Fragmenting cyberspace: The future of the internet in China

China is one of the key drivers of the fragmentation of the internet as we currently know it. This is the key result of a new in-depth MERICS report titled “Fragmenting cyberspace: The future of the internet in China”.

Most of China’s internet services have become inaccessible for anyone without a Chinese ID and phone number. Foreign organizations and companies in the country face challenges in transferring data to their home organizations because of vague data security rules. These are just some of the barriers Beijing is creating in its pursuit of making the internet “secure and controllable”.

In the report, the authors Rebecca Arcesati, Kai von Carnap, Antonia Hmaidi and Jeroen Groenewegen-Lau analyze how fragmentation plays out across the different components of China’s internet. They zoom in on data flows, web applications, internet protocols and digital hardware as a representative cross-section of internet infrastructure.

You can read the Executive Summary and Conclusions online below or download the report as a PDF:

This report was made possible by the support of the German Federal Foreign Office.

Click here for more information on MERICS standards to maintain independence in research and editing.

Executive Summary: China as a driver of internet fragmentation

The internet as a technology and its future global development is at a pivotal moment. It is uncertain whether it can continue to connect ever-growing amounts of people and devices with minimal friction, or whether it may fragment further into a multitude of separated virtual and analog spaces and technologies. China is a major driver of fragmentation as it is creating de facto barriers in its pursuit of making the internet “secure and controllable”.

The geopolitics behind this trend is best illustrated by two declarations. Since it was issued in April 2022, the “Declaration for the Future of the Internet” has been signed by European member states, the United States, and 41 other governments.1 But not by China, which, through its State Council, published its own vision in November 2022 titled “Jointly Build a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace”.2 Whereas the “Declaration of the Future of the Internet” mentions human rights and fundamental freedoms in its opening sentence, China’s vision emphasizes security, presenting cyber sovereignty as its first basic principle.

Although the differences are clear, European member states, like most countries in the world, also regulate the internet. As a result, what people experience as the world wide web is in fact already a patchwork of many local networks. The EU can even be seen as a force of fragmentation, creating a regional network through regulations like the GDPR. There are also good reasons for Europe to raise security further, as it is increasingly being targeted by misinformation campaigns, cyberattacks and other challenges. At the same time, China’s regulations and barriers to access are more stringent and pervasive than anything European member states and the EU are implementing.

To analyze how ideological differences play out across the different components of the internet, this report zooms in on data flows, web applications, internet protocols and digital hardware, each in its own chapter. Together, these four layers provide a representative cross-section of internet infrastructure. They capture most of the trends and issues, arriving at a range of possible responses for European stakeholders.

The report distinguishes between regional discrepancies and more fundamental fragmentation.3 Regional discrepancies limit how users experience the internet but are relatively superficial. In this type of fragmentation, the internet is understood as a profoundly interconnected digital public sphere where interventions can be implemented and reversed relatively easily. The first censorship efforts through China‘s Great Firewall are an example of these regional discrepancies, as blocking the IP address of the New York Times, for instance, can be easily reversed.

A second type of fragmentation involves obstructions to the internet’s technological fundamentals. This requires complex adjustments to governance rules, technical standards, or the routing system that obstruct devices from connecting or interoperating. Such fragmentation is much harder to reverse. Throughout the different layers, China has moved beyond regional discrepancies to gradually initiate deeper incompatibilities through a mix of technical, commercial and regulatory factors.4

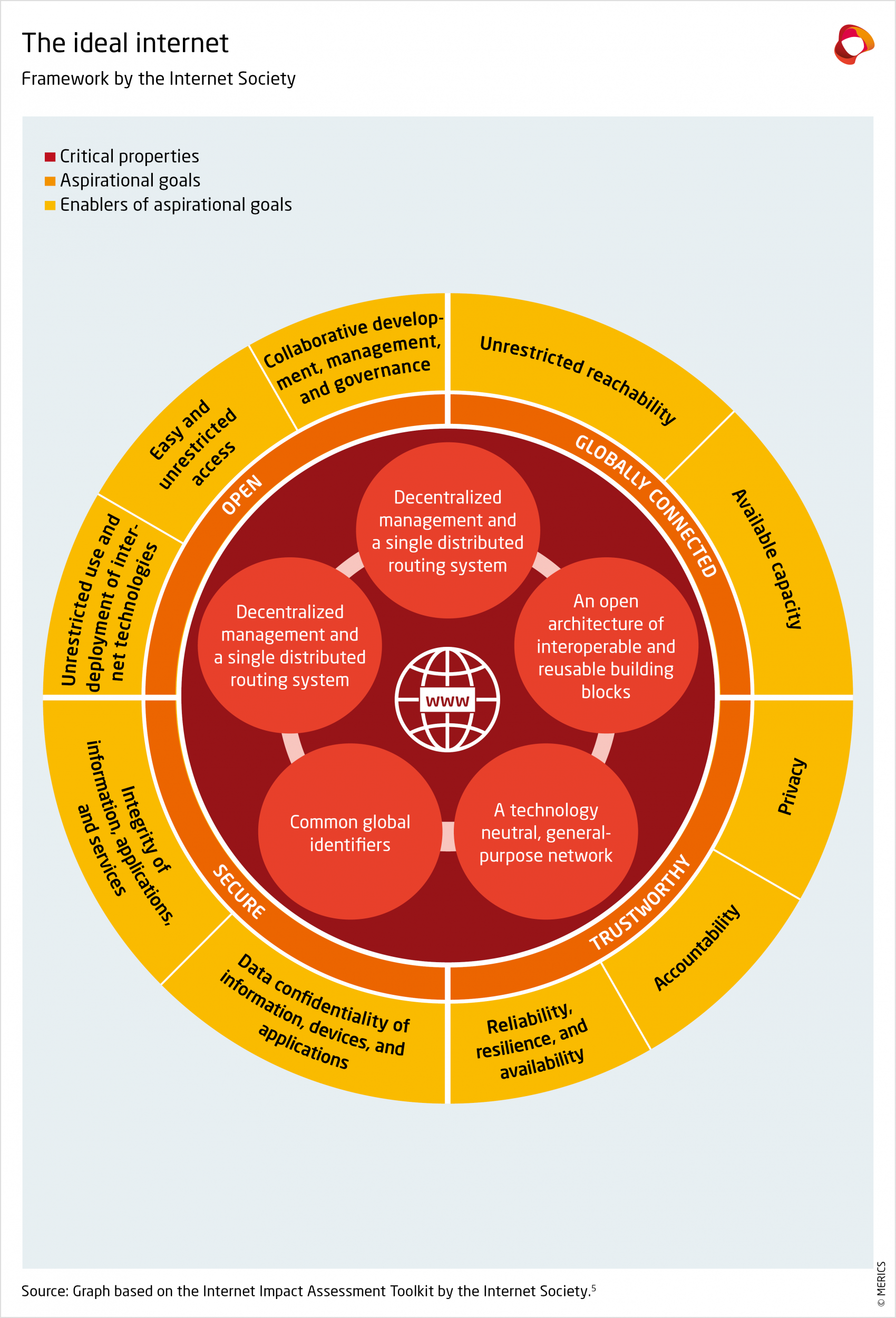

Each thematic chapter examines both types of fragmentation and their contributing factors. The underlying analytical framework is inspired by that of the Internet Society, a US advocacy non-profit that promotes the internet’s open development. Their framework of normative ideals for the internet (see Exhibit 1) aligns with the EU’s strategy, “Fit for the Digital Age”,6 and aims for an internet that is both open, globally connected, secure and trustworthy.

This report outlines how implementing this vision is complicated by the transformation of the “Great Firewall of China” into something that is much more structurally embedded in the way China’s internet links up with the rest of the world.

Large parts of China’s internet are already inaccessible for anyone without a Chinese ID and phone number. Foreign organizations and firms in China struggle to transfer data to their home organizations because of deliberately vague security regulations. Discussions over shared standards and norms are complicated by profound differences in terminology.

Relying on its multi-stakeholder model, various European actors should ask their Chinese counterparts for clarity and reciprocity. Dialogue is also needed to jointly prevent deep technological fragmentation, which is still relatively modest today, from extending to more areas and making inter-connectivity physically difficult. At the same time, Europe would be well-advised to de-risk from China and prepare for a more fundamentally fragmented internet.

Conclusion: How to overcome European indecision in shaping the future internet

Our analysis has shown how China implements internet governance that is fundamentally different from that of Europe. Across data flows, web applications, internet protocols and digital hardware, China’s vision and actions drive the fragmentation of the global internet. Occasionally it is also in Europe’s interest to indicate disagreement with standards and norms that China seeks to organize global consensus for. That means that Europe does not pursue a unified global internet at all cost. Within this context, we suggest what we believe are the most optimal positions and actions for Europe. These suggestions are organized along the four layers, because the speed and shape of fragmentation is different in each of them, requiring unique strategies to enable European actors – governments, companies and others – to regain influence over the future of the internet.

1. Data flows

- Demand regulatory clarity from Chinese authorities: Beijing has recently retreated from stringent restrictions on cross-border data transfers. However, the scope of key concepts like “important data” needs to be made more transparent.

- Prepare for added regulatory risk: The national security-related considerations in China’s regulatory regime challenge, in particular, firms in data-intensive sectors such as autonomous vehicles, pharma and intelligent manufacturing. They need to evaluate costs and benefits of their data strategies on the Chinese market, including ethical and reputational risks.

- Prepare for worst-case scenarios: Recent Chinese laws provide for retaliatory measures against actions by foreign governments, like for instance, China leveraging its data market for economic coercion and imposing tighter restrictions on access to the global internet.

- Review ICT equipment and software applications originating from China: The European Data Protection Board and the EU Agency for Cybersecurity could jointly establish a taskforce to get a better overview of tech firms headquartered in China that handle sensitive data in the EU, including both personal and non-personal data.

- Foster trusted data coalitions: To respond to the economic and political challenges emanating from China, the EU’s cyber diplomacy needs to offer appealing propositions for digital economy and connectivity partnerships.

2. Web applications

- Monitor the global rollout of PRC-made mobile software platforms and coordinate responses within UN bodies like the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) and multi- stakeholder bodies like w3c: Huawei’s operating system is unlikely to compete with Android and iOS in developed economies, but it may do so in developing countries. Quick apps-type features could bring technical fragmentation there.

- Review the EU’s readiness for super-apps: Existing regulation like the Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA) focus on US-based companies. The measures need to be reviewed to see how they can address challenges posed by Chinese products.

- Call on China to improve foreign access to its online ecosystem: Access and the open flow of information are increasingly difficult for businesses, diplomats, and researchers due to the use of pre-selected phone prefixes and geo-blocking. Privacy is at risk from real-name or phone-number registration.

- Prepare for loss of access: Stronger efforts are needed to preserve and archive online resources from the Chinese internet. Content is often available only briefly, or access is limited overall.

- Inform the public about risks posed by using Chinese apps and websites: Users joining Chinese platforms can become subject to Chinese laws and regulations, and they need to be familiarized with privacy risks of phone-number registration.

3. Internet protocols

- Coordination on technical language in standards development organizations: Understanding China’s often non-standard use of technical language requires expertise and time for a thorough analysis of Chinese proposals. Like-minded actors need to develop routines on how to swiftly coordinate during standard-setting conferences.

- Compile a dictionary of Chinese technical terms: Dedicated staff should look at Chinese domestic developments, because terminologies often appear first in domestic contexts before being used internationally.

- Uphold a multi-stakeholder approach to maintain credibility: Europe is drawing up a “fair share” contribution proposal for big tech platforms to contribute to developing digital infrastructure. The process for implementation has lacked transparency due to pressure from European telecommunications companies.

- Invite diverse stakeholders to standardization bodies: European governments should support SMEs, industry associations and NGOs in representing internet users’ interests at standardization events.

4. Digital hardware

- A consistent policy regarding Chinese hardware in European networks: This is needed, especially as China obstructs European firms’ access and Chinese laws are quite clear on companies needing to cooperate with security services. Europe should conduct a risk assessment, define “core networks” and “trustworthy vendors” and the possible risks of Chinese vendors, their impacts and likelihoods of these risks. A quantitative limit of 30 percent of hardware from any one country could be a possibility.

- Ensure Europe has diverse vendors for hardware through regulation and financial incentives: Network builders will struggle to stick to a 30 percent ceiling of components from one country in the short term as production is so concentrated.

- Expand export credits to European vendors: More support is needed for companies competing with big Chinese players like Huawei or HMN outside Europe.

- Coordinate European positions in global standards-setting forums: Governments should help improve the influence of European companies in global organizations. This needs a long-term strategy and research funding in areas like next-generation mobile internet standards.

- Expand the EU’s Digital Global Gateway: The initiative needs more funds to become a real alternative to China’s “Digital Silk Road”. Network buildup in the Global South requires easy and swift access to funding, meaningful participation of local people and companies, and training for countries to operate networks themselves.

- Maintain opportunities for constructive dialogue: European country-agnostic measures provide a basis to call out China. At the same time, Europe needs to keep China involved in the global hardware layer alongside the US to prevent commercial and regulatory fragmentation from escalating into technical fragmentation.

- Endnotes

-

1 | https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/declaration-future-internet

2 | https://archive.vn/1iXTf

3 | https://www.intgovforum.org/en/content/igf-2022-pn-internet-fragmentation

4 | https://www.weforum.org/reports/internet-fragmentation-an-overview/

5 | https://www.internetsociety.org/issues/internet-way-of-networking/internet-impact-assessment-toolkit/

6 | https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/events/high-level-multi-stakeholder-event-future-internet