Losing ground in space

In the space realm, Europe still seeks cooperation with China despite having framed it a systemic rival. This creates serious strategic and economic risks, because Europe is too fragmented to keep up with China’s concerted commercial and military efforts to challenge the US dominance in space.

This article is part 1 of a mini-series to present the outcomes of the MERICS European China Talent Program 2019.

Fifty years after Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the lunar surface, China provided humanity with the first picture of the far side of the moon, captured during the Chang'e 4 mission in January 2019. This event is exemplary for the great advances China has made in space: Within a relatively short time, China has emerged as a major space power that is about to overtake Europe.

Outer space has become indispensable for our current and future society. Whether getting cash from ATMs, checking the weather forecast or making phone calls, all these everyday activities rely on space infrastructure. Satellite navigation alone contributes to about ten percent of Europe’s GDP. It also lays the foundations for upcoming emerging technologies: the Internet of Things, 5G and 6G mobile telecommunications standards and quantum technology will all rely heavily on satellite networks. Longterm, our economic prospects may depend on mining resources from asteroids or space-based solar power.

Unlike Europe, China aims for military expansion

China is turning into a global powerhouse in space matters. Beijing declared the development of its space sector a national priority, with the intention of becoming the world’s leading space power by 2045. It is well on track. In 2018, it had more orbital space launches than any other country. In the year to come, Beijing aims to send a probe to Mars and make its navigation system Beidou (China's answer to GPS) fully operational. A Chinese space station called “Heavenly Palace” is under construction and set to ascend in 2022, potentially replacing the International Space Station (ISS), which is planned to be retired 2024.

Many of China’s space efforts are part of a strategic and military race with the US. Back in 2015, the Chinese army set up a Strategic Support Force to intensify efforts to challenge the US space military. Since 2007, China has had the technology to shoot satellites out of earth’s lower orbits with ground-based weapons and perhaps attack higher stationed satellites with its own satellites. It has made similar advances in developing non-physical space weapons, such as signal interference and cyber-attacks. It even has the technology ready to field a nuclear-armed anti-satellite weapon.

Unlevel playing field vis-à-vis Chinese companies may extend to space

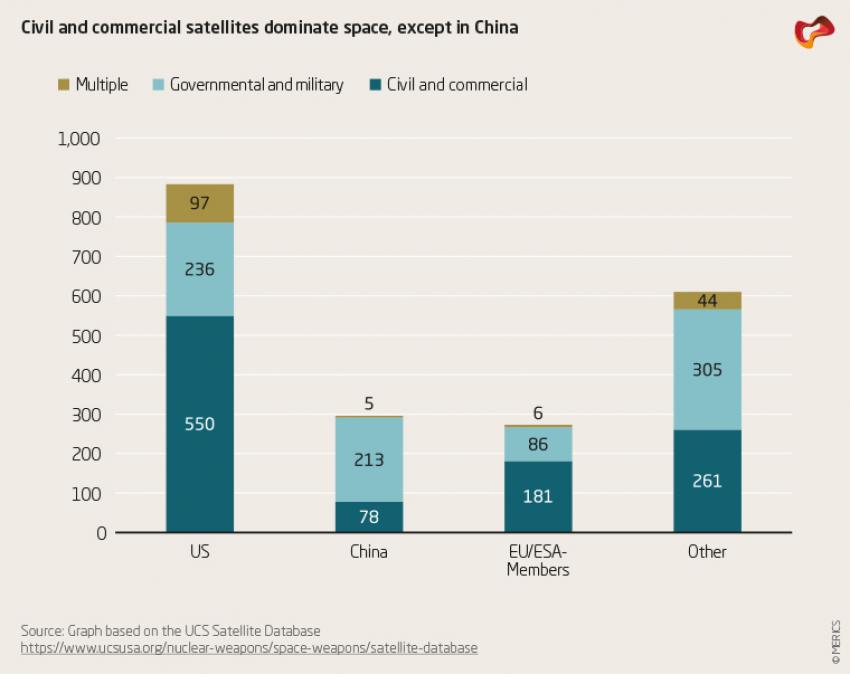

In a trend known as “New Space" private space enterprises are proliferating everywhere. Two thirds of US satellites today serve civil or commercial applications. In the EU, too, civil and commercial satellites dominate. In contrast, of four Chinese satellites, only one is used for civil and commercial use; the other three satellites are deployed for governmental and military applications.

This is, in part, because China is a latecomer to New Space, but also because it is attempting to integrate the emerging commercial industry into its defense industrial base. The People's Liberation Army opened its Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center for private launches and is increasing partnerships with the private sector and leading research universities. By transferring private sector innovation into the defense sector, China clearly hopes to create leapfrog development.

This interaction of private and military sectors should not only raise concerns for Western companies because of dual use technology, it will also make competition in this emerging market increasingly difficult. The "unlevel playing field" vis-à-vis Chinese companies, with which other industries have already been confronted, could soon extend to space.

The curse of fragmentation

To date, Europe has been a major player in the space domain. Traditionally, EU member countries have had full authority in space matters. In some areas they collaborate within the intergovernmental ESA, a non-EU body, but by and large European countries are hesitant to shift from their national space programs towards a joint strategy. To complicate matters further, Britain, one of Europe’s most present space nations, is leaving the EU. Its fragmentation leaves Europe vulnerable to growing dependency and stagnating innovation.

Brushing away the unfavorable Beidou cooperation, Europe is maintaining a collaborative stance towards China and still sounds very positive about future cooperation prospects. Embracing this opportunity, China has established an overseas satellite ground station in Sweden, signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Luxembourg, and now hopes to export its Beidou navigational standard to Europe.

In an increasingly complex and militarized space sector, cooperation with other countries always entails a risk. Europe must avoid losing agency over sensitive space infrastructure and should be aware of becoming too dependent on foreign space technology, especially from systemic rivals. To prevent such scenarios, Europeans should acknowledge the strategic significance of the space domain, rather than treating it as a user-driven market. This would pave the way for long-term investment, something the sector has for a long time called for. When it comes to outer space, joint efforts are the only option for Europe to ensure its lasting independence.

The authors participated in the fifth annual MERICS European China Talent Program in May 2019, during which parts of the argumentation presented in this blogpost were developed. The authors bear sole responsibility for the content.