De-risking viewed from China + EU anti-coercion instrument

Analysis

“EU-China spring” challenges EU’s strategic communication on de-risking

By Grzegorz Stec

“Spring for China-Europe cooperation has arrived,” was the announcement made by Beijing after French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen touched down in Beijing. Several Chinese intellectuals echoed this, labelling a lineup of European leaders’ visits to China a “little spring thaw” (小阳春).

The reengagement proceeds despite several unresolved points of tension between the EU and China, such as Beijing’s continued support for Moscow, differing visions of the international order going forward or human rights abuses in Xinjiang, to name but a few.

This may appear to be a contradiction, making the EU’s strategic communication on China and towards China increasingly complex. In an era of emerging bloc politics and battles of narratives, such lack of clarity amounts to a strategic vulnerability, that is, the EU’s position can easily be misinterpreted on purpose to limit the desired impact.

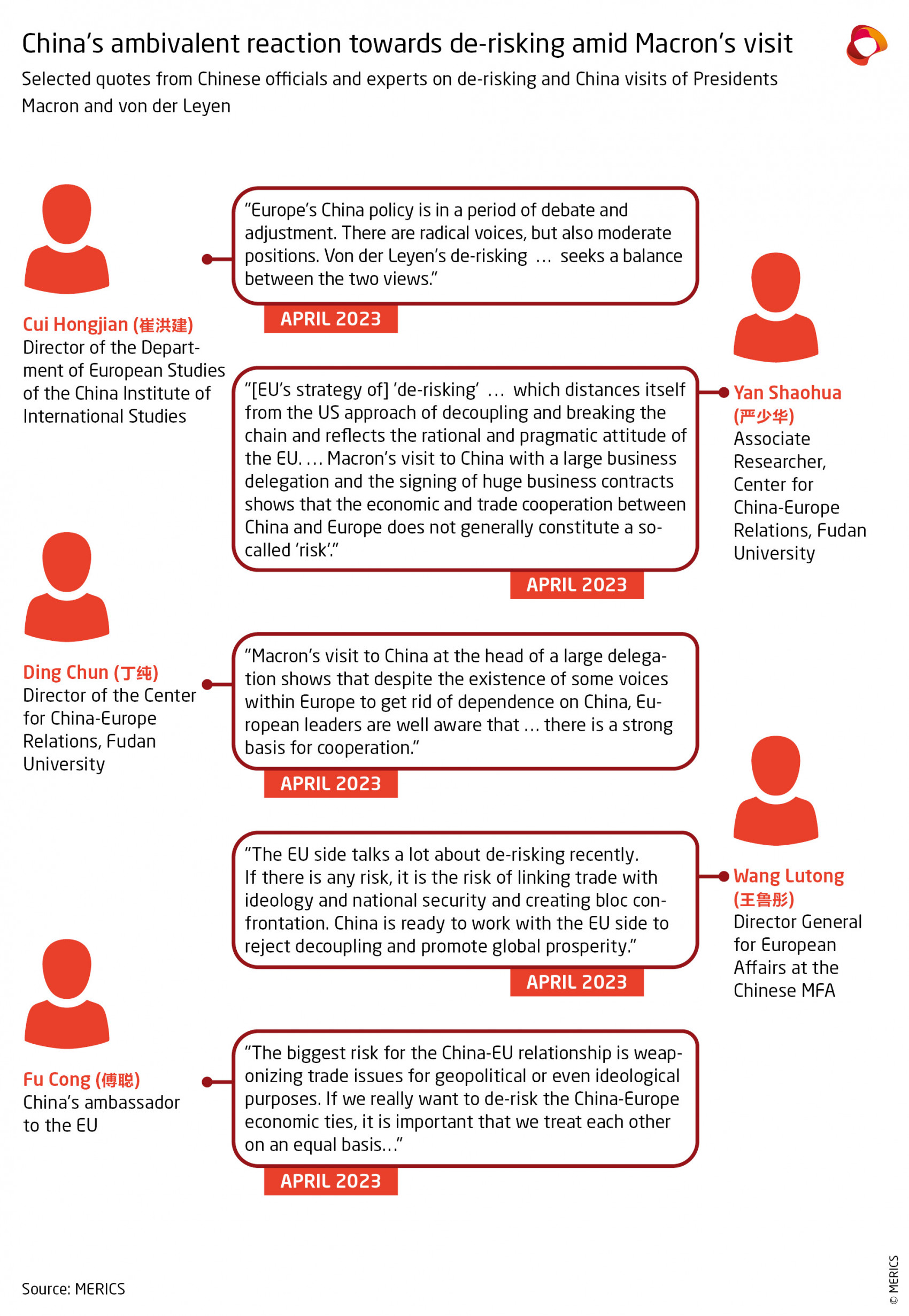

Discussions of Chinese officials and think tank experts surrounding von der Leyen and Macron’s China visits show the potential for the EU to pursue its engagement with China under the frame of de-risking, but also highlight the urgent need for the EU to convey a coordinated and consistent message.

De-risking viewed from China: glass half empty, glass half full

Ahead of her trip to Beijing alongside Macron, President von der Leyen tried to frame the re-engagement as one part of the EU’s wider – and increasingly assertive – China policy. In her most comprehensive speech on the EU’s China policy to date, von der Leyen argued that the EU needs to “de-risk, not decouple” in its relations with China through political and economic de-risking (see our latest MERICS China Essentials for speech details). Her trip to Beijing was to an extent a communication mission to speak frankly with Chinese counterparts, at the same time, leading by example and showing what a de-risking form of engagement looks like for other European leaders to emulate going forward.

Despite initial knee-jerk reactions from Chinese diplomats, Chinese experts did not dismiss the “de-risking” agenda, pointing to some positive implications for China in von der Leyen’s overall assertive policy proposal.

For instance, Cui Hongjian (Quote 1) stated that the approach is an attempt by the Commission to find a space between the “two extremes” in European discussions on China policy. Yan Shaohua (Quote 2) and Peng Chongzhou from Fudan University Center for China Relations also pointed out that the de-risking rhetoric means that while the EU shares the US assessment of the challenge posed by China, it develops a different policy response – and such differences between the transatlantic partners are welcomed in China’s books.

Several Chinese analysts also emphasized that the approach explicitly leaves room for cooperation with China in areas that do not fall under the “risky” category. The engagement-focused visit of President Macron and his 50-strong business entourage facilitated a flurry of business deals, ranging from sales deals of Airbus aircraft to Alstom’s metro construction contracts. It was interpreted as proof that the European leaders remain committed to doing business despite the EU’s emphasis on risk-mitigation measures. Opinions differed as to whether this contradicts the de-risking logic or whether this type of engagement can be considered “un-risky.”

China will create its own interpretation of “de-risking”

But as the EU debates embracing the de-risking frame for its China policy, it should be mindful of Beijing’s potential attempts to hijack or redefine the meaning of the concept. In the immediate aftermath of President von der Leyen’s speech, Chinese MFA officials (Quotes 4 and 5) pushed to reframe the concept to mean preventing a spillover of ideological differences to economic relations and opposing geopolitical bloc building – both interpretations aligned with Beijing’s objectives.

Such redefining is not new in China’s communication strategies. Beijing’s routine attempts to reduce the EU’s concept of strategic autonomy to simply mean decreasing the EU’s reliance on the United States, is but one example.

A lack of clarity around this concept was present also during the visit. In her engagement with the press, von der Leyen spoke of the EU’s “open strategic autonomy” as a primarily defensive and policy-focused response, highlighting, for instance, coordinated pandemic responses or the mitigation of vulnerabilities stemming from potential supply chain breakdowns. In turn, President Macron sent signals in favor of “strategic autonomy” understood primarily as expanding the EU’s autonomic capabilities and pursuing the “third way” approach as an alternative to bloc-building created by Sino-American rivalry.

Macron referenced de-risking as a tool for achieving that goal by limiting dependence on other actors, primarily in reference to the US. Macron also controversially suggested that the EU should avoid being dragged into escalations surrounding Taiwan in a way that would undermine its strategic autonomy efforts, a statement that has been critically received in many European capitals.

Inconsistencies in strategic communication weaken the EU’s position

These kinds of inconsistencies in strategic communication on key concepts from EU leaders weaken the EU’s geopolitical position.

The visit of Macron and von der Leyen to China was a major opportunity for the EU to set the tone for the EU’s ongoing diplomatic reopening and to project a distinct European position that is clear-eyed about the differences between the EU and China. However, the insufficiently coordinated messaging leaves the EU exposed to China – and arguably also other actors – to hijack the EU’s narratives for their own ends.

With German Foreign Affairs Minister Annalena Baerbock already in China, subsequent upcoming visits from European leaders, and discussions on the de-risking agenda likely to take place between EU capitals before the EU-China summit expected in a few months, developing a coherent strategic communication strategy on engaging with China should be the priority for the EU. Von der Leyen’s suggestion appears to be a sober middle ground position for the EU to explore. While Brussels’ hope for EU members to sing from the same hymn sheet may remain out of reach, they should still develop a unified melody to which they can all sing along.

Read more:

- Cui Hongjiang on President von der Leyen’s de-risking concept [CN]

- Yan Shaohua on de-risking and President Macron’s visit [CN]

- Ding Chun on President Macron’s visit [CN]

- Tweet by Wang Lutong on the concept of de-risking

- Ambassador Fu Cong: Why China-EU relationship matters

- Sinification: The Importance of France and Macron to China

RECOMMENDED READING

Six priorities for “de-risking” EU relations with China

Brussels and European capitals are discussing the idea of “de-risking” relations with China – essentially, limiting the EU’s vulnerability to a wider range of stress factors and possible disruptions caused by Beijing as well as China-related geopolitical tensions. A comprehensive, long-term de-risking will only succeed if it builds on:

- the responsible management of strategic divergence of the EU’s interests and values with China

- the effective implementation and expansion of the EU’s defensive policy toolbox

- a coordinated but independent European approach to high-tech relations with China

- a proactive reduction of strategic vulnerabilities, especially in critical raw materials

- much higher preparedness for a Taiwan conflict

- the right dose of China policy coordination with transatlantic and like-minded partners

Read the full opinion piece in the IP Quarterly by MERICS Executive Director Mikko Huotari and MERICS Analyst Grzegorz Stec here.

Update

Habemus anti-coercion instrument

On March 28, European institutions reached a political agreement on the anti-coercion instrument (ACI), which seeks to frame and delineate how the EU should respond to third countries “…restricting or threatening to restrict trade or investment to bring about a change of policy in the EU…”

What you need to know:

- What is the ACI for and why does the EU need it? Although the European policy response was born out of concerns linked to the Trump administration, it eventually developed around worries of China’s leverage of economic linkages to either punish foreign countries or compel policy/behavioral change from them. In the EU, Lithuania’s case of an informal restriction being placed upon imports from China or exports of products with Lithuanian components to China, as an informal response by China to the country for its decision to open a Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius, is notable. Non-European examples of China adopting economic coercive practices include Australia, Japan and South Korea, to mention a few.

- What are the salient points of the ACI? Initially, the European Commission can trigger the process to establish the existence of economic coercion following “substantive” requests. It is the Council, however, that decides whether it is a case of economic coercion, and if the response is yes, then the next phase can be initiated. In this phase the onus is back on the Commission to consult with the country enacting economic coercive measures to solve the issue diplomatically. If that fails, then the European Commission can propose countermeasures, which are to be adopted by the Council. The Parliament is to be consulted both to determine whether there is an instance of economic coercion and to adopt the appropriate measures.

- The countermeasures. The list of possible countermeasures was a delicate point during negotiations between the Commission, the Council, and the Parliament. Ultimately, the list includes interesting measures such as the possibility to adopt export controls, the suspension of IP rights, denying access to the EU’s public procurement market, and possibly an ability to restrict research cooperation.

What to watch:

The ACI may well signal a watershed moment for the EU, in particular for the Commission’s role in implementing economic security policies. Prior policies, such as the investments screening mechanism, lay at the intersection between the remit of the Commission, trade and investments, and that of member states, foreign policy and security. Although with ACI a lot remains in the hands of the Council and thus of member states, whereas the Commission covers a central role of consulting with the country deemed to have adopted coercive economic behaviors and then, if necessary, adopt countermeasures. With the forthcoming Commission’s launch of an economic security strategy, it may lead to an enhanced role for the European Commission in economic security matters and thus, hopefully, a much-needed coherent and united response from the EU. At the same time, the ability of the Council to judge whether economic coercion is occurring still offers an opening for China’s direct or indirect pressure, as well as an opportunity to magnify any European divisions should an agreement not be reached quickly.

Read more:

Short takes

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez in Beijing

Largely overshadowed by the visit of French President Macron, the visit of Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez also had a somewhat controversial agenda. The first stop on Sanchez’s visit was not a meeting with Xi Jinping in Beijing but an appearance at the Boao Forum, China's answer to Davos. Furthermore, Sanchez, much like Macron, carried an agenda that suggested, rather than a de-risking, a deepening of economic relations.

- Reuters: Spain PM urges Asia to open market to Western companies

- Global Times: Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez's visit to China is a win-win game

NATO Secretary-General warns China on providing weapons to Russia

In an April 3 pre-ministerial press conference, Stoltenberg warned China that providing weapons to Russia would be “a major mistake”. The statement is in line with NATO’s direct concerns regarding the war in Ukraine and the alliance’s increasing attention to China. Recently, NATO has also banned Tik-Tok from NATO devices.

Intelligence in Belgium places Huawei on watchlist

The Belgian intelligence services are worried that Huawei’s office in Brussels may be conducting espionage activities targeting European institutions and NATO. The main concern is that the Chinese company may be using its lobbying activities to further the interests of China in the European capital.

Volkswagen will set up electric vehicle academy on Hainan

The academy intends to train local talent in a sector where such talent is lacking. Launched in Anhui, this is the second such facility coming out of a decade-long program. It will further deepen Volkswagen’s exposure in the Chinese EV market and empower Chinese talent in what used to be a European dominated sector. Other large companies operating in the EV sector are also strengthening their commitment to the Chinese market, such as Tesla, who will build a factory to produce megapack batteries in Shanghai by the second quarter of 2024.

- South China Morning Post: Volkswagen aims to fill China’s electric car industry talent void with new academy in Hainan

- Wall Street Journal: Tesla to Build New Megapack Battery Factory in China

Italy’s governing party cancels delegation trip to Taiwan

For the second time, a delegation from Brothers of Italy, the leading party in the governing coalition, has postponed its trip citing “international tensions” as the main reason. The leader, and current Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni was seen as a supporter of Taiwan during the elections in September, but since becoming PM, has yet to clarify Italy’s position towards China.