Growing US-China rivalry in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia: Implications for the EU

Key findings and conclusions

- Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America are key regions in the broader contest for global primacy between China and the United States. It is vital for the EU’s interests in the three regions, as well for its ties to the United States and China, to understand the full dimensions of their rivalry.

- Among the three regions, the US-China rivalry is most intense and comprehensive in Southeast Asia. Some countries in the region have become critical of Beijing’s growing assertiveness, while China has increasingly proven willing to use economic leverage to pursue its interests. In the US administration’s regional agenda, security and defense cooperation has become more prominent in competition with China.

- Africa has provided the best fit for and has been the most receptive to China’s development-focused economic diplomacy. China claims a historic solidarity with developing countries in the region, which has bolstered intensified trade, investment, and financial relations. The Biden administration currently focuses competition with China in the region on infrastructure, technology and health governance.

- China’s role in Latin America is mostly defined by commodity trade and investment. Its economic and political influence in Latin America will be only as strong as its commodity-based links to the region. Yet, given that the United States has frequently been a fickle partner for Latin American countries, their government and business leaders will continue to look for alternatives.

- Heightened US-China competition in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia is a key feature of the new era of great-power rivalry. There are important implications for the EU:

- In Southeast Asia, the EU needs to establish for itself a central role in providing alternatives to China in the economic, technology, connectivity and governance spheres.

- In Africa, the EU should leverage its proximity and existing economic and societal links to build genuine partnerships.

- In Latin America, the EU should build on its long-standing as well as more recent economic and cultural ties to provide sustainable, long-term cooperation as the region rebuilds after the Covid-19 pandemic.

1. The renewed US-China rivalry and its legacy

The Biden administration came into office at the start of 2021 embracing the language of “extreme competition” with China. Yet the rise of strategic rivalry between the United States and China had already intensified over previous years. This has become especially acute in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. This new era of US-China rivalry is important for all of those affected by its multiple dimensions, including the European Union, which in 2021 introduced major proposals for a Global Gateway strategy to promote infrastructure and connectivity development as well as an Indo-Pacific strategy to expand its role in Asian economic, security, and governance.

As the United States and China have increasingly perceived and portrayed their highly interdependent relationship as a source of vulnerability and concern, they have each sought to shore up their economic, technological, and geopolitical interests and security while also seeking new sources of competitiveness across the board. While the bilateral elements of their expanding rivalry have been analyzed in great detail, how this has played out in regions like Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia is equally important.

This monitor looks at the rising US-China rivalry in these three regions, drawing lessons that might not be apparent if the focus were only on one. In addition to analyzing the way the United States and China frame and portray their relations with countries in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, it explains some of the ways these countries are responding to their increasing rivalry.

The rivalry between the United States and China in these regions is part of their broader contest for global primacy. Many US officials are convinced of China’s ambitions to wrest this from Washington, with more or less success and impact on US interests in each of the regions. For their part, Chinese officials are just as convinced of the United States’ commitment to maintain its hegemony in these regions while undercutting China’s expanding economic and political relations with them. For their part, Chinese and US businesses engage in broad and intense economic competition in these regions—sometimes in ways that overlap with the strategic aims of their country’s government, sometimes undercutting or complicating them.

For the EU’s interests in the three regions, as well for its ties to the United States and China, understanding the full dimensions of their rivalry is vital. EU interests in Southeast Asia, within a broader focus on the Indo-Pacific, and in Africa are especially impacted. The US-China rivalry in Latin America also impacts the EU’s economic and political interests there.

2. A framework for understanding the dimensions of 21st century US-China rivalry

In Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, the new US-China rivalry includes a mix of recent elements and Cold War legacies. In all three regions, it ranges from competition for economic and technological opportunity and influence on military and geopolitical rivalry as well as longer-standing pursuits of status and prestige.

The legacy of Cold War rivalry is especially clear in how China portrays its relations with the three regions. Despite the dramatic differences between the domestic and foreign policies of the Mao era and those of today, its leaders stress the continuity in China being a reliable partner that shares common goals and values with countries in these regions. While they no longer emphasize revolutionary solidarity, they point to China’s role in supporting their economic development.

Since the early 2000s, China has highlighted its economic progress to promote itself as a leader and agent of development on the global stage, especially in the three regions. Its leaders explicitly draw on Cold War legacies of Third World friendship as they argue that contemporary development partnerships underpin the country’s competitive advantage there.

The United States has also built on Cold War legacies in its recent rivalry with China. Noting fundamental differences in the two countries’ political, economic, and ideological systems, US officials have underscored that today’s situation is a continuation of the clash between Western political and economic liberalism and Chinese communism. In Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, the United States raises points that were also a feature of its Cold War rivalry with China (and of the US-Soviet one): warning that a communist-led political system and state-dominated economy offer a model inferior to democracy and free markets.

Yet, if they draw on Cold War legacies to support their claim to be a preferred economic and diplomatic partner for countries in the three regions, China and the United States do so in ways and across dimensions that are distinct from that era. Much of their contemporary rivalry, increasingly framed as “competition,”2 is playing out in three interconnected arenas.

In connectivity, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has increasingly elicited not just criticism but also the beginning of a response by the United States (including with its allies and like-minded partners in Asia and Europe). In technology, US and Chinese officials and firms vie for government and market partnerships. Last, and with some overlap with the other two arenas, the United States and China increasingly compete to become preferred models and partners in these regions in the critical areas of health and climate governance.

Three periods stand out in the evolution of this rivalry:

- the Cold War, especially from the 1950s until Mao’s death in 1976

- the early 21st century “boom” in China’s relations with developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America

- China’s more assertive, development-based foreign policies under Xi Jinping, most obviously symbolized by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

2.1 Southeast Asia: US-China rivalry at its most extreme

Among the three regions, the US-China rivalry is most intense and comprehensive in Southeast Asia. The region is at the heart of China’s “neighborhood” or “peripheral” diplomacy but presents it with a complex mix of challenges and opportunities given long-standing historical, geopolitical, and cultural connections.

Southeast Asia was at the core of the efforts of the Peoples’ Republic China (PRC) in the years following its founding to present itself as a partner and leader in socialist, revolutionary post-colonialism (including as part of Zhou Enlai’s diplomacy emphasizing Afro-Asian solidarity). Those efforts, and subsequent military conflict with neighboring, Communist-led Vietnam in 1979, revealed some of the difficulties China faced in forging a leadership role among its smaller Southeast Asian neighbors.

In the late 1990s, China embarked on a diplomatic charm offensive in Southeast Asia, in part to reassure neighbors wary of its rise.3 Chinese officials sought to convince countries in the region that the country’s growing economy and impact would be mutually beneficial, including by providing them with a wide range of trade, investment, and development opportunities.

However, by 2009, and especially in the wake of Chinese maritime military and commercial provocations in the South China Sea, some countries in the region (as well as the United States) were criticizing Beijing’s growing assertiveness. As the likes of Myanmar tried to reduce their economic and diplomatic overdependence on China and moved toward closer ties with the United States and Europe, and as Washington promoted its nascent pivot to Asia, Beijing changed tack. It attempted to reassure Southeast Asian countries of the benefits of closer economic ties by doubling down on policies, like the BRI, meant to deepen commercial interdependence with China.

Chinese officials emphasized claims that economic development—largely measured by growing volumes of trade and investment and financial opportunities with China—was fundamental to ensure regional stability and peace.

The Association of Southeast Asian state (ASEAN) is expected to form the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2030, following the United States, China, and the EU. The region’s economic links to China and the United States reflect deep interdependence. ASEAN is already the fourth-largest export and import partner of the United States, behind Canada, Mexico, and China. It surpassed the EU as China’s largest trade partner in 2020, partly as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, while China has been ASEAN’s largest trade partner since 1999.

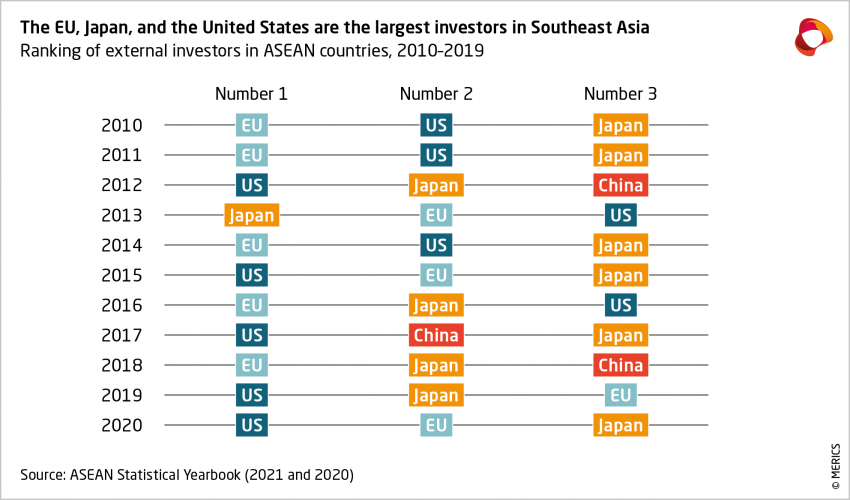

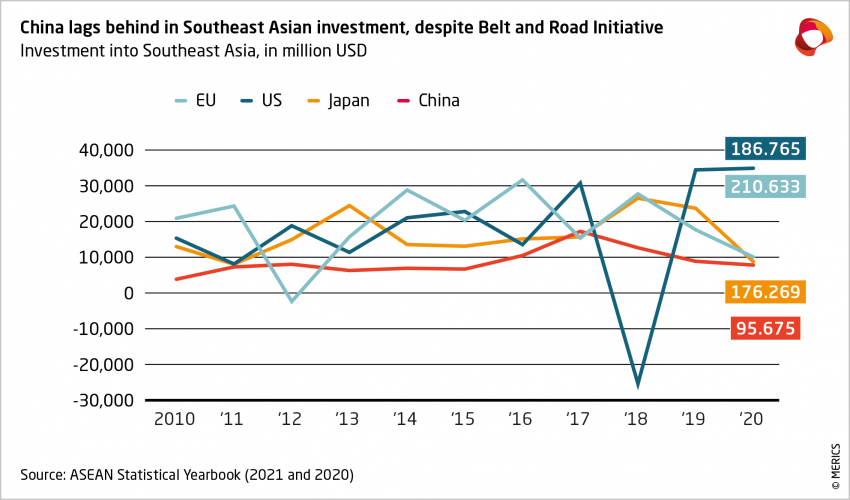

The investment picture is more mixed. Despite popular perceptions, China is not the largest (or the second- or third-largest) source of investment for most countries in Southeast Asia. Japan, the EU, and the United States continue to have the largest stocks of foreign direct investment in the region.4 Yet China’s role as an investor in the region has increased dramatically in the last two decades, mostly on the back of energy, mineral, and infrastructure deals.

Despite their important economic links, China is far from dominant in Southeast Asia, in the sense of being able to dictate to countries or to maintain clients there. There are exceptions, like Cambodia or Laos where China has major diplomatic, economic, and military ties. But, in general, countries and businesses in the region seek to gain maximum benefit from China’s economy but also to hedge against the country being overly dominant in political or military terms (including when it comes to disputed territorial claims in the South China Sea).

At the same time, though, China has increasingly proven willing to use economic leverage, through coercion and inducements, to pursue its interests. Examples of coercive trade measures—tied to political and diplomatic spats—have included restricting exports of rare earths to Japan, the flow of Chinese tourists to South Korea, and the import of coal from Australia and of bananas from the Philippines.

For the United States, Southeast Asia was a key region for rivalry with China during the Cold War. The most obvious example of indirect and direct confrontation between them was the Vietnam War (from the early 1960s to the early 1970s). In the early post-Cold War era (the 1990s), the United States treated Southeast Asia with “benign neglect,”5 and it was more concerned about financial crises in the region (particularly in 1997) than about overt competition with China.

The Obama administration re-engaged with the region as part of its broader pivot or rebalance to Asia. This was at least partially motivated by rivalry with China. With the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), it sought to lead an economic initiative that did not include China but that was constructed with setting the trade and investment standards with which Chinese firms would have to operate in mind.

The TPP was at least indirectly aimed at setting trade rules in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in Asia that were more closely aligned with US than Chinese interests. The rebalance included a heightened military focus, including the 2014 Force Posture Agreement with Australia, on China’s increasingly assertive maritime posture in the South China Sea.

At the same time, the United States engaged in direct geopolitical competition with China for influence in Southeast Asia. The most prominent example was the normalization of diplomatic ties with the newly democratic government of Myanmar after 2011, which was seen as a diplomatic setback for China.

The Trump administration rejected the TPP, which was the main economic component of the rebalance. At the same time, it introduced a new, largely security-focused emphasis on a “free and open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP), a concept first outlined by Japan under Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. The administration’s emphasis on the FOIP included a clear focus on the perceived threat posed by China in Southeast Asia, including in maritime disputes in the South China Sea, but it came also in response to China’s BRI and its deepening economic interdependence with ASEAN. The Trump administration also argued that China was a malignant actor with increasing influence in the region.

The Biden administration has maintained certain Trump policies and introduced new ones. It emphasizes the Indo-Pacific, and Southeast Asia in particular, as a region where it and its allies and partners can and should compete more effectively with China. Like its predecessor, it has emphasized military cooperation, including in the South China Sea (for example, with the AUKUS security pact with Australia and the United Kingdom) more than economic or trade initiatives.

The United States joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (the reformulated version of the TPP) appears to be a non-starter for the administration. In part this is because of the recent bipartisan consensus in the United States that trade deals have strengthened China’s hand while leaving American workers less well-off.

The Biden administration has also put more emphasis on US-led infrastructure cooperation, including in Southeast Asia, to counter the BRI. Recently, in an overview of its draft Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the administration said it would initially focus on “trade facilitation, digital economy standards, supply-chain resiliency, infrastructure, decarbonization and clean energy, export controls, tax and anti-corruption.”6 One expanding arena of rivalry with China in Southeast Asia is US assistance to governments in the region to build technical and legal capacity to evaluate and structure Chinese investments and loans.7

Yet, despite the above, security and defense cooperation has been more prominent than economic (including trade) measures when it has come to the Biden administration’s regional agenda for competing with China. For example, cooperation with Australia in nuclear-submarine technology has been the cornerstone of its efforts with allies in the region.

Overall, while the US-China rivalry in Southeast Asia has deep historic roots and covers a comprehensive array of issues and countries, some key trends have emerged. In terms of connectivity and technology, the region is at the heart of the maritime and continental versions of the BRI. This includes not only traditional transport infrastructure like railways but also energy and digital infrastructure, such as for electronic payments and smart-city technology. In attempting to forge a competitive response, the Biden administration is pursuing cooperation with partners in the region to offer higher standards in terms of financing and environmental quality through its Build Back Better World (B3W) and Blue Dot Network schemes.

In the months and years ahead, China and the United States will also increasingly focus on the quality and size of their respective contributions to the region’s health and climate challenges. Countries such as Myanmar and the Philippines will be at the heart of the US-China rivalry as they grapple with their economic, social, and governance challenges and their broader geopolitical alignments.

For Europe, the US-China rivalry in Southeast Asia creates opportunities as well as risks. The region is a key trade and investment partner and its economic dynamism, as well as potential volatility amid this rivalry, will require ever-greater European competitiveness and understanding of regional dynamics. Managing supply chains in the region, including as a hedging strategy against overdependence on Chinese, will be one of the key challenges European firms and governments face in the years ahead.

One of the greatest opportunities for Europe in Southeast Asia arises from its potential to be an advocate for high-standard, rules-based, and practical approaches to issue areas that are most contentious and polarized in the US-China relationship: connectivity, technology, and health and climate governance. Its Indo-Pacific and Global Gateway strategies reflect a recognition of the importance of Southeast Asia to the EU, but for these to live up to their aims will require implementation that highlights that European firms and public policies offer viable, attractive alternatives amid the growing US-China rivalry.

2.2 Africa: Competition over development partnership

Of the three regions, Africa has provided the best fit for and been the most receptive to China’s development-focused economic diplomacy. In part this is because Chinese officials have worked assiduously to build on Mao-era legacies of post-colonial, Third World leadership and solidarity in the region. While building on long-standing diplomatic themes like China’s avowed commitment to non-interference, Chinese officials have also emphasized specific 21st century elements of the relationship, which are meant to bolster China’s claims to being a uniquely appropriate development partner for African countries (with implicit or explicit comparisons with the United States).

China’s reinvigorated trade links to energy- and mineral-rich countries in Africa in the mid-to-late 1990s and early 2000s helped set the stage for a wave of high-level diplomacy as well as well as more varied types of investment and lending relations with countries in the region. Building on these booming commercial and diplomatic ties, and as encapsulated in white papers on the region in 2006 and 2015, China has also actively fostered regional multilateral dialogues.

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) provides a regular setting for high-profile demonstrations of diplomatic cooperation, including displays of Chinese largesse, and a way for China to pursue region-wide discussions or negotiations when bilateral ties are seen as insufficient or contrary to its interests.

Overall, for the last two decades, Africa has been at the heart of China’s approach to developing countries, including since 2013 with a central role in the BRI. China’s development-themed economic diplomacy in Africa includes elements of direct or indirect competition with the United States and the West, in particular by claiming that its primary method of development cooperation is based on enhanced trade, investment, and financial links as opposed to a paternalistic “development-as-aid” models preferred by the United States and OECD countries. China has been keen to emphasize that it is a good development partner because it is willing to do business with African partners in a way that other countries are not. However, the EU remains a larger trade partner for many countries in the region.

China’s development-themed economic diplomacy—presented as being win-win—has not been without controversies, criticism, and challenges in Africa. This includes anxiety about the unsustainability of commodity-dependent trade ties, nontransparent or unsustainable lending, and harmful environmental impacts.

China’s engagement with African countries has varied. One major reason for this is that its policy-bank lending for infrastructure megaprojects had already been in decline for some years prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, which exacerbated the trend. The value of Chinese imports of key African raw materials also decreased considerably in 2020 and 2021. But such pressures dampening trade and financial relations are only part of the story.

Recent years have also seen more cooperation in the creation of special economic zones in Africa and of Chinese-backed legal institutions focused on investment-dispute resolution. There has been also a state-backed push by China into the health and technology competition with US and Western firms.

The United States has increasingly been critical of China’s role in Africa. Here too, the roots of their rivalry there reach back to the Cold War. In the 2000s, as the China-Africa economic and diplomatic relationship took off, US criticism of China’s role in the region was muted. However, during the Obama administration, senior US officials such as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton began to criticize it more directly and to warn African leaders of a “new colonialism.”8

Such criticism became more acute during the Trump administration, with Secretaries of State Rex Tillerson and Mike Pompeo warning African countries about China’s “predatory” loan practices and that partner authoritarian regimes “breed corruption, dependency and instability, not prosperity, sovereignty and progress.”9

Starting in the late stage of the Trump administration, the United States has not only criticized China’s role in Africa but also attempted to implement alternatives. The Prosper Africa trade and investment policy, proposed in 2018, is one example. The Biden administration’s B3W infrastructure cooperation scheme, meant as a competitive alternative to the BRI, is another example of US-led policies at the heart of the rivalry with China in Africa. Additionally, an intense form of US-China competition in Africa is in the commercial realm, especially in the areas of digital technology and communications.

The United States also continues to be highly wary of China’s growing military presence in the continent, including in port facilities that may adversely impact US military freedom of operations in North Africa and the Horn of Africa. As China’s commercial and citizens’ presence in Africa has grown in recent decades, so too have the role of China’s military and private security firms grown. Such developments have also drawn the attention of the American military’s Africa Command.

In sum, China has based its competitive advantage in Africa on its claims about historic developing-country solidarity with the region, which in turn has been bolstered by a rapid rise in the last two decades in trade, investment, and financial relations.

China continues to prioritize Africa as a key part of the BRI, even as it has moved away in recent years from some of the state-led loans-for-infrastructure deals that existed even before the BRI. While not jettisoning projects in traditional infrastructure like railroads and highways, it now focuses more on technology and energy connectivity. Moreover, Africa is a key site for China’s health diplomacy under the rubric of the Health Silk Road, including via technology cooperation.

The United States has been pushing back against China’s growing influence in Africa for at least a decade, with this reaching a crescendo during the Trump administration. The Biden administration has toned down the criticism while proposing to compete with China in infrastructure, technology, and health governance. Today the United States seems less committed to “extreme competition” against China in Africa than in Southeast Asia or Latin America.

While China’s comprehensive commercial and diplomatic presence in Africa has made it an important actor in the region and the United States has deepened its engagement there, Europe’s position remains strong. This is due to geographic proximity and to strong, historic trade and people-to-people ties to the region. Through its Global Gateway strategy, the EU can build on these factors to develop its commitments to “sustainable and trusted” partnerships there. The Global Gateway’s focus on “digital, climate and energy, transport, health, and education and research” cooperation provides a strong starting point for reinvigorated links to Africa, regardless of how US-China rivalry plays out there.

2.3 Latin America: Rivalry amid booms and busts

As in Africa and Southeast Asia, contemporary competition between China and the United States in Latin America has roots in their Cold War rivalry, although this never matched the intensity of US-Soviet rivalry there.

China’s rise as a major economic and diplomatic player in the region stems from the dramatic take-off in commodity exports from South America beginning around 2003. Within a few years, China became the largest trade partner for a growing number of South American countries, based on its rapidly expanding demand for Chilean copper, Argentine soya beans, Brazilian iron ore, and Venezuelan and Ecuadorean oil.

At the same time, high-level diplomacy increased as Chinese delegations to the region touted rapidly expanding trade ties, promised hundreds of millions of dollars in direct investment, and offered an economic and diplomatic alternative to US and Western leadership, including through the BRICS group of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.10

During these boom years in the China-Latin America relationship, the United States’ response was muted, because of Washington’s focus on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as its appraisal that China’s economic forays in the region could support development opportunities that might quell other risks to the United States, such as illegal immigration and drug trafficking.

The global financial crisis of 2008/09 strengthened China’s role in Latin America due to its continuing strong demand for the region’s commodities.11 However, the end of the global commodity boom in 2013/14 ushered in a new, more difficult phase in the relationship.

Just as China’s growth model, including a rapid increase in demand for minerals like iron ore and copper to fuel the country’s massive property and infrastructure buildup, had fueled the boom, changing patterns of Chinese demand also played a role in the end of the boom. China’s claims that its commodity-based ties with countries like Brazil or Venezuela were stable and conducive to development have been undercut by economic and political crises in these and other countries in the region.

China had argued to its Latin American economic partners that—because it was also a developing country that prioritized South-South engagement—their complementary commodity-based ties were fairer and more stable than the historic patterns of boom-and-bust relations with the United States and Europe.12

Yet, in part because of the commodity-dependent nature of their ties, the China-Latin America relationship has experienced periods of boom and bust. These fluctuations and their associated economic and political volatility have played into Chinese perceptions of Latin America as a region less predictable and riskier than Africa or Southeast Asia.

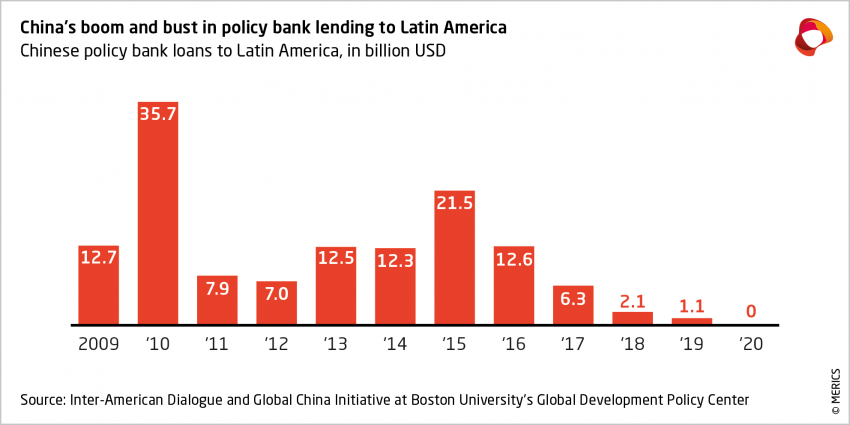

The end of the commodity-boom period overlapped with China’s push to finance and build more infrastructure (in transport, energy, and digital) in the region, including under the BRI. This had the greatest impact in Central America and Caribbean countries, where China signed a large number of memorandums of understanding linked, for example, to port and investment zones.

The expansion of the BRI to these countries was in some cases also associated with a change in their diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC, which raised the ire of the United States. With the creation of the forum between China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in 2010, Beijing sought to replicate similar forums like the FOCAC in the China-Africa relationship.

This period coincided with the Trump administration, which took a much more critical line than its predecessors on China’s economic and political ties to the region, including the extension of the BRI and the establishment of formal diplomatic ties with countries in Central America and the Caribbean, as well as on China’s “predatory” lending in places like Venezuela and Ecuador in South America.

The current US-China rivalry in Latin America builds on these earlier two phases. China’s economic and diplomatic position in the region has transformed from what it was in the commodity-boom “honeymoon” into a more mature and in some ways less state-driven relationship. State-backed lending to the region has decreased while political and economic crises in some of China’s closest regional partners (such as Brazil and Venezuela) have left Chinese officials more sensitive to perceived political risk in the region.

For example, Chinese policy-bank finance, once flowing in the tens of billions of dollars a year, has practically dried up. These trends were already well underway prior to the Covid-19 pandemic due to the sense in China that official financial flows were an inefficient use of public funds and to growing clampdowns on capital outflows. Since the pandemic, even the relative trickle of such finance to Latin America has all but come to a stop as Beijing has prioritized the policy banks’ role in domestic economic recovery and emphasized health and digital cooperation.

In the waning days of the Trump administration, the newly created US Development Finance Corporation (DFC) orchestrated a deal with Ecuador to swap Chinese oil-backed loans for US ones in return for the country keeping Huawei out of its 5G telecommunications network. The Biden administration has toned down US criticism of China’s role in Latin America and the region may increasingly feature as a test case for its B3W scheme. For example, officials have recently traveled to Ecuador and Panama to sound out options for US-backed infrastructure projects in these two countries that in recent years have had increasing cooperation with China on energy (hydroelectric dams) and transport projects (the Panama Canal).13

Commercial competition, including in technology infrastructure (5G and future telecommunications infrastructure) and green-energy resources (like lithium) and electricity transmission, are new arenas of US-China competition in Latin America. While the Trump administration’s deal with Ecuador highlighted the growing tech competition at the government level in the region, access to minerals critical for the transition to greener technologies are likely to involve more private-sector competition.14

Other developments to watch include whether countries like Honduras switch their diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC and if Beijing is able to deepen its links with strategically important countries, like Panama with its transportation infrastructure.

Ultimately, China’s economic and political influence in Latin America will continue to be only as strong as its commodity-based links to the region. Official Chinese lenders and investors will continue to perceive much of the region as presenting heightened levels of risk for as long as its countries grapple with the economic, social, and political aftereffects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Yet, given that the United States has frequently been a fickle partner for these countries, their government and business leaders will continue to look for alternatives. The US and Chinese governments and firms will certainly heighten their competition in Latin America in the key arenas of technology (especially green tech) and energy infrastructure in the years ahead, but the region’s needs in these will continue to be great.

This environment will continue to present options for European trade, investment, and diplomacy. Portugal and Spain have strong people-to-people, cultural, and commercial connections to Latin America, while France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom have similar links with the Caribbean. The EU has been engaged in long-term negotiations over a major free-trade agreement with Mercosur (the Southern Common Market).

Depending on the outcomes of this year’s presidential election in Brazil, a breakthrough in completing it could be possible. Latin America will face an uphill battle in its economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, not to mention the longer-term challenges of shoring up health care systems for future challenges or crises. Amid the ongoing US-China rivalry there, the EU can build on its longstanding ties to the region while using its Global Gateway strategy to create new forms of connectivity.

3. The EU is well positioned to provide attractive alternatives in times of heightened US-China competition

If heightened US-China competition in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia is a key feature of the new era of heightened great-power rivalry, there are important implications for the EU. In short:

- In Southeast Asia, the EU needs to establish for itself a central role in providing alternatives to China in the economic, technology, connectivity, and governance spheres.

- In Africa, the EU should leverage its proximity and existing economic and societal links to build genuine partnerships.

- In Latin America, the EU should build on its long-standing as well as more recent economic and cultural ties to provide sustainable, long-term cooperation as the region rebuilds after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Southeast Asia stands out because of its broad importance to European prosperity and interests as well as the risks there. The EU and its member states, as well as the United Kingdom, have recognized the importance of the region in their respective Indo-Pacific policy documents. Almost all see the risks, especially for maritime security, of the growing US-China strategic rivalry spilling into armed conflict over Taiwan or elsewhere in the South China Sea.

The new European focus on the Indo-Pacific also involves a concern about the existing or potential destabilizing impacts of growing US-China tensions in Southeast Asia. Therefore, one European priority in the Indo-Pacific is to play a constructive role in ensuring that Southeast Asia remains stable and prosperous. European Indo-Pacific strategies also emphasize the need to understand beyond the security arena the importance of the region and the intensified US-China rivalry there. Just as China and the United States have come to see the region as a priority for their economic security and prosperity, so does Europe.

This economic focus includes concerns about supply-chain resilience or any US-China decoupling. But the emphasis is also on opportunities for increased trade and investment in Southeast Asia, including building on EU trade agreements such as the one with Vietnam. European governments and firms are thus part of the competition in the broad economic arena in the region, including in technology and services.

In this regard, Europe’s focus on the Indo-Pacific has emphasized the importance of green technology and standards setting as an advantage relative to the United States and China. Therefore, just as the US-China rivalry in Southeast Asia is comprehensive, so too are its implications for Europe’s role in the region.

Proximity and historic and people-to-people links make Africa the region of most immediate relevance for European policymakers and businesses. As the November 2021 FOCAC again highlighted, China’s development-focused diplomacy continues to focus on Africa. The Biden administration, meanwhile, is attempting to downplay explicit rivalry with China in Africa and highlighting how competitive and trustworthy the United States is as a partner for countries in the region.

Yet, US support for the B3W in Africa, for example, is highly dependent on stimulating new private capital commitments while the region is less of a priority for Washington than the Indo-Pacific. For Europe, China’s economic and diplomatic presence in Africa will continue to draw attention because of its importance for the region but also due to ongoing controversies surrounding it.

Health governance related to the Covid-19 pandemic, especially concerning access to vaccines, will continue to be a focus in EU-Africa relations. At the same time, China and the United States are likely to continue to intensify their competition over technology and digital standards. As the EU pursues its Africa-EU Partnership, and as France continues to try to build on its recent Africa-France Summit, Europe’s role as a partner in African innovation will put it in direct competition with similar Chinese and possibly US initiatives.

Europe also has an important role to play in Latin America and the Caribbean against the backdrop of US-China rivalry. It is a key region for the EU’s efforts to expand its role as a rule-setter and standard-setter in trade, technology, and green energy, all of which are included in the negotiations over the EU-Mercosur free-trade agreement.

A matter of particular importance for the EU will be China’s evolving presence in Latin American energy. This will include Chinese firms’ growing role in South America’s energy transmission grids and in the competition for minerals important for renewable-energy technologies. US firms will also continue to be active in these arenas as well as in other ones of connectivity as Washington seeks to partner with Latin American governments on renewable-energy infrastructure, potentially heightening competition with Chinese and European firms.

One area of potential overlap in US and European interests in Latin America is in sharing with its countries lessons about investment screening based on the US and EU experience in recent years.

Among EU countries, Spain has especially deep economic, diplomatic, and people-to-people links to the region and has an important role to play in the evolving EU ties to it. Over the last two decades, Spanish banks, energy firms, and telecommunications companies have paid keen attention to China’s growing role in the region, but also to rising US-China tensions there.

Last, Venezuela continues to be of importance and interest for Europe, the United States, and China alike due to the country’s multipronged economic, political and humanitarian crisis. An effective response to Venezuela’s long-term, destabilizing, and climate-unfriendly dependence on its oil reserves might present the opportunity for a European-led recovery plan in the years ahead.

Given its upgraded tools such as its Global Gateway and Indo-Pacific strategies as well as the policies presented in the recent EU-Africa Summit, the EU is well positioned to provide attractive alternatives in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Yet, for those alternatives to be attractive and for those strategies to live up to their potential, including in key areas such as green energy and technology, a coordinated diplomatic presence as well as the provision of concrete projects and measures of progress are required.

The broad US-China strategic rivalry, including their more focused competition in these regions, will intensify in the years ahead. This will underscore the role and relevance of Europe as an attractive partner for economic opportunity and diplomacy. The EU will not be able to remain on the fence as the US-China rivalry in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia intensifies. By following through on its new tools and strategies, as well as its interests and values, it will be well positioned in an increasingly competitive environment.

- Endnotes

-

1 | Matt Ferchen (10 February 2021), “Towards ‘extreme competition’: Mapping the contours of US-China relations under the Biden administration,” https://merics.org/en/report/towards-extreme-competition-mapping-contours-us-china-relations-under-biden-administration.

2 | Matt Ferchen (2 November 2020), “The competition over competitiveness: US-China relations and the US presidential elections,” MERICS, https://merics.org/en/opinion/competition-over-competitiveness-us-china-relations-and-us-presidential-elections.

3 | See Joshua Kurlantzick (2008), Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World, Yale University Press.

4 | See Evelyn Goh and Nan Liu (2021), “Chinese Investment in Southeast Asia, 2005-2019: Patterns and Significance,” Australian National University Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, https://www.newmandala.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/GohLiu_-SEARBO2_Chinese-Investment-in-Southeast-Asia-2005-20192.pdf.

5 | See David Shambaugh (2020), Where Great Powers Meet: America and China in Southeast Asia, Oxford University Press.

6 | Laura Rosenberger (11 January 2022), “Navigating Tumultuous Times in the Indo-Pacific,” National Bureau of Asian Research, https://www.nbr.org/event/navigating-tumultuous-times-in-the-indo-pacific/.

7 | Ben Kesling and Jon Emont (9 April 2019), “U.S. Goes on the Offensive Against China’s Empire-Building Funding Plan,” The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-goes-on-the-offensive-against-chinas-empire-building-megaplan-11554809402.

8 | “Clinton warns against “new colonialism” in Africa” (11 June 2011), Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-clinton-africa-idUSTRE75A0RI20110611.

9 | Michael Pompeo (19 February 2020), “Liberating Africa’s Entrepreneurs,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, https://2017-2021.state.gov/liberating-africas-entrepreneurs/index.html.

10 | South Africa joined the group in 2010, almost a decade after Goldman Sachs originally touted the acronym for marketing purposes in 2001.

11 | For a detailed study of Latin America’s commodity dependence on China just prior to the end of the boom, see Alicia García-Herrero, Matt Ferchen, and Mario Nigrinis (2013), “Evaluating Latin America’s Commodity Dependence on China,” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2253159.

12 | For more on contested portrayals of the China-Latin America trade relationship as based in “complementarity” or “dependency”, see Matt Ferchen (2011), “China–Latin America Relations: Long-term Boon or Short-term Boom?” The Chinese Journal of International Politics, https://academic.oup.com/cjip/article-abstract/4/1/55/325615.

13 | See Patsy Widakuswara (24 November 2021), “‘Build Back Better World’: Biden’s Counter to China’s Belt and Road,” https://www.voanews.com/a/build-back-better-world-biden-s-counter-to-china-s-belt-and-road/6299568.html.

14 | For an overview of the wide range of China’s energy-based involvement in Latin America, see “China Stakes Its Claim in Latin American Energy: What It Means for the Region, the U.S. and Beijing” (2021), Institute of the Americas, https://iamericas.org/china-stakes-claim-latin-american-energy/.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Ford Foundation grant and is licensed to the public subject to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Media Contact

The experts of the Mercator Institute for China Studies are available to comment on current news, as panelists or as op-ed authors.