Covid-19 contact tracing apps: why they are so popular in China

Results of a cross-national online survey on public opinion towards Covid-19 contact tracing apps (CTAs) reveal that approval rates in China exceed those in western countries by a significant margin. Our guest authors Genia Kostka and Sabrina Habich-Sobiegalla of Freie Universität Berlin analyze what drives citizens’ acceptance of CTAs in different political contexts.

Contract tracing apps (CTAs) have been widely employed to combat the global spread of Covid-19. As of January 2021, the MIT Technology Review’s database on CTAs documented a total of 49 CTAs in 48 different countries. While use of this type of tool has been widespread, the specific approach taken has varied between countries.

China was the first country to try a CTA as a means of curbing the spread of the virus. In February 2020, it rolled out its “health code” app nationwide as a means of controlling people’s movements. Developed by internet giants Alibaba and Tencent, users access the app through Alipay or WeChat and input their phone number, full name and ID number.

After registration, the health code used self-reported travel histories or any suspect symptoms and automatically collected travel and medical data to assign users a red, yellow or green QR code. Whereas a green code gave users unhindered access to public spaces, a yellow code indicated that the person might have come into contact with a person with Covid-19 infection and therefore has to be confined to their homes or an isolation facility. A red code was assigned to users infected with the virus.

As public spaces like shopping malls can only be accessed with a green QR code, installation of the health code app became to all intents and purposes mandatory in China, resulting in broad adoption of the app among Chinese citizens. The app received criticism, however, for collecting a wide range of information on central servers including personal information, location, recent contacts, health status and travel history.

By contrast, Germany launched its “Corona-Warn-App” much later, on June 16, 2020, after a long-drawn discussion about data privacy issues and the related design of the app. The download of the app in Germany is voluntary, and information exchange takes place locally on people’s phones without collecting information on a central server about personal identities or locations.

In the United States, rather than a top-down approach by central government, states and local governments cooperated with Apple and Google to develop local apps. The apps rely on Bluetooth technology and use is voluntary. They do not collect personal information and do not upload information about personal encounters to central servers.

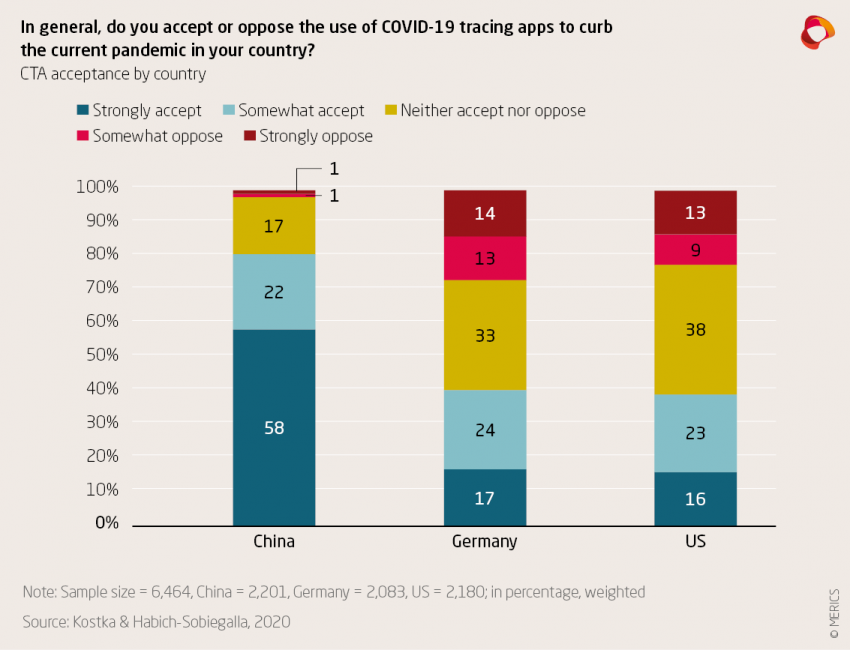

While the biggest vaccination campaign in history has started, triggering hopes for a foreseeable end of the pandemic, experts believe there will not be a return to anything like normal life until late this year. Meanwhile, CTAs remain a decisive factor in fighting the pandemic, but their efficacy depends heavily on people’s acceptance. An online survey conducted in June 2020 examined public opinions towards Covid-19 tracing apps in China (N = 2201), Germany (N = 2083), and the United States (N = 2180). The survey results show that approval ratings in China surpass those in western countries, with 80 percent of Chinese, 41 percent of German and 39 percent of United States citizens strongly or somewhat accepting CTAs. An analysis of what drives citizens’ acceptance of CTAs in these countries reveals the following significant findings.

1. Concerns about privacy violations matter

In contrast to the popularly held belief that Chinese citizens do not care about data privacy, the findings show that these concerns play an important role for citizens from all three countries. Interestingly, Chinese respondents expressed distrust towards technology companies in terms of privacy protection but seem to be more accepting of government uses of digital technologies such as Covid-19 apps, whereas in Germany and the United States the opposite appears to be the case. Partly, this could be due to ignorance of the risks associated with digital technologies, as state-led media in China offer only limited discussion of the multiple purposes for which personal data is used, including surveillance.

Compared to Germans and US citizens, Chinese cititzens are also to some extent more used to the fact that personal data is systematically collected in personalized files, a system known as “dang’an”(档案). Another possible explanation is that refusal to use technologies that are officially endorsed by the government can be difficult in China’s authoritarian context. Even though companies were responsible for the deployment of CTAs in all three countries, respondents seem to associate these apps mainly with the government which has commissioned and recommended them or made them obligatory.

2. Acceptance depends on who is identified to be capable in managing the pandemic

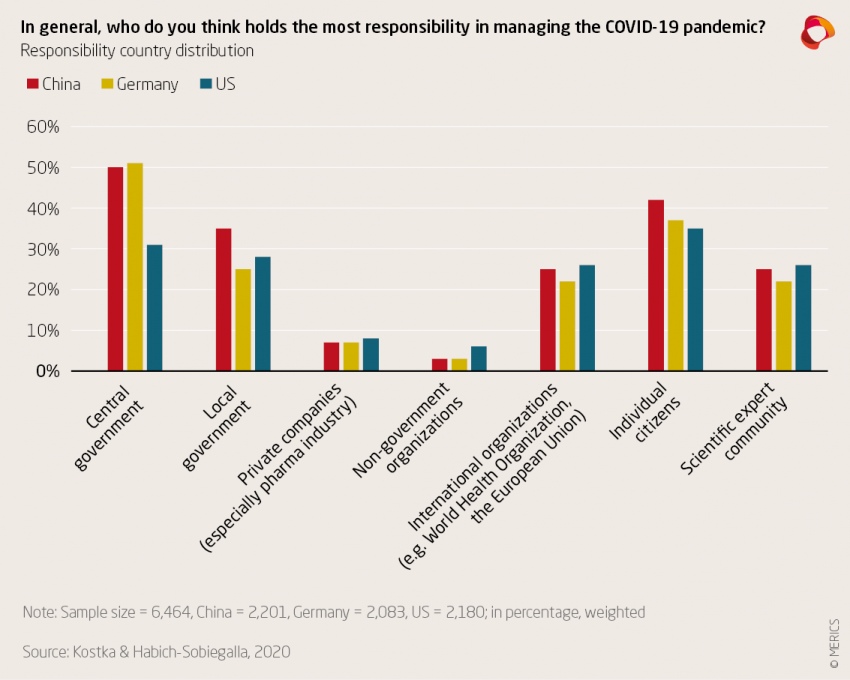

When asked who is most capable in managing the Covid-19 pandemic, the most common choices of respondents from all three countries were the central government, with 44 percent, and individuals, with 38 percent of the total surveyed. While in China the importance of the central government was emphasized over the individual, respondents from the United States believed the individual to play the key role in fighting the pandemic. The acceptance of CTAs is particular low among respondents from the United States and Germany who believe individuals, rather than governments or international organizations, have the highest competence to handle the crisis.

3. People only use CTAs if they are convinced they work

People’s assessment of the effectiveness of CTAs matters in all three countries. If people believe CTAs improve health information access, or result in fewer infections, they tend to be more likely to accept them. Perceived CTA effectiveness is higher in China than in Germany and the United States. This is likely because, first of all adoption rates in the former are much higher thereby increasing CTA effectiveness. Second, the health code app has allowed people to access public spaces in China, while in Germany and the United States CTAs are merely used for information sharing. Chinese citizens might therefore link use of the health code app to hope that their daily life can start to look normal again – with the exception of local outbreaks.

4. Trust in government is important

Acceptance of CTAs in China, Germany and the United States is highly affected by citizens’ trust in the state. The more respondents trust the state, the more likely they are to adopt the apps. Trust is particularly high in China, where 78 percent of respondents say that they trust their country’s government institutions “a lot”. This far exceeds numbers for Germany and the United States, which reach 20 percent and eight percent, respectively. However, as research on self-censorship among Chinese survey respondents has shown, these high numbers in the Chinese case must be to some extent discounted.

5. Conspiracy belief hinders CTA acceptance

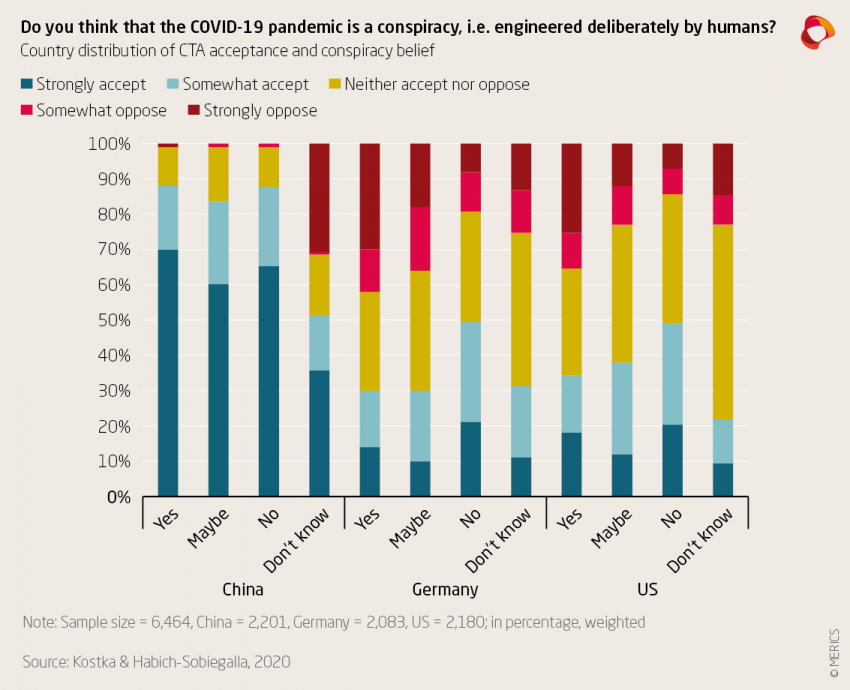

21 percent of the US respondents and 13 percent of German respondents believe that the Covid-19 pandemic is a conspiracy. This stands in contrast to a mere three percent in China. The survey analysis shows that in all three countries those who share a conspiracy belief are less likely to accept CTAs. This effect is particularly high in the case of the United States, where conspiracy theories like QAnon originated.

6. People who are technology adept are highly in favor

Around 900 respondents in China, 770 in the United States, and 600 in Germany report some experience with similar apps. Respondents who are technology adept have a higher acceptance of CTAs, suggesting that familiarity with healthcare apps positively helps with CTA adoption in the three countries.

CTAs have been quickly adopted globally, but debate about the apps’ effectiveness and desirability is ongoing. This study shows that, especially in the United States and Germany, convincing citizens to adopt CTAs continues to be important if this technology is to contain the pandemic.

About the authors:

Genia Kostka is Professor of Chinese Politics at the Freie Universität Berlin. Her research focuses on China’s digital transformation, environmental politics and political economy.

Sabrina Habich-Sobiegalla is Assistant Professor for State and Society of Modern China at the Freie Universität Berlin. Her research interests are China’s social and economic development, water and resource governance, renewable energies, development-induced displacement, and central-local relations with a focus on China.

This short analysis is based on the findings from the study 'In Times of Crisis: Public Perceptions Towards Covid-19 Contact Tracing Apps in China, Germany and the US'. For a full summary of the study, please go to SSRN.