Germany's recent China policy

Critical human rights debates in the Bundestag, pragmatic economic policy in the Chancellery

By Ariane Reimers (text) and Vincent Brussee (data)

It is still not certain which political parties will govern Germany for the next four years – and the next government’s China policy is even more unclear. Although the left-leaning Social Democrats and Greens and the liberal Free Democrats are now trying to forge a coalition, any eventual stance towards China is hard to discern after an election campaign in which the foreign-policy positions of the seven parties in parliament played little or no role.

For the last 16 years, it was Chancellor Merkel who shaped Germany's relations with China. In her first years as head of government, she pursued a distinctly values-based approach, which, for example, saw her play host to the Dalai Lama in the Chancellery. But with the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 at the latest, she adopted a pragmatic, pro-business course that late 2020 culminated in a deal about the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the EU and China (even if the European Parliament since shelved it).

In retrospect, the Merkel years will stand for a policy that aimed for a partnership with China and to address contentious issues, especially human-rights related ones, by means of "quiet diplomacy." Germany’s reward for this stance was a privileged bilateral relationship.

China's prominence in German political debate has risen sharply since 2017

The key question is whether the next government will continue on this path. The Green Party and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) have been in opposition since 2005 and 2013, respectively, and their attitudes towards China are untested by the pressures of day-to-day government. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) has been in power for the past eight years, but played only a minor role in Merkel’s China policy. To get a more substantive insight into the parties' positions on China, it is worth considering how Germany discussed China in recent years – and, in particular, how Germany’ Bundestag debated issues relating to it.

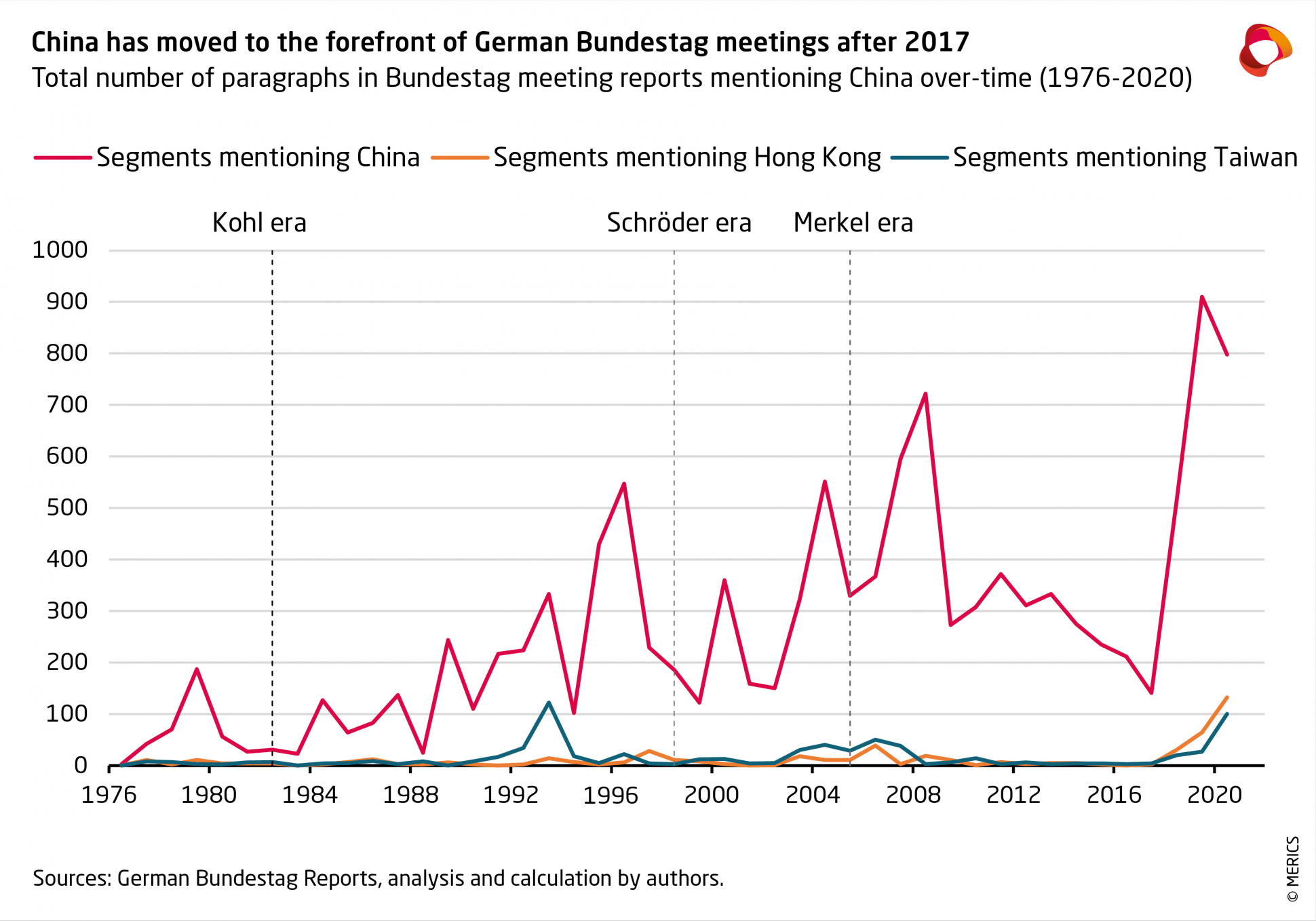

The prominence of China in German politics increased markedly over the last few years (figure 1). In the last legislative period, from late 2017 to late last month, the number of parliamentary debates in which China was mentioned rose sharply. The country was rarely at the center of these exchanges, but was referenced readily as an example of an autocratic system, a counter pole to the US, or an emerging great power with expansionist traits.

Surges in lawmaker interest in China were mostly driven by events there. Regardless of whether it was the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, the Beijing Olympics in 2008, or the National Security Law in Hong Kong in 2020, German parliamentarians usually reacted to China and did not engage in strategic discussions about how Germany might shape a relationship with more foresight. This explains why China receded from the agenda after the 2008 Olympics and only returned to full prominence a decade later, as concern began to mount about human rights violations in Xinjiang and the stifling of freedoms in Hong Kong.

German politicians usually have critical and distanced stances towards Beijing

The tone of members of the Bundestag towards China was critical and usually very different from that of German government ministers. The EU-China sanctions tit-for-tat in early 2021 is a good example. While the government reacted very cautiously to China's counter-sanctions ("we take note"), 281 Bundestag members declared their solidarity with the targeted individuals and institutions: "China's sanctions target the freedom of expression of freely elected members of parliament and are another attack on the freedoms we enjoy."

A closer look at Bundestag debates in recent years shows how distanced and critical many lawmakers were towards China. Merkel’s Christian Democrats largely fell into line with the attitudes of their colleagues from the SPD, FDP and Greens. Members of all parties regularly showed themselves diametrically opposed to Merkel's China policy. Then again, these critical voices in parliament did not have any influence on day-to-day dealings with China – the policy of the Chancellery remained pragmatic and more sympathetic toward Beijing.

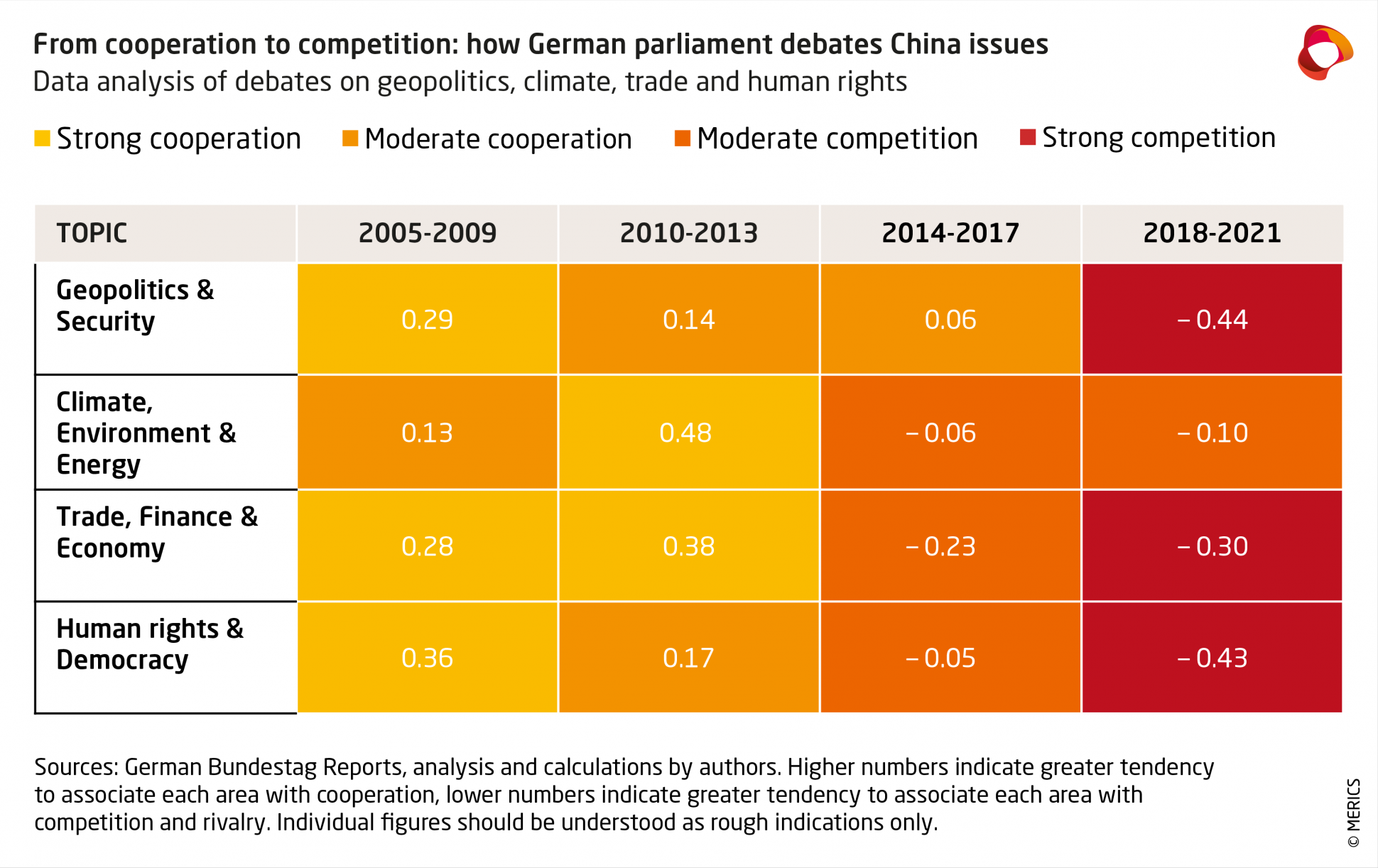

Overall, the Bundestag’s tone toward China became increasingly strident in recent years (figure 2). An analysis of the debates shows that China was perceived more as competitor and rival in all policy areas than as partner. This is particularly apparent in human rights, but also in security policy and geostrategic affairs. Interestingly, perhaps worryingly, attitudes even became noticeably harsher in the area of environmental and climate protection.

The Bundestag’s recent debates about China have lacked depth and variety

When the Bundestag put China on its agenda in recent years, it was solely because of lawmakers’ human-rights concerns. Beyond that, there was rarely any in-depth discussion about China. Given that the country is one of Germany's most important economic partners, it is surprising that German-Chinese economic relations played almost no role in the Bundestag. Despite China's growing global importance, the Bundestag did not engage in fundamental debate about Germany’s strategic positioning. It is hardly surprising that only a few politicians aside from human-rights experts shone with any knowledge of China.

The big question now is whether this China-critical and values-driven positioning prevalent in the Bundestag will influence the next government, especially one including Greens and Free Democrats. Taking the Bundestag debates of the last legislative period as a measure, it’s possible to assume that the new government’s attitude will be markedly different to that of the old one. But members of the Bundestag were recently focused on the issue of human rights and lost sight of other aspects of German-Chinese relations, whether economic or geopolitical. As the next government will be forced to deal with all of these issues, any predictions about Berlin adopting a sterner line with China remain speculative as a result.

Even a Scholz government could engage with China in a pragmatic way

Should the Social Democrat Olaf Scholz indeed become Chancellor, it is not unlikely that his government will continue the pragmatic, pro-business course of its predecessor. The pressure of having to ensure a day-to-day working relationship with China – above all, for economic reasons – could well force the Greens and the FDP to adjust the China stances they adopted while in opposition. The Bundestag could in the coming years again see members of the ruling parties loudly (but largely ineffectively) criticizing China – Scholz’s Chancellery engaging with China in a generally friendly manner, as Merkel’s pioneered.