content/b26e82b8-97ab-495b-a0ab-203708868f9b. Accessed: May 29, 2020.

9 | See corporate information on Siemens China on the company’s website: https://new.siemens.com/cn/en/company/about/siemens-in-china.html. Accessed: October 7, 2020

10 | Volkswagen (like nine other companies in the sample) does not publish its sales revenue in China. This is standard accounting practice as the company operates with local partners and hence will only report the proportionate profits based on the 40 percent stake VW holds in its joint ventures.

11 | The sales revenue is estimated using per unit sales revenue for different brands as stated in the annual report. The revenue of the vehicles exported to China are accounted for by 100 percent, while the locally produced vehicles revenue share is in proportion to the 40 percent equity stake VW holds in the VW China Group.

12 | The revenue share from China for Volkswagen, Peugeot, NXP, BASF, Air Liquide, Airbus, Leonardo, Air France/KLM, Inditex, and AB Inbev was not published separately in annual reports. It was therefore estimated using other China-related information provided in the annual reports.

13 | Kratz, Agatha, Huotari, Mikko, Hanemann Thilo, and Arcesati, Rebecca (2020). “Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update”, MERICS. https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2019-update. Accessed: October 29, 2020.

14 | German Chamber of Commerce in China (2015). “German Business in China - Business Confidence Survey 2015”.

15 | See corporate information on Volkswagen China on the company’s website: https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/de/volkswagen-group-china-5897. Accessed: October 14, 2020.

16 | See Inditex annual report 2019: https://www.inditex.com/investors/investor-relations/an-nual-reports. Accessed: August 5, 2020.

17 | Breakdown taken from companies‘ annual report, no further information on revenue share for the EU. Huawei: https://www.huawei.com/en/annual-report/2019 and Lenovo: https://investor.lenovo.com/en/publications/reports.php. Accessed: October 8, 2020.

18 | Kratz, Agatha, Huotari, Mikko, Hanemann Thilo, and Arcesati, Rebecca (2020). “Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update”, MERICS. https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2019-update. Accessed: October 29, 2020.

19 | For more detailed information MERICS publications: https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2019-update and https://merics.org/en/report/evolving-made-china-2025. Accessed: August 9, 2020.

20 | China Daily (2019). “Europe opens its arms to Chinese students”. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201906/19/WS5d09d5c2a3103dbf143291cc.html#:~:text=According%20to%20official%20statistics%2C%20more,of%207.5%20percent%20from%202014. Accessed: September 20, 2020.

21 | See Huawei annual report 2019: https://www.huawei.com/en/annual-report/2019. Accessed: October 8, 2020.

22 | Hanson, Fergus, Currey, Emilia and Beattie, Tracy (2020). “The Chinese Communist Party’s coercive dimplomacy”. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/chinese-communist-partys-coercive-diplomacy. Accessed: September 8, 2020.

23 | The Chinese ban came in response to the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to Liu Xiaobo.

24 | BBC (2019).” VW boss ́not aware ́ of China’s detention camps”. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/business-47944767. Accessed: September 14, 2020.

25 | BBC (2016). “ Lancome cancels concert after Chinese online backlash.” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-36457450. Accessed: September 14, 2020.

26 | See European Commission White Paper on foreign subsidies in the Single Market (June 2020): https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1070 and Executive Vice-President Vladis Dombrovskis ́ hearing on trade portfolio at the European Parliament (October 2020): https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20201001IPR88310/hearing-of-executive-vice-president-valdis-dom-brovskis-on-trade-portfolio. Accessed: October 28, 2020.

This study was supported by a Ford Foundation grant and is licensed to the public subject to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.