How China imposes sanctions

A guide to the evolution of Beijing’s new policy tool

Key findings

- Geopolitical changes have led China to strengthen own unilateral sanctions. The trade conflict with the US and the sanctions imposed in 2021 by the EU, the UK, and the US for human-rights abuses in Xinjiang and the imposition of sanctions on Russia were three pivotal moments in the shaping of China’s approach to sanctions.

- The 39 cases of sanctions imposed by China between 2012 and 2023 analyzed in this report show that Chinese sanctions and countersanctions have been following a clear path.

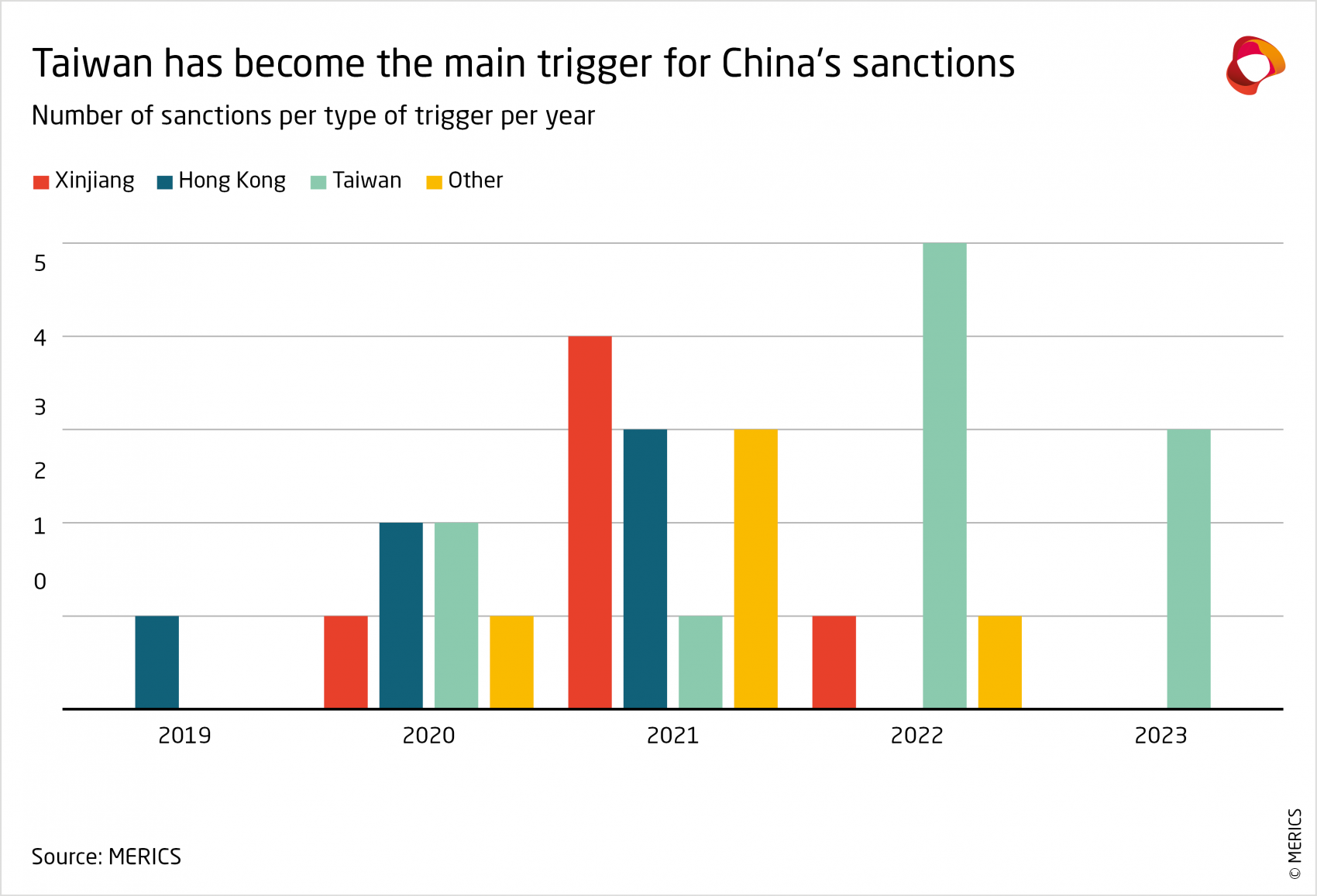

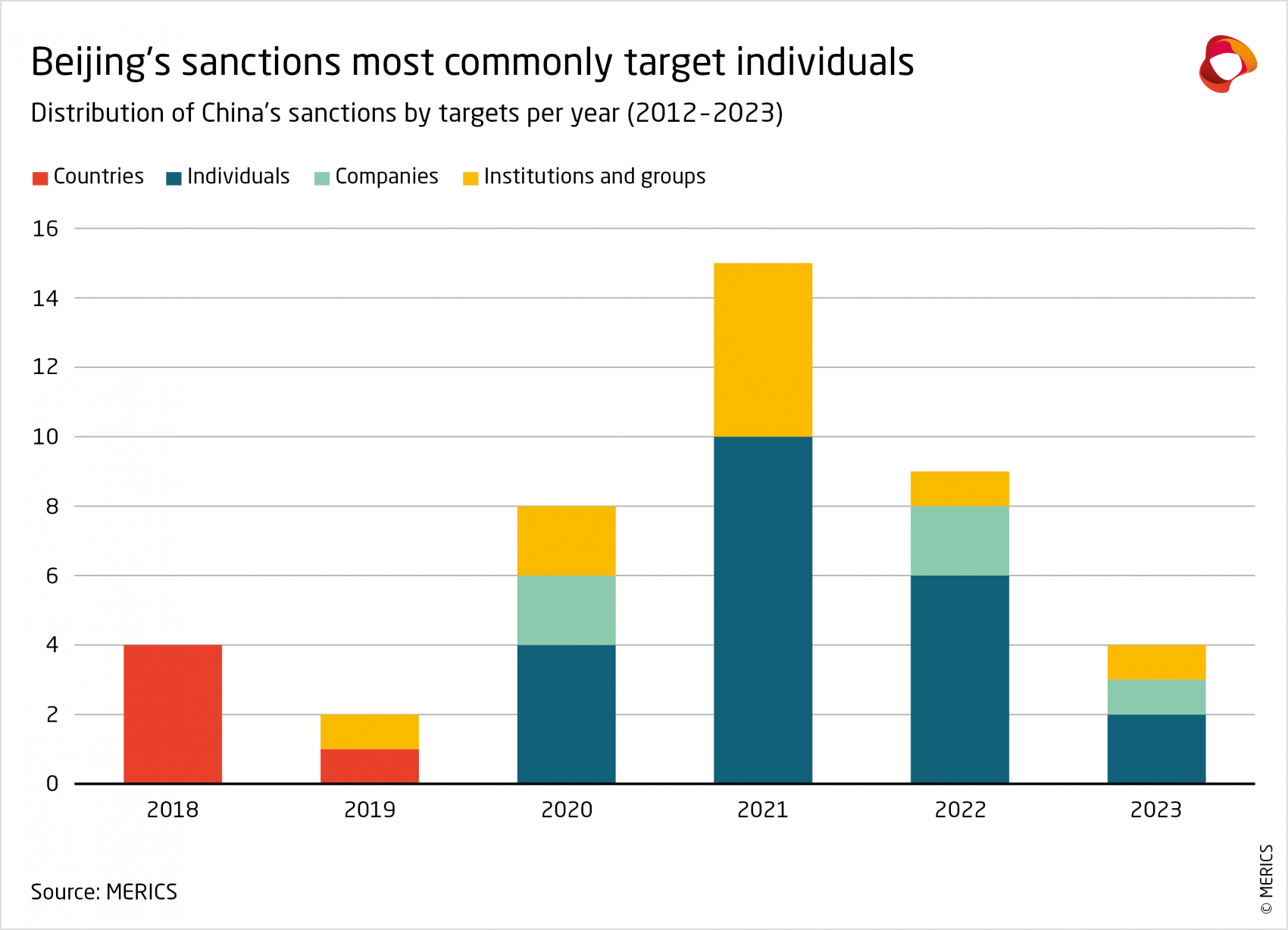

- The number of sanctions unilaterally adopted by China has risen sharply since 2018. The great majority target US individuals, groups of people or companies and have come in response to the perceived meddling in Beijing’s internal affairs, specifically Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Taiwan. This clear trend in the Chinese sanction regime is unlikely to change much in the future.

- The measures most frequently adopted are closely connected to the type of targets: asset freezes, visa bans and bans on cooperation with Chinese entities mainly target individuals; export and import controls are used for companies. China’s ability to develop financial sanctions remains limited for now, ongoing policy debates in China show a keen interest in developing a legal basis for them.

- The Unreliable Entity List and the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law are the two main policies used by China to impose official sanctions. But China’s sanctions often came as a mix of official and unofficial measures.

Introduction

As the EU considers imposing sanctions against Chinese companies that have violated the sanctions imposed on Russia, it is vital to understand how China may respond to such measures. There are two recent examples of a growing number of sanctions that China has been imposing against entities and individuals in the US and the European Union: In August 2022, China sanctioned Lithuanian Deputy Minister of Transport and Communications Agnė Vaiciukevičiūtė for visiting Taiwan. Eight months later, it sanctioned US Congressman Michael McCaul after he met Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen. It froze any assets and property he might have had in China and forbade organizations and individuals in the country from carrying out any transactions with him.

The opacity and the combination of official with unofficial sanctions feed the impression of unpredictability, which might in turn deter other actors from imposing sanctions on China to begin with. However, there is a pattern to be detected in Chinese adoption of sanctions and countersanctions.

Official sanctions have been a less prominent tool for China than its public and not-so-public attempts at economic coercion. A major reason for this is that China is a relatively new player in the unilateral sanctions game. China has only recently started developing policy tools for the adoption of sanctions. It now has a more solid legal framework to issue sanctions and countersanctions and that it imposes them much more frequently than in the past.

The trade conflict with the United States that started in 2018 was a pivotal moment, even if measures imposed by China at the time were not technically sanctions. The sanctions imposed in 2021 by the EU, the UK, and the US for human-rights abuses in Xinjiang were another milestone. China swiftly imposed countersanctions and fast-tracked the adoption of a new framework in the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (AFSL) in 2021.

The AFSL and other policies leave the Chinese leadership considerable discretion to decide when sanctions are called for, what individuals and entities will be targeted and what measures will be imposed. However, China’s unilaterally imposed sanctions show a high degree of consistency when it comes to sanctions triggers, targets and measures.

With a view to the currently increasing geopolitical tensions involving China, it is important to better understand China’s approaches to sanction-making. To add to the existing literature tracking China’s sanctions policy, this report seeks to contribute to the ongoing debate about how China’s approach may evolve by bringing together 39 cases of sanctions imposed by the central government between 2012 and 2023. The measures include six instances of sanctions adopted through the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), five cases of sanctions imposed in the course of the US-China trade conflict and 28 cases of sanctions adopted unilaterally by China.

China learns about imposing sanctions in the UN Security Council

The UNSC is the forum in which Beijing first found itself an active participant in sanctions-making. As permanent member, China has veto power over any decision put before this international body, including the adoption of sanctions. Since Xi Jinping became Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), China has continued its tradition of supporting most sanctions proposed to the UNSC. For example, in 2014 it voted in favor of resolution 2140 that imposed asset freezes, travel bans and a targeted arms embargo against “people who threaten peace and stability in Yemen”. In 2015, it voted in favor of resolution 2206 setting the same terms for actors in South Sudan.

However, China has repeatedly opposed UNSC sanctions on Iran, North Korea, Syria and fellow UNSC member Russia. Beijing’s veto power often allowed it to stop measures in preparatory negotiations, rather than at the voting stage, making it more difficult to identify its influence.

Figure one shows that China consistently backed a trickle of UNSC sanctions before adopting an ever-growing number of unilateral sanctions after the beginning of the US-China trade conflict. These measures are part of a very specific framework and need to be differentiated from other unilateral sanctions China imposed in recent years which have been adopted by China as official sanctions and “simply” as limiting measures in response to US’ own limiting measures.

Geopolitical tensions have changed China’s perception of sanctions

The trade row initiated by the Trump administration was a game changer in China’s approach to sanctions. To respond to the tariffs and export controls imposed by the US, China from 2018 to 2019 adopted a series of restrictive measures in retaliation against Washington.

Although there is an argument to be made that China has long viewed sanctions as a US geopolitical tool, its attitude towards imposing sanctions changed as the US began the trade row. If anything, the trade conflict was a symptom and an acceleration of geopolitical tensions between the US and China – and imposing sanctions became key for each side to express itself.

To this day, China’s unilateral sanctions target entities and individuals in the US far more than any other actor. To China, sanctions thus are not just about punishing the violation of international or domestic rules nor are they exclusively about signaling discontent or punishing actors who take positions that are not of Beijing’s likes. Developments during and after the beginning of the trade conflict tell us that, to China, sanctions have become a tool in the geopolitical struggle against the US in particular.

The imposition of sanctions against Russia after it attacked Ukraine spurred concerns in Beijing that it could be next. This has fueled an intense debate in China about how to improve resilience against foreign sanctions. Proposals have been tabled for a Chinese legal framework enabling the imposition of financial sanctions and anti-sanctions. However, the scenario of China imposing financial sanctions seems unlikely given the considerable legal and structural hurdles Beijing is facing.

How China developed and adopted its sanctions toolbox

The fact that China punishes perceived infractions against its core interests is not new. However, the number of instances in which China adopted unilateral sanctions has jumped only in the past few years. Although foreign actors violated China’s interests and red lines before 2018, it did not resort to unilateral sanctions. For example, in 2009, China only cancelled an annual summit with the EU in response to the planned meeting between then French President Nicolas Sarkozy and the Dalai Lama, but at the time refrained from taking other punitive measures.

China still uses these diplomatic measures today, but it is reasonable to imagine a similar situation being met by measures such as sanctions on individuals in the French administration or the country’s companies, as it has been the case for senior US and EU officials visiting Taiwan.

The US-China trade conflict appears to have given Beijing the necessary experience and confidence to strengthen unilateral sanctions and start imposing them more frequently. In December 2019, China sanctioned five US-based non-governmental organizations (NGOs) advocating for democracy and human rights in response to US support of protesters in Hong Kong. The official reason given was that these NGOs supported “anti-China plotters who messed up Hong Kong through various means, aiding and abetting them in extreme violent criminal acts and inciting Hong Kong independence separatist activities”.

Most of the unilateral sanctions that followed the trade conflict came in response to episodes in which China perceived foreign actors to be threatening China’s national interest or crossing red lines. Many of these tend to be moveable, but matters such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Xinjiang are set items on the list of issues that will most likely spur unilateral sanctions from China in the future.

China today is more confident and capable to substitute or complement diplomatic signals or reprimands with official sanctions. The number of unilateral sanctions imposed by China has skyrocketed since 2020 – even without taking into consideration unofficial sanctions-like measures, for example, like the import bans adopted towards Australia and Lithuania.

China prefers to target single companies and individuals

China has since 2019 shown a growing preference for sanctions that target individuals, single companies, and nationwide groups or institutions, as shown in figure three. China appears to like this method because, firstly, sanctions against individuals, especially high-level figures, have a strong signaling effect and only a limited impact on China’s economy. Secondly, they can be divisive as they limit any adverse impact to the sanctioned entity and do not affect a broader group or entire industry.

That means China does not undermine the relationship with other entities and limits potential retaliation. In the end, Beijing can impose sanctions at a relatively low cost.

Notable examples of this policy include sanctions against:

- the then Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, and the Lithuanian Deputy Minister of Transport and Communications, Agnė Vaiciukevičiūtė, both of whom visited Taiwan in August 2022

- four US individuals and the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China following US sanctions against Chinese officials for the violation of human rights in Xinjiang

- eleven US individuals following the US sanctions on Chinese officials for undermining democracy in Hong Kong

- a number of US companies and individuals in October 2020 for arms sales to Taiwan (including the CEOs of the US defense companies Lockheed Martin and Raytheon)

- ten individuals and four entities in the EU, nine individuals and four entities in the UK and US and Canadian parties in March 2021 in response to Western sanctions on Chinese entities and individuals for human rights violations in Xinjiang. That list of sanctioned entities includes MERICS.

An important trait of recent Chinese sanctions is that Beijing has often not specified what measures the sanctions include. Of the 28 cases of unilateral sanctions, 12 were imposed without China disclosing any details. For example, the sanctions it imposed against EU’s entities and individuals in March 2021 do not specify exactly what these sanctions entailed.

China is filling up its sanctions toolbox

Over the course of the last decade, visa bans, asset freezes and banning cooperation with Chinese entities have become China’s most common measures of unilateral sanctions.

The US dollar’s role as the global trading currency gives Washington vast power when imposing sanctions. Is there an equivalent in Beijing’s arsenal? Arguably, China’s main strength is its large market and manufacturing productions, and thus, the strongest measure are import and other restrictions to limit or close off market access. Records of China’s unilateral sanctions show Beijing has seldom used official sanctions to impose import restrictions.

Since 2018, China has adopted import restrictions on four occasions, three of them during the trade row with the US. The other instance was in 2023, when China imposed import and investment bans on Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Technologies in response to the companies exporting arms to Taiwan.

Visa and travel bans are among the preferred measures adopted by China. Since 2018, China has imposed visa and travel bans 17 times (this includes the refusal of licenses to operate in China). For instance, the Chinese National Radio and Television Administration in 2021 declined to renew BBC World News’ annual license and banned it from broadcasting.

Bans on cooperation with Chinese entities have been adopted 14 times. The practice reached a peak in 2021, when eight sets of sanctions included bans on cooperation. An example of that would be the sanctions that China imposed in December 2021, when the US State Department and the Treasury Department announced the addition of five deputy directors of the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government in Hong Kong to the US sanctions list under the Hong Kong Autonomy Act.

Asset freezes have been adopted seven times. Most recently, they were imposed in April 2023 on actors engaging with Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-Wen during her visit to the US: Sarah May Stern, Chair of the Hudson Institute Board of Trustees; John P. Walters, President and CEO of Hudson Institute; John Heubusch, former Executive Director of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute; and Joanne M. Drake, Chief Administrative Officer of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation.

In addition, China has imposed arms embargoes four times within the framework of UNSC sanctions.

Manufacturing production is another main asset China may add to its sanctions toolbox. So far, it has imposed official export restrictions only once – against Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Technologies when it put import restrictions on the two companies.

Part of China’s economic success has been driven by foreign companies producing in the country for export. Although this in theory gives Beijing huge leverage, it has been reticent about imposing export restrictions for two reasons. China can already control exports of goods – and capital – more tightly than market economies. And its economy still relies on export production, especially in sectors with overcapacity such as iron and steel, cement, glass, aluminum, solar panels, and equipment for power generation.

China’s main policy tools: The Unreliable Entity List and the Anti-foreign Sanctions Law

China maintains a high degree of flexibility about the target and timing of sanctions, using an array of measures that may well never be communicated. To do this, it relies on its Unreliable Entity List and Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law. The two authorities mainly responsible for imposing sanctions and defining specific measures are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) and Ministry of Foreign Commerce (MOFCOM) – although both parts of the process remain difficult to trace.

The Unreliable Entity List (UEL) includes foreign entities on which China can impose limiting or punitive measures in response to behavior that is contrary to its national interest. As a response to growing number of Chinese companies being added to the US Entity List, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced the establishment of its own blacklist in 2019.

The scope and functioning of the list are described in the Provisions on the Unreliable Entity List published in 2020 by MOFCOM. For example, article 10 sets out a range of measures to punish businesses, which include fines, trade and investments restrictions and prohibitions, as well as restrictions and bans on work, entry, and residence visa. China used the newly adopted UEL for the very first time on February 16, 2023, when it included in the list two US companies: Lockheed Martin and Raytheon.

The Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (AFLS), was adopted in June 2021 after the legislative process was accelerated in response to the March 2021 imposition of sanctions by the US, EU, UK and Canada against Chinese officials and entities for the violation of human rights in Xinjiang.

The fact that Beijing was already working on the bill before the sanctions of March 2021 signal that Beijing was aware it needed to protect itself against possible foreign sanctions. However, despite the name, the AFSL is more than a policy tool to symmetrically respond to sanctions as shown by the possible targets and measures listed in the legal text. Targets include individuals and organizations directly or indirectly involved in the formulation, decisions about, or implementation of sanctions and in “discriminatory measures against Chinese citizens/interference with China’s internal affairs”.

The wide-ranging and loosely defined nature of the measures shows how China views and approaches sanctions. Any interference in what China views as internal affairs, which includes Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Taiwan, can be met with unilateral sanctions. Such a framing is not only used to justify the asymmetric imposition of sanctions, but also suggests that Beijing views the imposition of sanctions as including both official as well as unofficial sanctions. The adoption of official and unofficial policies makes it particularly difficult for other countries to track and respond to Chinese sanctions.

Sanctions according to China’s vague definitions can not only target individuals in organisations, but even their spouses and immediate family. The inclusion of families is a practice that precedes the AFSL and remains in use in the context of all Chinese sanctions. For example, the measures targeting Nancy Pelosi explicitly include “her immediate family”. In 2020, China announced sanctions on 28 US individuals for their purported interference in its internal affairs – and the sanctions were said to apply to the family members, too.

Article 12 of the AFSL introduces an element of insecurity for foreign businesses in China. It allows Chinese citizens and organizations to sue for damages individuals and organizations who implement or assist in the implementation of the discriminatory measures taken by a foreign country. However, as of April 2023, there are no records of China making use of this provision.

Article 6 of the law lists measures that can be taken: refusal of a visa to enter China, deportation from the country, banning of financial transactions and cooperation with Chinese entities, and seizure of assets. This list of measures can be expanded at any time on a case-by-case basis.

The adoption of such broad and flexible criteria in the law coupled with Beijing’s tendency not to always announce what the sanctions entail in terms of targets and measures create a climate of insecurity and unpredictability. The objective of such unpredictability may very well be to deter foreign sanctions and/or keep foreign companies in China from abiding to potential foreign sanctions.

China has applied the anti-foreign sanctions law a number of times since its adoption. For example, in July 2021, it imposed sanctions on several US individuals (including former US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross) and organizations in response to US sanctions on Chinese officials in Hong Kong.

In December 2022, China imposed sanctions against Miles Yu Maochun, principal China policy advisor on the Policy Planning Staff to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and Todd Stein, Deputy Staff Director of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China. The measures came in response to US sanctions on human rights issues related to Tibet in 2022. The two officials and close family members were banned from obtaining entry visas, had any assets they had in China frozen, and were barred from having contacts with entities in China.

The AFSL has certainly provided China with a legal framework to impose unilateral targeted sanctions and “mainstreamed” the process to do so. On the other hand, China’s selection of targets and measures has not changed noticeably from the regime before the AFSL existed.

What to watch: China’s sanction regimes will combine manifold approaches

The number of sanctions unilaterally adopted by China has risen sharply since 2018. The great majority target US individuals, groups of people or companies and have come in response to the perceived meddling in Beijing’s internal affairs, specifically Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Taiwan. This clear trend in the Chinese sanction regime is unlikely to change much in the future.

The measures most frequently adopted are closely connected to the targets: asset freezes, visa bans and bans on cooperation with Chinese entities mainly target individuals. Export and import controls are used for companies. China’s ability to develop financial sanctions remains limited for now, ongoing policy debates in China show a keen interest in developing a legal basis for them.

However, China has to date adopted unilateral sanctions that:

- came in response to perceived violations of its red lines and national interests,

- did not show any signs of any signs of adopting secondary sanctions,

- often came as a mix of official and unofficial measures (i.e., measures that are not officially announced and/or adopted by the central government).

The last point makes China’s sanctions policy challenging to respond to. Not only is litigation complicated when non-official measures are adopted, they can also bolster official sanctions, while remaining plausibly deniable. China wants to create the perception that its punitive measures are difficult to predict, in order to discourage other countries’ from sanctioning. But the patterns are visible, and keeping a close eye on China’s future behavior in devising sanctions is needed for adequate responses.