The CCP in 2021: smart governance, cyber sovereignty and tech supremacy

by Katja Drinhausen and John Lee

You are reading chapter 2 of the MERICS Paper on China "The CCP's next century: expanding economic control, digital governance and national security". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading chapter 2 of the MERICS Paper on China "The CCP's next century: expanding economic control, digital governance and national security". Click here to go to the table of contents.

Key findings

- Achieving greater technological self-reliance is integral to the CCP’s vision for the digitalization of China, and Chinese authorities continue to extend and calibrate their control over the internet.

- China’s government has embraced digitalization of government services, leapfrogging developments in many Western states.

-

China’s government has built a solid foundation of digital infrastructure. Citizens and private sector have seen tangible gains; a flourishing digital economy, better access to goods and improved public services.

-

The CCP’s hope is that digital technologies can proffer new access channels to public goods and ultimately bolster its legitimacy.

- Its all-encompassing understanding of national security extends to cyber and cultural security, where the focus is on cleansing China’s internet of ideas and information that might be harmful to the party’s hold on power.

- The CCP’s challenge is to keep open international channels for technological imports and exchanges in the face of growing tensions with advanced economies.

1. Devising an institutional system for managing digitalization

For two decades, the CCP’s top leaders have recognized that “informatization” – the application of digital technology throughout Chinese society – is key to achieving domestic development goals and improving China’s position vis-à-vis the world’s leading nations. Despite former US President Bill Clinton’s prediction that trying to control the internet would be like “nailing jello to a wall,” the CCP has managed to maintain control in cyberspace, while leveraging it as a multiplier for economic growth and technological progress. The expansion of China’s internet-based economy has fueled national growth, while giving China’s authorities new tools for surveillance and censorship.

Yet the CCP’s leaders still perceive significant threats from the digital environment, eyeing the ongoing presence of foreign firms in China’s digital infrastructure, and the dominant US position in some critical capabilities. Achieving greater technological self-reliance is integral to the CCP’s vision for the digitalization of China, and Chinese authorities continue to extend and calibrate their control over a technological system, the internet, that was originally designed for a largely uncontrolled flow of information.

Under President Xi Jinping’s rule, China has devised an institutional system for managing cyberspace and the effects of digitally networked technologies across society.1 This system coordinates and oversees a rapidly expanding network of legislation, regulation and policy reaching into every area of China’s cyberspace. The CCP has successfully coopted and disciplined powerful new actors that have arisen from the digital economy, notably China’s internet platform businesses, while policing and mobilizing the masses online. The activities of foreign entities are not exempt from this oversight and control.

Leadership in key digital technologies and applications coupled with control over information transmitted through cyberspace, is seen as central to economic and systemic competitiveness. The Chinese government has rapidly driven forward the country’s network expansion. The number of Chinese internet users is set to cross the one billion mark in 2021, or a penetration rate of more than 70 percent. Chinese citizens now account for one fifth of global internet users.2 The leadership strives to stay at the forefront of new technological developments. China’s telecoms operators had installed around 819,000 5G telecoms base stations by May 2021.

Life in China has gone digital during the last decade, as services, sales and payments have moved online. Chinese tech companies have flourished in this environment: China’s internet companies are among the biggest global players. Xiaomi alone claimed to have 325 million smart home appliances connected to its proprietary Internet of Things (IoT) platform by the end of 2020. Using “top-level design,” an approach of guiding policy from the pinnacle of party-state authority, the CCP aims to control and harness economic digitalization and the internet for its goal of “socialist modernization and national rejuvenation.”

2. Generating support for CCP-rule through smart governance

Digitalization and informatization remain key items on China’s political agenda, with the explicit goal of using big data to modernize national governance. The 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025), adopted by the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March 2021, is supposed to usher in a new chapter of smart and modern Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule.3 Building on the “Internet+”-strategy established in the previous five-year plan it focuses on leveraging information and communication technologies (ICT) to improve governance efficiency across sectors.

The CCP’s hope is that digital technologies can proffer new access channels to public goods and ultimately bolster the Chinese people’s trust in the party and its leadership. Whether in poverty reduction, basic services or public security, digital technologies are expected to contribute to sustainable economic and social development. For instance, smart cities are designed to help manage urban areas sustainably – an urgent topic given the sheer number of large cities in China, all of which use vast amounts of scarce resources such as water and energy, and struggle with transport and social infrastructure bottlenecks due to high population density.4

Rural digital infrastructure and literacy still notably lags behind urban areas. The government plans to expand access to internet services and e-commerce platforms as well as training in rural areas to promote economic growth and consolidate its poverty reduction achievements.5 Even if rural residents won’t turn into online entrepreneurs overnight, this has already provided faster and cheaper access to goods.6

Digitalization is also intended to accompany institutional reforms in the areas of social security and health. For example, a new digital social security card has been developed and has already been issued to over 460 million citizens, allowing easier access to benefits across regions – addressing a key challenge for China’s large domestic migrant population of more than 200 million.7

Under the “Healthy China” strategy of 2015, a national information system has been rolled out. E-services and online consultations are intended to better connect doctors and patients, counteract the uneven regional distribution of medical care, and make healthcare more cost-efficient.8 This task can only become more urgent, as China’s population is aging rapidly due to the one-child policy.

China’s government has embraced digitalization of government services, leapfrogging developments in many Western states. A national e-government system has been in the works since 2016. The new Five-Year Plan sets further goals for expansion. The aim is to offer a wide variety of services online and ensure that citizens “do not have to appear in person more than once”. Identity verification is increasingly offered online via digital ID or face recognition, implying significant time savings for users given the great distances often involved.9

A number of cities, such as Fuzhou, have developed comprehensive local service apps to facilitate everything from buying tickets for local public transport, managing social security accounts and starting a business, to paying for doctor's visits, electricity or other services.10

Data-driven solutions are seen as essential for streamlining bureaucracy. China’s leadership believes far reaching-digitalization will improve government agencies’ ability to identify needs and risks, and to determine who is deserving of licenses and resources. Data-sharing and integration across government agencies is emphasized, in order to generate better use of big data analysis and AI to predict and prevent risks – from economic and environmental to public health and political risks.

Since late 2019, the construction of an ecosystem of public databases has been in the works under the label of "internet + monitoring," in which diverse data points on the behavior of companies, non-governmental organizations, individuals and public institutions will be collected. The most notable example of the governments endeavors is China’s Social Credit System, which tracks the compliance of individuals, companies and institutions with laws and regulations under unified identification numbers.11

The party-state sees data, including personal data, primarily as a resource for governance and the promotion of economic development. Despite the massive amounts of data collected, privacy and data security issues have been insufficiently addressed. Excessive data collection and leaks by companies and public administrations have caused public discontent. In a 2019 survey, more than 77 percent of internet users reported being affected.12

The government is taking steps towards greater regulation. China’s first Personal Information Protection Law as well as new privacy and data security regulations and restrictions on the use of facial recognition and AI are in the making. However, they can be expected to continue to mainly target the private sector. Government departments will have to adhere to higher standards, but still face less stringent restrictions on what they can collect and share.13 Most importantly, laws and regulations allow for broad national and public security exemptions.

3. Harnessing digital technologies for political control

Safeguarding national and regime security remain top of the CCP’s political agenda. China’s all-encompassing understanding of national security extends to cyber and cultural security, where the focus is on cleansing China’s internet of ideas and information that might be harmful to the party’s hold on power. To implement its political project, the CCP deploys technologies that were long conceived in Western countries as fostering pluralistic debate and potential drivers of political liberalization.

Social stability and regime security is seen as resting on the state’s competency and capacity to monitor and censor. From the mid-2000s, China has gradually shut out the major international communication and media platforms from its market. Chinese companies have flourished, developing their own innovative products while offering the state a high degree of control over content.

To be economically successful and retain market share, Chinese companies must comply with regulatory demands and institutional supervision; for instance, in-house CCP committees, licensing procedures and content review. These factors ensure that platforms self-govern in the desired direction and build products and services that only allow for controlled civic engagement.14

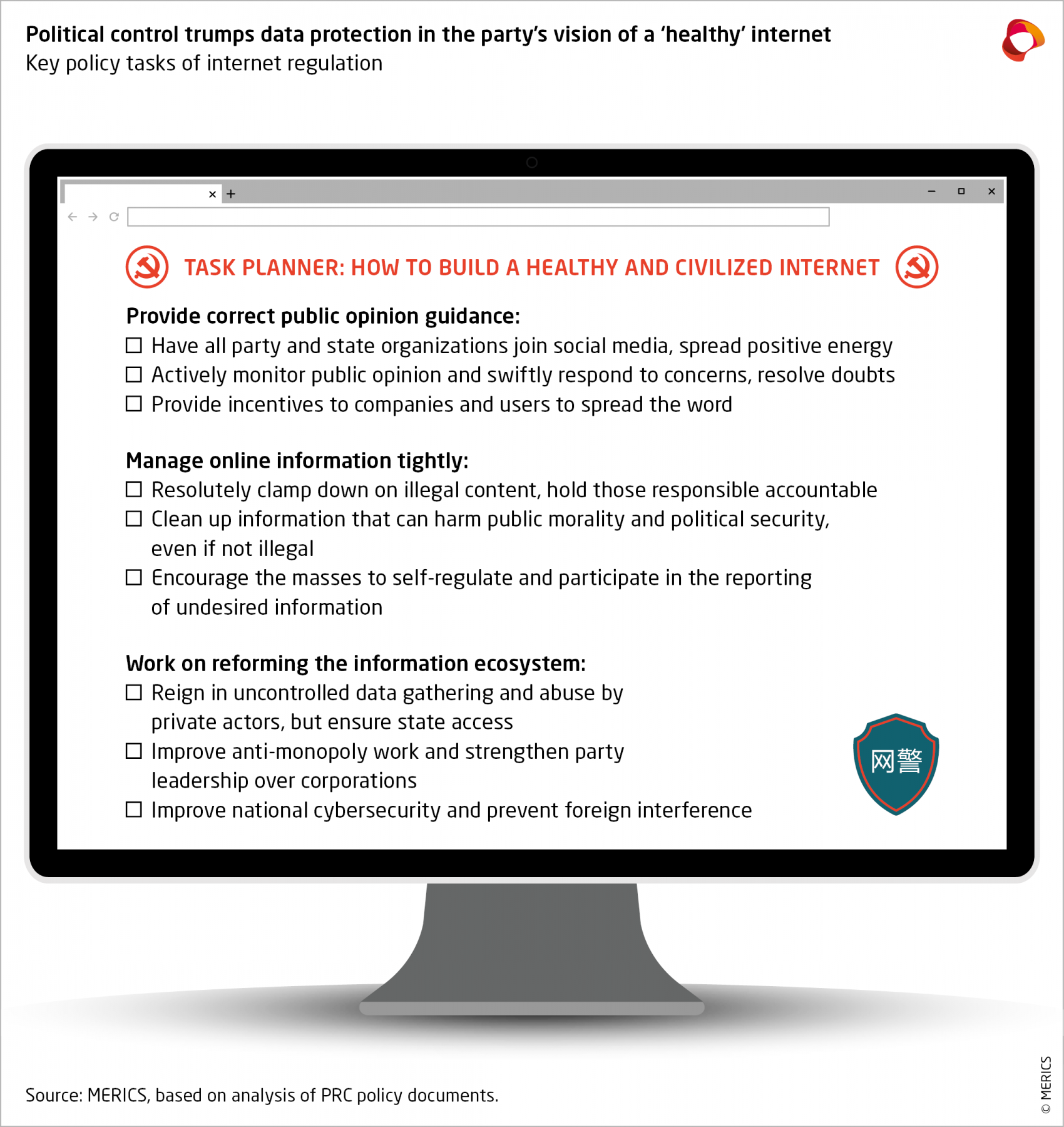

The CCP is particularly concerned about the viral dissemination of information critical of the government and spill-over effects that might result in protests or political movements offline.15 A core component of media policy under Xi has therefore been building a “healthy internet” in which negative information is contained and “positive energy” is spread by state actors. In recent years, a lengthy series of laws and regulations for content control in the digital space have been passed.

New regulations in January 2021 specifically targeted social media.16 Responsibility for their implementation has been put upon online media and communication platforms. A comprehensive system to detect and contain collective online actions harmful to the party is now in place. This was visible in the early information management and containment of criticism surrounding the government’s handling of the outbreak of the pandemic.17 No such limitations are placed on outbursts of nationalistic fervor, as visible in the boycott calls against international companies.18

The party state not only wants to monitor, shape and contain online behavior, it aims to monitor and control citizens’ offline behavior, too. Over the past decades, it has built a layered system of monitoring and surveillance platforms.19 A key indicator is the growing number of safe cities and residential communities. These reflect an intent to improve social governance, with a heavy emphasis on ensuring “social stability.”

Most public spaces are covered by cameras - not just streets and train stations, but also buses and taxis, schools and universities, places of religious worship, bars and restaurants. Train and long-distance bus journeys are only possible with real name registration and identity checks.

China now boasts the world’s most comprehensive surveillance coverage. Facial recognition is being widely applied in practice and development of smart, AI-driven policing encouraged. China’s success in containing Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted this comprehensive coverage and has domestically legitimized widespread surveillance.

The intensity of control is highest in minority regions such as Xinjiang and Tibet, where the distinct identities of ethnic and religious minority groups are seen as a latent threats to state security. Measures in Xinjiang include, for example, the forced installation of spyware and continuous monitoring of mobile devices. It also entails the use of various apps through which cadres and other public personnel feed information into multiple databases, most notably the Integrated Joint Operations Platform.

The platform has been built over the past five years to integrate and assess information about individuals from ethnic and religious minority groups. The collected data is used to identify behavior that deviates from state-defined norms. Rooted in highly discriminatory state perceptions, the use of technology has contributed to wide-scale extra-legal detention of more than a million people since 2016 and significant restrictions on freedom of movement and expression in Xinjiang and beyond.20

A key characteristic of China’s growing surveillance state is how it connects with and supports long established offline capacities in monitoring and policy enforcement. Public security personnel, party officials and residential community workers are tasked with maintaining a social stability. In pursuit of their goal, they make use of digital solutions to enter information and help enforce policy, identify risks, resolve issues and prevent protests. In addition, numerous apps and platforms seek to mobilize citizens to, for instance, alert authorities to suspicious behavior or report ideological failings, such as an “incorrect” understanding of the party and its historical contributions.

Automation levels within the various surveillance initiatives, especially those that are partly locally-built, often remains relatively low. However, China’s government is pushing for joint standards and better integration of data sources.

4. Closing gaps to achieve a secure and controllable digital ecosystem

The CCP’s top leaders recognize that to secure this vision of a digitalized China, they must achieve greater independence in the technologies that constitute cyberspace. As foreign governments place more restraints on China’s freedom to import ‘core technologies’, ensuring that Chinese firms are capable of producing these for themselves has become a first-order priority.

However, the CCP also seems to have grasped that the complexity of new technologies and the globally connected nature of the digitalized economy make complete autarky neither realistic, nor desirable. The goal is to reshape global economic and technological systems and supply chains increasingly on China’s terms.

The PRC’s techno-nationalist tradition of seeking independence in key technologies dates from the Mao era, when it was focused on strategic weapons.21 As China opened up from the 1980s onwards, the CCP began instituting policies to catch up with advanced economies. Policies sought to foster indigenous development of technologies that were seen as vital for economic competitiveness and military competition, and to address the global shift in technological innovation from defense to civilian industry.22

Since coming to power, Xi has stressed that China’s “greatest hidden danger lies in core technologies being under the control of others.”23 China’s last five-year science and technology innovation plan (issued in 2016) emphasized growing the nation’s capacity for independent innovation, and national policy initiatives like ‘Made in China 2025’ were aimed expressly at import substitution and industrial upgrading.24

The urgency of boosting domestic technical capacities has increased with expanding US export controls and other measures that target leading Chinese digital technology firms, such as Huawei, and technology exchanges with China in general. These imperatives combined with the Covid-19 global economic slump have led the party-state to redouble efforts to accelerate development of Chinese capabilities along all segments of technological supply chains and applications.

The focus is on technologies that support the national roll-out of digital “new infrastructure,” such as 5G telecoms networks, and frontier technologies such as artificial intelligence.25 The CCP’s ‘Fifth Plenum Proposal’ of October 2020, in anticipation of the 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025), declared that self-reliance in science and technology was a “strategic support” for national development and gave innovation a “core position” in the national modernization project.

The CCP’s challenge is to keep open international channels for technological imports and exchanges in the face of growing tensions with advanced economies while boosting domestic capabilities to develop and build core technologies. Internally, greater self-reliance is being pursued by stimulating self-contained domestic economic activity (“dual circulation”) while making foreign technology providers conform increasingly to Chinese rules (“secure and controllable”).

This aims to address the threat of foreign state intervention in China’s digital networks which has exercised China’s leaders ever since Edward Snowden revealed the extent of US government cyberspace capabilities and their potential exploitation of private US technology providers.

Chinese firms are increasingly turning to domestic suppliers to mitigate the risk of losing access to foreign inputs. This will raise the level of self-sufficiency in China’s domestic technological ecosystems. For instance, Huawei has reacted to targeted US pressure by cultivating domestic industry partnerships and investing in smaller firms that show potential to substitute for foreign vendors.

Efforts to develop domestic capabilities despite US export controls also benefit from the willingness of firms from other advanced economies to replace US vendors. However, in some areas US supply chain dominance is so pronounced that it is hard to circumvent over the short term.

Even as the party state tightens its surveillance and control over China’s cyberspace, it still accommodates the developmental imperative for cross-border flows of information. For example, trial projects to facilitate international data transfers are being developed in pilot zones around China at the central authorities’ direction.26

Xi Jinping recently reiterated the need to ‘proactively integrate’ China into global science and technology networks. The CCP’s long-standing, pragmatic approach of “crossing the river by feeling the stones” can be expected to inform future efforts to reconcile its seemingly contradictory goals of control and interconnectedness in a digitalized society.

These contradictions are unlikely to be resolved by 2035. However, from the party’s viewpoint the risks to control can be mitigated by leveraging the two-sided nature of interdependence; as Xi has put it, by building structural dependence on China into global production chains.27 The willingness of foreign interests to continue investing and, increasingly, to locate research and development operations in China has likely reinforced the viability of this approach to the CCP leadership.

5. ICT is not a fail safe for securing China’s and the CPP’s future

China’s leadership takes a two-pronged approach to using ICT in domestic governance. To strengthen is legitimacy, the party state invests in efficiency and better services, while building up capacities to safeguard its hold on power. China’s government has built a solid foundation of digital infrastructure. Despite domestic criticism surrounding data privacy risks and digital barriers for the elderly, disabled, or poor, China’s citizens and private sector have seen tangible gains; a flourishing digital economy, better access to goods and improved public services. Digital solutions will continue to be used to improve governance efficiency in the coming years – including their application for repressive policies such as censorship and surveillance.28

In Beijing’s eyes, it is pioneering the future of modern governance, based on centrally guided and constant monitoring, surveillance and assessment. This assessment has become part of the growing discourse within China of systemic competition, which sees “chaos in the West and order in China” (西方之乱,中国之治).29

China’s data- and technology-driven governance model is contrasted with the outdated Western approach to governance; centered on the rule of law and independent supervision of state power through the separation of powers, press freedom and civil society. The government has adeptly framed its pandemic containment successes as a direct result of its systemic advantage.30

Despite Beijing’s narrative of China’s superior model of governance, the sheer amount of resources that are being invested to detect and contain perceived threats to stability and regime security tells another story. China’s growing surveillance infrastructure is an indicator of what the party state fears will happen if it cannot control its people and the various societal stakeholders. It is a costly undertaking. According to a recent analysis by the Jamestown foundation, the Chinese government spent around USD 6.6 billion on censorship in 2020.31 Building this tight security network swallows public funds that could be spent on addressing root causes of discontent – for instance social inequality, rising living costs and gaps in the education and welfare system.

The leadership’s security-focused domestic approach also has international implications. The party state has identified data that it sees as politically necessary and taken steps to guarantee access to it. This includes legally mandating access rights for state organs and setting strict data localization requirements. China’s integration into the international digital economy is therefore impeded by difficulties for Chinese and foreign actors wanting to transfer data across borders. Pilot programs for special international data transfer rules in free-trade zones around China can only partly alleviate this issue.32

Broad “national security exemptions” permitting the state to demand information have also harmed the perception and opportunities of Chinese companies abroad. Increasingly, Huawei, ZTE, Bytedance and others are met with suspicion and regulation.33 The trend is being exacerbated by the tarnished reputations of companies which have taken part in the suppression of dissent and discrimination or violated the human rights of ethnic and religious minorities.34

China faces significant obstacles to closing the gap with global industry leaders in core digital technologies. In many supply chains for sophisticated digital technologies, more complex inputs and intellectual property rights are often still dominated by US firms or those of US allies. Yet despite mounting pressure on China’s access to cutting-edge research and overseas products and processes, there are only limited signs of a potential coordinated technological blockade against it, even among technologically advanced liberal democracies.

China’s internal economy and innovation system is now probably capable of self-sufficiency in most fields, albeit at performance levels that trail behind trailing global industry leaders. If Chinese firms were faced with coordinated “decoupling” in digital technology by the US and its allies, they would still probably not be confined to domestic markets, given their extensive international presence and influence in emerging technological ecosystems. Much growth in the global digital economy is occurring in regions where China’s economic influence is relatively strong. For example, Southeast Asia’s digital economy is projected to triple in value to 300 billion USD by 2025.35

The CCP’s leadership has made clear that, even as it extends its control over China’s cyberspace, it still seeks to both shape and adapt to the global digital economy. For example, the government recently issued directions to promote greater harmonization of Chinese technical standards with international ones. Chinese actors remain engaged in international cyberspace governance and technical standards-setting processes for digital systems.

At home, China is building a resource-intensive but effective system of digitally enabled social control and governance. Abroad, it is building a national profile in the integrated global digital economy, in which it currently remains internationally competitive. For the CCP to realize its 2035 goals, its ability to reconcile this model with growing external pressures for digital “decoupling” will be critical. It is proceeding through playing technological catch-up with foreign industry leaders and by trying to keep open key foreign markets and partnerships in the face of political pressure from the US government and other quarters.

- Endnotes

-

1 | Creemers, Rogier (2021). “Report: China’s Cyber Governance Institutions”. LeidenAsiaCentre. January 5. https://leidenasiacentre.nl/en/report-chinas-cyber-governance-institutions/. Accessed: May 17, 2021.

2 | Xinhua (2021a). “中国网民逼近10亿,意味着啥 (China's netizens approach one billion: what does this mean?)”. February 18. http://www.xinhuanet.com/info/2021-02/18/c_139749373.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021; China internet Network Information Center (2019). “第43次《中国互联网络发展状况统计报告》 (The 43rd China Statistical Report on internet Development)”. February 28. http://www.cac.gov.cn/2019-02/28/c_1124175677.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

3 | State Council (2018). “Internet Plus: a life-changing initiative”. January 21. http://english.www.gov.cn/premier/news/2018/01/21/content_281476021268046.htm. Accessed June 7, 2019.

4 | Fan Yang (2018). “China’s Big Brother smart cities - Can the law protect the privacy of Chinese citizens?” July 26. https://www.policyforum.net/chinas-big-brother-smart-cities/. Accessed: May 8, 2019.

5 | Xinhua (2021b). “中华人民共和国国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划 (14th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China)”. March 13. http://www.xinhuanet.com/2021-03/13/c_1127205564.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

6 | Couture, Victor, Benjamin Faber, Yizhen Gu, and Lizhi Liu (2021). “Connecting the Countryside via E-Commerce: Evidence from China”. American Economic Review: Insights 3(1): 35-50.

7 | China News (2021). “全国社保卡持卡人数13.4亿 社保基金累计结余6.4万亿 (The number of social security card holders nationwide is 1.34 billion, the cumulative balance of social security funds is 6.4 trillion RMB)”. April 26. https://www.chinanews.com/gn/2021/04-26/9464151.shtml. Accessed: May 25, 2021; Cankao Xiaoxi (2017). “预计2020年中国仍有2亿左右流动人口 (It is estimated that by 2020, China will have a floating population of around 200 million)”. February 14. http://www.cankaoxiaoxi.com/china/20170214/1687552.shtml. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

8 | Stepan, Matthias and Jane Duckett (2018). “Serve the people - Innovation and IT in China’s social development agenda”. MERICS Paper on China. October 18. https://merics.org/en/report/serve-people. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

9 | Cyberspace Administration of China (2018). “六成网民使用线上政务办事,政务新媒体助力政务服务智能化 (Sixty percent of netizens use online government affairs, and new government media helps intelligent government services)”. January 31. http://www.cac.gov.cn/2018-01/31/c_1122341540.htm Accessed May 15, 2019.

10 | Xinhua (2019). “China eyes digital technologies to cut red tape”. May 3. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-05/03/c_138032017.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

11 | Drinhausen, Katja and Vincent Brussee (2021). “China’s Social Credit System in 2021: From fragmentation towards integration”. MERICS China Monitor. March 3. https://merics.org/en/report/chinas-social-credit-system-2021-fragmentation-towards-integration. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

12 | Xinhua (2020). “防信息泄露,拒做透明人 (Prevent information leakage, refuse to be a ’transparent person’)”. December 7. http://www.xinhuanet.com/2020-12/07/c_1126828874.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

13 | Horsley, Jamie P. (2021). “How will China’s privacy law apply to the Chinese state?” January 26. https://www.newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/digichina/blog/how-will-chinas-privacy-law-apply-to-the-chinese-state/. Accessed: May 17, 2021.

14 | Brussee, Vincent (2020). "Designed for Censorship”. MERICS Short Analysis. July 28. https://merics.org/en/opinion/designed-censorship. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

15 | Godement, Francois et al. (2018). “The China Dream Goes Digital: Technology in the Age of Xi”. European Council on Foreign Relations. October 25. https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_china_dream_digital_technology_in_the_age_of_xi/. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

16 | Hu, Minghe and Iris Deng (2021). “China Updates Rules on Social Media Accounts, Increasing the Already High Cost of Moderation”. January 25. https://www.scmp.com/tech/policy/article/3119134/china-updates-rules-social-media-accounts-increasing-already-high-cost. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

17 | Cook, Sarah (2020). “Coronavirus Cover-ups, Disinformation, Netizen Pushback”. Freedom House China Media Bulletin 143. https://freedomhouse.org/report/china-media-bulletin/2020/coronavirus-cover-ups-disinformation-netizen-pushback-april-2020. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

18 | New York Times (2021). “How China's Outrage Machine Kicked Up a Storm Over H&M”. March 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/29/business/china-xinjiang-cotton-hm.html. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

19 | Batke, Jessica and Mareike Ohlberg (2020). “State of Surveillance - Government Documents Reveal New Evidence on China's Efforts to Monitor Its People”. ChinaFile. October 30. https://www.chinafile.com/state-surveillance-china. Accessed: May 25, 2021; Peterson, Dahlia (2020). “Designing Alternatives

to China’s Repressive Surveillance State.” CSET Policy Brief. https://cset.georgetown.

edu/research/designing-alternatives-to-chinas-repressive-surveillance-state/. Accessed: November

6, 2020.20 | Human Rights Watch (2019). “China's Algorithm of Repression - Reverse Engineering a Xinjiang Police Mass Surveillance App”. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/china0519_web5.pdf. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

21 | Feigenbaum, Evan A. (2003). China's Techno-Warriors: National Security and Strategic Competition from the Nuclear to the Information Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

22 | Naughton, Barry (2021). The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy, 1978 to 2020. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

23 | Xi, Jinping (2016) “Speech at the Work Conference for Cybersecurity and Informatization”, translated by Rogier Creemers. April 19. https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2016/04/19/speech-at-the-work-conference-for-cybersecurity-and-informatization/. Accessed: 17 May, 2021.

24 | State Council (2016). “国务院关于印发“十三五”国家科技创新规划的通知 (Notice of the State Council on Issuing the ’13th Five-Year Plan’ National Science and Technology Innovation Plan)”. June 28. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-08/08/content_5098072.htm. Accessed: 17 May, 2021.

25 | Ockel, Laura (2020) “New Chinese Ambitions for 'Strategic Emerging Industries,' Translated” September 29. https://www.newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/digichina/blog/new-chinese-ambitions-strategic-emerging-industries-translated/. Accessed: 17 May, 2021.

26 | Ministry of Commerce (2020). “商务部关于印发全面深化服务贸易创新发展试点总体方案的通知 (Notice by the Ministry of Commerce on Issuing the Overall Plan for Comprehensively Deepening the Pilot Program for the Innovation and Development of Trade in Services)”. August 12. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-08/14/content_5534759.htm. Accessed: 17 May, 2021.

27 | Xi Jinping (2020). “国家中长期经济社会发展战略若干重大问题 (Major issues with the national medium and long-term economic and social development strategy)”. April 4. http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2020-10/31/c_1126680390.htm Accessed: 17 May, 2021.

28 | Xinhua (2021b); China internet Network Information Center (2021). “第47次《中国互联网络发展状况统计报告》 (The 43rd China Statistical Report on internet Development)”. February 3. http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-02/03/c_1613923423079314.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021; Ni, Vincent and Yitsing Wang (2020). “How to Disappear on Happiness Avenue in Beijing”. BBC. November 24. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-55053978. Accessed: May 25, 2021; Mai, Jun (2021). “China Deletes 2 Million Online Posts for ‘Historical Nihilism’ as Communist Party Centenary Nears”. SCMP. May 11. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3132957/china-deletes-2-million-online-posts-historical-nihilism. Accessed: May 25, 2021; People’s Daily (2021). “世界电信日:中国5G“扬帆起航” 赋能千行百业高质量发展 (World Telecommunications Day: China’s 5G ‘sets sail’ to empower the high-quality development of thousands of industries)”. May 17. http://finance.people.com.cn/n1/2021/0517/c1004-32105213.html. Accessed: May 25, 2021; CCTV (2020). “2020年新增58万5G基站 覆盖所有地市 (580.000 new 5G base stations have been installed in 2020, covering all places and cities)”. December 24. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/24/content_5573126.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021; STCN (2019). “集成电路产业利好!国家大基金二期募资完成,规模2000亿左右 (The integrated circuit industry is favourable! The second big fundraising for the national key fund has been completed, with a scale of around 200 billion RMB)”. July 26. http://news.stcn.com/2019/0726/15277294.shtml. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

29 | Zhang, Weiwei (2017). “西方之乱与中国之治的制度原因 (The institutional causes of the west's chaos and China's order)”. August 2. http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2017-08/02/c_1121422337.htm. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

30 | Wang, Mengjie (2020). “China's Governance Model in Response to the Coronavirus Outbreak”. February 20. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-02-20/China-s-governance-model-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-outbreak-OcLTh8x9u0/index.html. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

31 | Fedasiuk, Ryan (2021). “Buying Silence: The Price of Internet Censorship in China”. Jamestown China Brief 21(1). https://jamestown.org/program/buying-silence-the-price-of-internet-censorship-in-china/. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

32 | German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (2020). “Policy Update on Innovative Development of Trade in Services in Pilot Areas”. September 1. https://www.plattform-i40.de/PI40/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/Publikation/China/policy-update-regulations-on-data.html. Accessed: May 17, 2021.

33 | Keane, Sean (2021). “Huawei Ban Timeline: Founder Wants to Expand Software to Make Up for US Sanctions Hit”. May 24. https://www.cnet.com/news/huawei-ban-timeline-founder-wants-to-expand-software-influence-us-sanctions/. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

34 | Whittaker, Zack (2021). “US Towns Are Buying Chinese Surveillance Tech Tied to Uighur Abuses”. May 24. https://techcrunch.com/2021/05/24/united-states-towns-hikvision-dahua-surveillance/. Accessed: May 25, 2021.

35 | Google (2020). “e-Conomy SEA 2020 Report”. https://economysea.withgoogle.com/. Accessed: May 17, 2021.