Bottom-up public discourse in a top-down system

Chinese citizens can shape popular opinions and how policies are received, says Nis Grünberg. This is the last in a series of short analyses that looks at China’s systemic competition and normative rivalry with the US and the EU. A look beyond the Beijing leadership shows how far debates about the features of political systems and the power to interpret events reach into Chinese society – and possibly shape the country’s actions.

Systemic competition has become a key theme in Chinese public debates about the country’s relations with the world’s liberal democracies. A look beyond the often strongly worded statements of the Beijing leadership shows that discussions about the strengths and weaknesses of these very different political, economic and social systems are taking place throughout Chinese society. They feature the idea of China as a distinct system in an ever more tense relationship with “the West.” But, crucially, they also show that this globe-spanning rivalry is evaluated in ways by no means monolithic.

Any axiom that systemic competition automatically benefits China often remains contested outside the official discourse of Xi Jinping and the country’s leadership. This more equivocal view is palpable in debates about the nation’s drastic-but-effective Covid-19 management. Leaders and citizens like to note that it outperformed policies elsewhere, especially in the US. Beijing is keen on selling this as systemic superiority, but some scientists remain wary of such politicization. Asked whether Chinese or American vaccines were better, one simply answered: “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

Finding the balance between competition and cooperation is contentious

In technology and innovation, China’s wish – and need – for continued cooperation is flanked by scientists’ warnings about the countervailing realities of “fierce international competition”. Scientists are adamant about the value of cooperation – especially in the potentially climate-saving field of green tech – and that it must be built “on top of competition” as much as possible. But their debates are beginning to show that finding the right balance between competition and cooperation is increasingly contentious.

In addition, nativist tones are becoming more pronounced in Chinese debates about technology as they are amplified by the leadership’s emphasis on technological self-reliance in the face of systemic rivalry. As a result, cautionary tones are increasingly drowned out. A recent report by Peking University’s Institute of International and Strategic Studies that warned technological decoupling from the US would damage China was quickly taken off the internet after its publication sparked controversy online.

The view that systemic competition is not necessarily good for China is under increasing pressure. There is a marked trend towards accepting systemic rivalry as a given – and as a result adopting the stance that there is a fundamental and non-negotiable difference between the Chinese “system” and the rest of the world. This binary world view peopled by “us” and “them” has in particular been absorbed by a new public figure, one that that has traveled the world and returned to find the “Chinese model” the best.

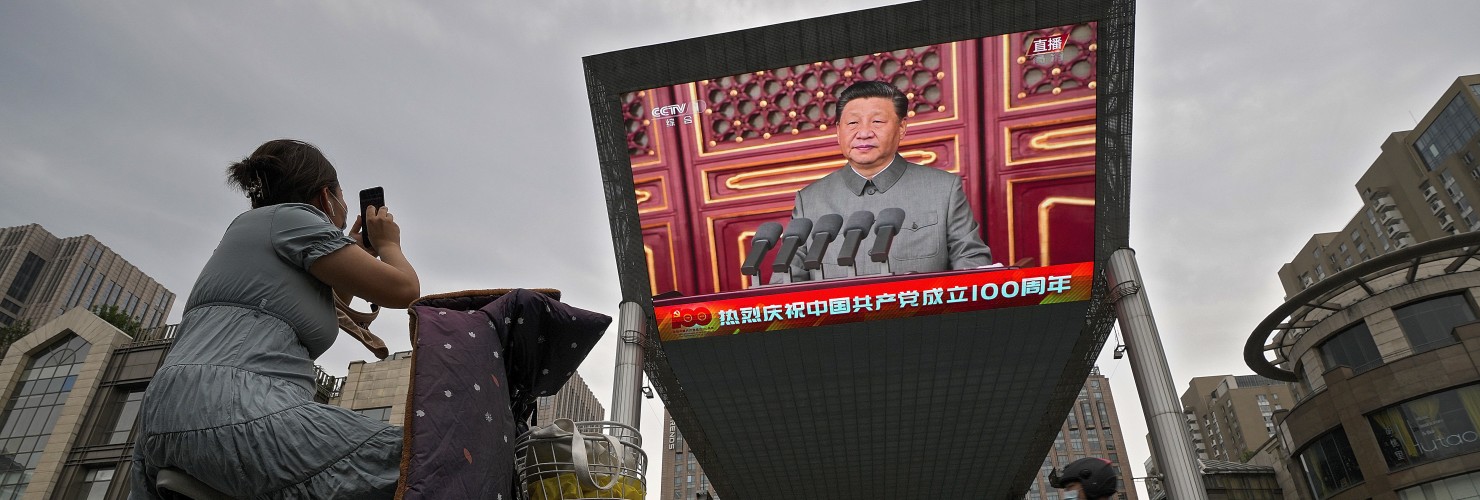

It will be interesting to see whether these Western-educated, capitalist-minded media figures and intellectuals have the power to turn a domestic debate into an international one. One of their common goals is to influence “thinking in the West about the world and about itself” and to promote Communist Party-led China as an alternative way. They are using their influence to promote patriotic messages, often officially sanctioned ones, on domestic state-run media – and on social media both at home and abroad.

Debates about the Chinese model and rivalry with other systems has a long history in China. In 1996, the bestseller “China can say no” revealed a new nationalist, anti-American view was popular among well-educated Chinese (even if Beijing condemned the book). In 2009, “Unhappy China” went further, claiming the country had to aspire to hegemony to have the world accept it on equal terms. China had just hosted the successful Olympics and watched capitalism almost unravel in the global financial crisis. Song Qiang, one of the authors, proclaimed: “China is capable of leading the world.”

Nationalism has become part of the CCP’s core repertoire

On both occasions, China’s leaders held back. Nationalism seemed a hard-to-control weapon – and could even potentially be used against Beijing. Since then, however, it has become part of the Chinese Communist Party’s core repertoire – in the form of the “core socialist value” of “patriotism.” What is striking about most of today’s popular debates taking place beyond the Beijing leadership is their alignment with official messaging. Censorship and media control are no doubt reasons for this. But an increasing number of discussions appear to accept systemic competition as a given.

But many debates in China do remain diverse. Top-level discourse is a major factor shaping domestic debates from the top down, but there are also debates that exert an influence from the bottom (or middle) upwards. When the initially rather diffuse concept of “common prosperity” was introduced, influential Chinese commentators, foreign observers, and Chinese economists and former officials were only too keen to chime in with very different takes on the meaning of Xi’s new flagship slogan.

While the leftist blogger Li Guangman called for a “profound revolution” to correct the distortions of capitalism and do more to help the “common workers,” Hu Xijin, a former editor-in-chief of tabloid Global Times, warned such rash appeals would only “stir up confusion and panic.” Common prosperity would not be achieved by inciting “any revolution,” he said, more gradual improvements to the current system were necessary. The debates led Xi to dampen the more drastic takes on his concept. “The common prosperity we desire is not egalitarianism,” he said. It was by no means a “free lunch.”

Xi’s intervention was rare and illuminating. It showed that even in a top-down system, wider debates about policy signals are important – officials and leaders listen to the debates taking place around them, even if this is seldom visible to outsiders. Local and regional officials, scientists, influential media personalities and business leaders can shape opinions and policy reception, they can have an impact, in particular at sub-national levels. It is increasingly important to understand this aspect of public discourse in China – and that demands an awareness of public input beyond Beijing’s mantras.

Acknowledgements

This analysis is part of a series supported by a Ford Foundation grant and is licensed to the public subject to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.