Reconnecting in a digital world: How Chinese youth navigate the decline of local communities

Summary:

- The search of Chinese netizens for lively shared experiences and human interactions speaks to a growing trend: as digital infrastructure and e-commerce grow, physical places have become less significant, making tangible, sensory experiences a rare pleasure for city dwellers.

- The two examined online groups both seek online solutions for “over-digitalization,” but with different approaches. One group focuses on fostering offline connections, while the other group uses digital tech to meet social needs.

- This analysis challenges the common perception of China as solely an advanced digital society driven by top-down tech development and tech enthusiasts longing for comfort. It reveals that Chinese people experience similar struggles due to over-digitalization, much like individuals worldwide.

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

Returning to life offline: the search for yanhuoqi

Announced as one of China's internet words of the year in 2023, yanhuoqi (烟火气) is a phrase that roughly translates to the sensory experience of smoke and fire. It evokes the lively atmosphere of communal eating, something for which China's online community expresses a longing. The search for a communal lifestyle, particularly in bustling streets with food stalls gained prominence in May 2023 when 4.8 million tourists suddenly flocked to Zibo in northern China to enjoy local grilled skewers. Similar patterns continued into 2024, with vibrant night markets in Changsha, morning markets in Harbin, and small community-focused Malatang soup shops in western China’s Tianshui becoming popular destinations.

The longing for yanhuoqi is symbolic of a wider trend: the desire to reconnect with tangible, sensory experiences and human interactions in a world where relationships and exchanges are frequently mediated by screens, algorithms, and digital platforms.

With phones now indispensable, power bank rental stations have become a ubiquitous and unique part of the streetscape in Chinese cities. The rapid expansion of digital infrastructure has made local physical spaces less significant for China’s urban middle class. Thanks to efficient “last-mile solutions,” tech companies have become more and more capable of seamlessly delivering goods onto customers' doorsteps, no matter where they live.

Transactions have become more impersonal: everyone knows exactly when the food will be delivered to their door, but not from where or by whom. The pandemic further accelerated the adoption of delivery services and remote interactions. Since then, a place with yanhuoqi has become a rare pleasure for city dwellers.

In a 2019 Chinese talk show, Chinese sociologist Xiang Biao (项飙), director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Germany, discussed the erosion of public life in Chinese cities, a topic that quickly went viral in China and resonated deeply with many viewers. His observations are still widely quoted in discussions about over-digitalization, as they capture a major societal trend that continues to unfold.

According to Xiang, young urban residents lovingly furnish their apartments with large TVs and smart home devices. On social media they actively engage in a global discourse on topics like geopolitics. Yet, while they are well-connected virtually, they often overlook their immediate surroundings. Xiang concluded that “the nearby is gone,” and in response, he advocates for the “first 500-meter movement,” emphasizing the importance of re-engaging with the first 500 meters from our front doors to counter the disappearance of local-community engagement and the weakening of social cohesion.

Douban groups: exploring digitalization and loneliness in online discussions

To understand how netizens in China are coping with an omnipresent digitalization, we identified and analyzed two online communities on the Chinese social media networking site Douban.1 The “Anti-technology dependency” group (反技术依赖小组) questions existing technological structures by exchanging ideas and examples for new, less technology-dependent behaviors. In contrast, members of the group “The 50 challenges of living alone” (独居的50个挑战) use digital technologies to reproduce social structures online to meet their social needs that are difficult to fulfill when living alone.

The digital detoxers

The “Anti-technology dependency” group claims that technology increasingly acts as a form of social control, turning individuals into “servants of things,” meaning they become overly reliant on gadgets and digital devices, often without realizing it.

They hope to collectively learn skills such as how to maintain offline social relationships and develop specific survival skills useful if technology ever were to fail.

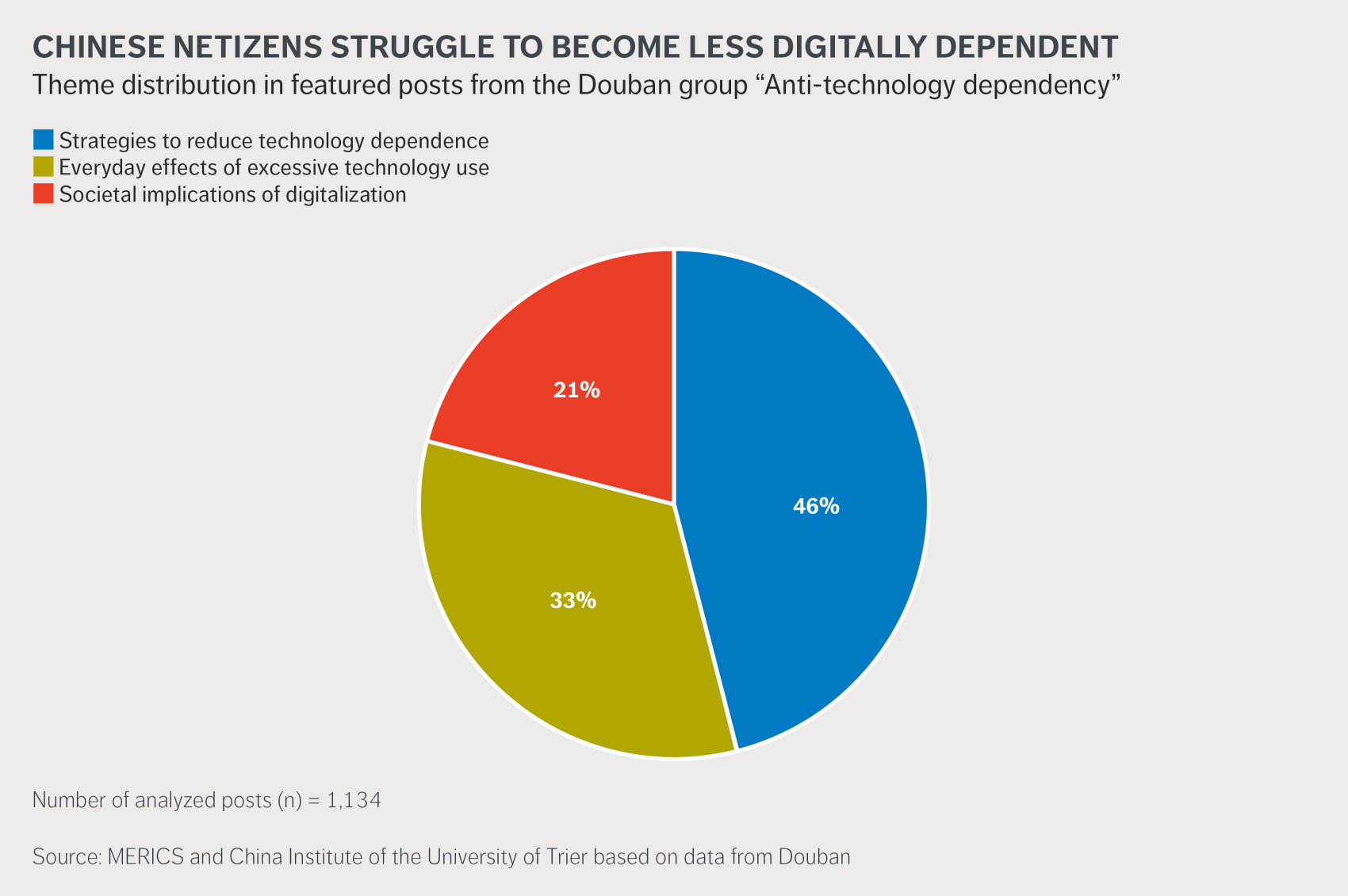

A central theme in the group, making up 33 percent of the discussions, is the daily impact of excessive technology use. In her thread, user wef355 describes her daily experiences and concerns: “People used to ask for directions when they were lost; now if you ask someone for help, they might question your intentions and say, 'Don’t you have a navigation app?’” Similarly, she writes, “in many restaurants there are no menus anymore; you scan the QR code on the table, which leads to an ordering page. This system is like ordering food through delivery apps and removes the human warmth.”

Members of the group exchange various strategies to reduce their technology dependency, making up 46 percent of the total posts. The user Shadan shared his experiments. He avoided smartphones, preferring a basic phone, an MP3 player and film camera. At university, he experimented with not bringing a phone to class, increasing his engagement and focus.

Critical reflections of society make up 21 percent of the discussions in the group. In a thread the user Xiaoshidedipingxian describes the superficiality and time-wasting associated with using short video apps: “You swipe your finger across the screen and feel like a judge of the world, arrogant and superficial. You chase trends, unleash emotions, and gather useless knowledge. Despite the considerable time invested, little of value remains.”

Users also explore the intersection of consumerism and digitalization. Maoshiwusuoharu expresses her thoughts: “Today, every app wants to do everything for us, suggesting that life only works through constant connectivity. But it’s all about money: the more and faster we consume, the more providers earn. In the end, technology consumes us, like in the classic Nokia game of Snake: it grows so large that it devours itself.”

Refuge, comfort and digital connections

The Douban group “The 50 challenges of living alone” fosters a culture of anonymous yet intense exchange by prohibiting the sharing of selfies and contact details.

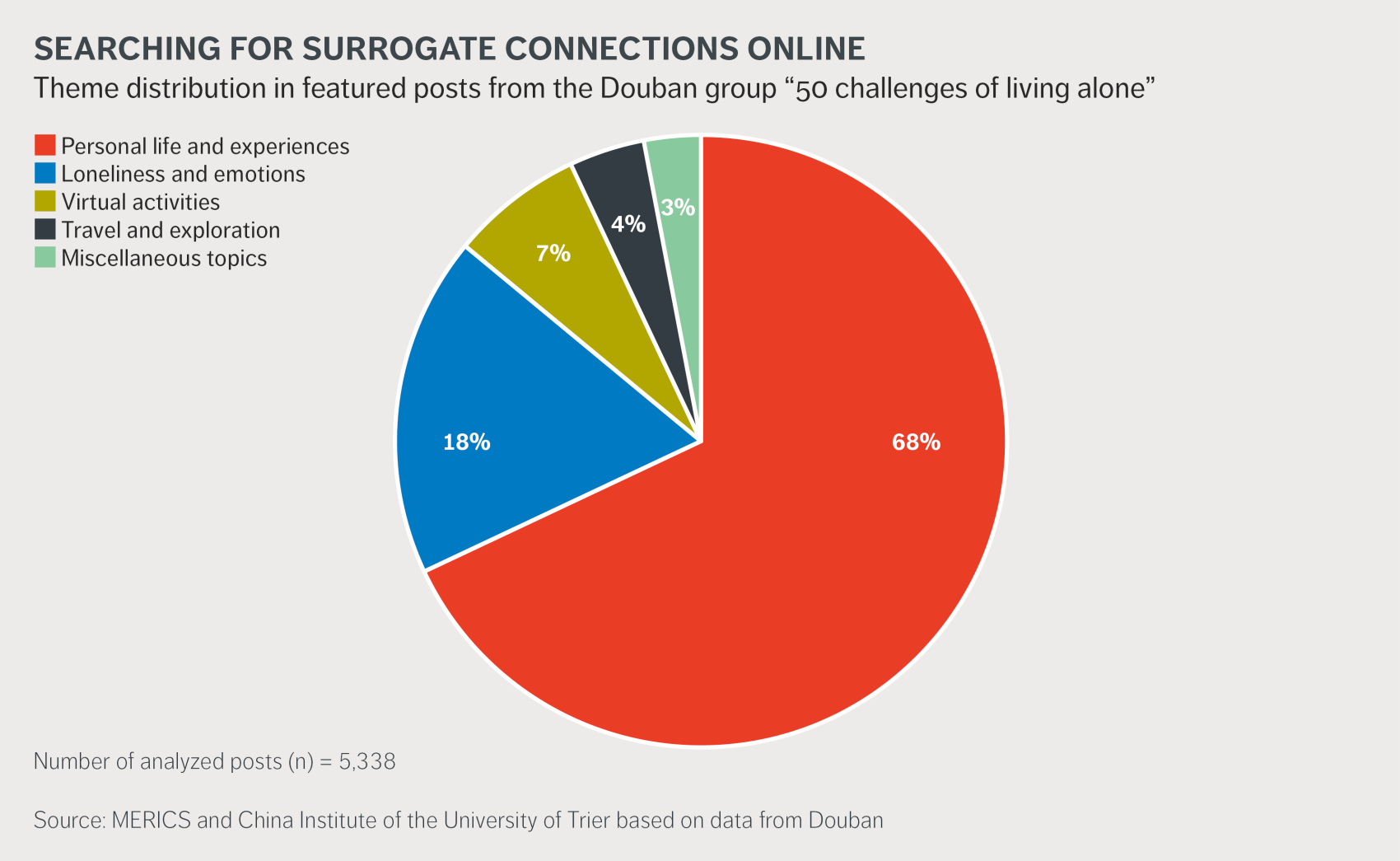

Posts about loneliness make up 18 percent of the threads. This is not surprising, as the number of single households in China has been increasing, according to official statistics. In 2000, 2.52 percent of Chinese households had a single occupant, in 2022, this percentage stood at 16.8 percent. Especially unmarried women often find refuge online.

In one post, a member named Counting Sheep described the emptiness felt after attending a fantastic music performance: “Returning home, I felt a wave of loneliness, as there was no one to share the interesting experience with.” Another user responded by encouraging a shift in perspective, noting, “think about it differently […] you are sharing it right now with us.”

Not all experiences of being alone are negative. In four percent of the posts, group members eagerly share their good moments such as travel or savoring delicious food. Member Maybe shared pictures of her solo Chinese New Year dinner, commenting, “find a good movie, make some delicious food, how cozy! No need to face relatives or put on a smiling face, just nestle into your little corner and happily celebrate.” Artisan asked how she managed to avoid going home, to which another member replied, “first, don’t rely on family, then give them up, and finally live freely alone.”

Practical tips for daily life and discussions about lifestyles dominate 68 percent of the conversations, with a focus on safety and health. Threads such as “some safety tips for those living alone” and “don’t be afraid of getting sick even if you’re alone” provide valuable advice.

In the thread “living alone in a retirement home,” user Heart like shining stars shared her decision to leave the city in her early thirties and move into a retirement home as part-time staff. Unmarried and childless, she anticipates a peaceful future working part-time among the elderly. Her life planning has inspired other members to seek concrete advice from her on applying for jobs in retirement homes. For a group whose members seek refuge and surrogate connections online, alternative lifestyles like these offer an opportunity to get offline.

What does this mean? Disenchanted youth pose challenges to the Chinese Communist Party's national objectives

Discussions on these two Douban groups challenge a common perception of China as a solely advanced digital society driven by top-down tech development. The discussions reveal that Chinese people face similar struggles due to over-digitalization as individuals worldwide: balancing the vast potential of digital technology with the longing for authenticity and human intimacy.

Both groups and their coping mechanisms – digital surrogation and digital detox – follow earlier online behavioral trends and discussions among Chinese youth: “lying flat” (tang ping 躺平; inner retreat at home) or “run” (run 润; leaving the country). Those trends have emerged mainly as reactions due to a challenging offline environment: a huge workload for some (9-9-6 system: nine-to-nine six days a week), no job perspectives for others (the latest official adjusted unemployment figure stands at 13 percent).

However, all those online discussions and behavioral trends point to parts of the Chinese youth being disenchanted and seeking their own ways of sense-making. This poses challenges to the Chinese Communist Party on at least two levels: A disengaged youth undermines social cohesion and is not easy to mobilize with party-engineered terms such as “national rejuvenation” or “building a modern socialist country in all respects.

If triggered by a unifying event, like during the “White Paper” protests in November 2022, Chinese young people might also take own ways of re-engagement to the streets demanding a more active part in shaping their own future.

- Endnotes

1 | With over 200 million registered users and 150,000 active groups on topics such as lifestyle, books, and movies, Douban provided an ideal platform for our analysis. Mainly used by educated urban dwellers aged 18 to 35, Douban allows longer posts compared to platforms like Weibo. This extended format enables more nuanced discussions. We filtered the Douban platform for the terms yanhuoqi (烟火气) and two-dimensional world ( 二次元), the latter referring to the subculture of introverted individuals who are more active online immersing themselves in a world of anime, manga, and video games. Douban also has a “users in this group also visit” function to recommend groups based on similar interests, which allowed us to expand the search results using the snowball method. From 32 groups we identified two groups fitting the chosen criteria of more than 10,000 members, active in the last seven days, discussion of coping mechanisms, be publicly accessible. These two groups illustrate contrasting coping mechanisms in response to the erosion of offline and public life. We then did a content analysis of all “featured” (精选) posts of those two groups.