Dual-use export controls + Beijing’s “genuine” multilateralism + China’s recruitment of researchers in Denmark

TOP STORY: EU beefs up ability to compete ahead of international discussions on rules

The Commission is living up to its word, and building up its ability to be assertive in international economic competition, says MERICS analyst, François Chimits.

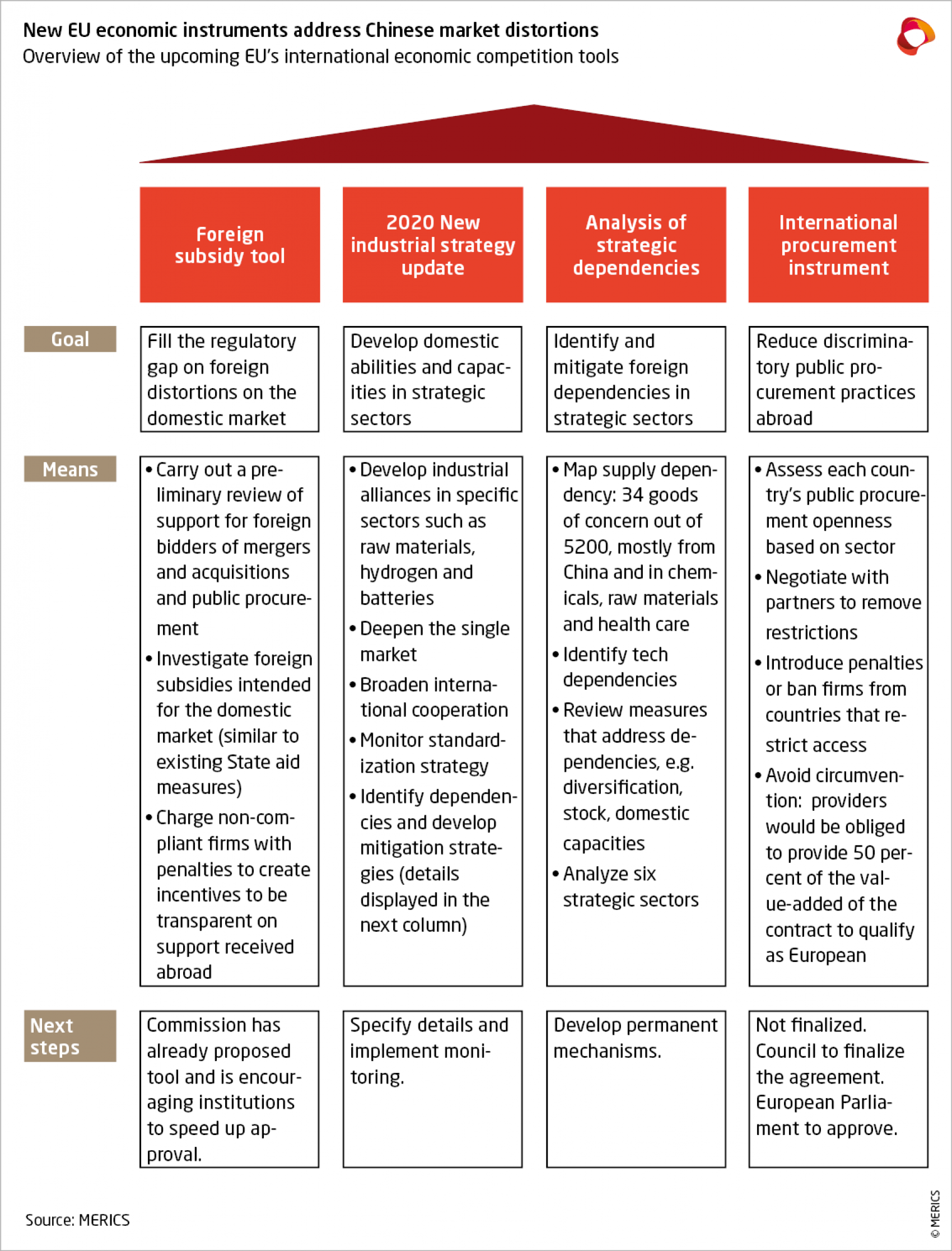

A look at recent activity provides plenty of evidence. Proposals from the European Commission over the past few weeks include a tool to tackle the domestic impact of foreign subsidies, a methodology for monitoring foreign economic vulnerabilities, an update of its 2020 industrial policy with specific efforts in strategic sectors and a standardization strategy on key technologies, and a regulation on Artificial Intelligence barring uses “contravening the Union values or violating fundamental rights”. Meanwhile, the Portuguese presidency of the Council has declared it wants to agree the International Procurement Instrument (IPI) by year-end, allowing the EU to deny access to public procurement for firms from countries without reciprocal access to public tenders. The EU has even activated a rarely used Trade Barriers Regulation. This comes on top of dynamic and innovative use of traditional trade defense.

MERICS take: Responding to criticism of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China, finalized at the end of 2020, the Commission replied that EU strategy on China should be assessed in the context of all its new tools. Indeed, these have the potential to rebalance its approach between cooperation and competition, especially as they fill a few empty spaces in the EU’s international competition toolbox. The foreign subsidy tool, for instance, would enable the EU to shield the Single Market from goods and services, produced by firms subsidized abroad or State sponsored acquisitions. They also reinforce the EU’s negotiation position ahead of discussions about international rules on trade and market access.

What to watch: These new tools are all still at the proposition stage and there is quite a way to go before they can be used. Even then, the EU would need to demonstrate its resoluteness and ability to use them to make the changes effective. Such efforts are likely to be part of international discussions, first and foremost with the United States and China. Macron and Merkel are reportedly planning joint trips to both countries, while Biden – whose administration has yet to clarify its positions regarding Chinese distortive economic practices – is expected in Europe in June.

Read more:

- European Commission: Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market

- European Commission: Updating the 2020 New Industrial Strategy: Building a stronger Single Market for Europe’s recovery

- European Commission: Strategic dependencies and capacities

- European Commission: Trade barriers: EU concludes two examinations on ceramic tiles and on Tequila

- BDI [DE]: Level playing field in international competition

- Politico: EU readies response to Biden’s ‘Buy American’ pitch

- MERICS: The EU targets distortions in the Chinese aluminum value chain

EU reform of dual-use export controls is a step toward addressing human rights risks in tech value chains

The official endorsement of the reformed EU “Dual-Use Regulation” on May 6 is an important step towards preventing European technologies from being used to enable human rights abuses abroad. Under the new rules, companies seeking to export cyber-surveillance technologies will need to obtain a government license which will take into consideration the potential for the technology to be used for “internal repression” and “serious violations of international human rights”.

Technology is a key pillar of the Chinese Party-State's strategy for controlling ethnic minority populations in Xinjiang. The widespread human rights violations in the region led the EU to impose sanctions on China in March. While Chinese tech firms supply most of the hardware and software for Xinjiang’s public security authorities, the involvement of Western companies, including those based in the EU, has attracted growing attention from media and human rights organizations.

MERICS take: While the reform is a milestone, effective implementation is likely to prove challenging. When it comes to Xinjiang, it can be difficult to access information about the human rights risks associated with specific technologies. Companies winning surveillance contracts in the region are often integrators that bundle goods and services from multiple suppliers. As The Intercept's investigation into American computer software giant Oracle revealed, Western tech firms in China work with networks of brokers that may resell their products to police authorities. The Oracle case and other investigations show how general-purpose technology can be used to underpin data-driven policing.

But exports are only part of the story. Some Chinese firms implicated in Xinjiang abuses are global market leaders with an extensive presence in the EU. In April, the European Parliament removed thermal cameras it had procured from Chinese state-owned video surveillance manufacturer Hikvision, citing concerns over the company’s complicity in human rights abuses. Public authorities across Europe routinely source hardware and software from this and other compromised providers.

Another regulatory blind spot is the transfer of technology and know-how through research collaborations with companies and universities. Last year, a Politiken investigation revealed how Hikvision had worked with a Danish university on an algorithm that could be used for mass monitoring. Early this year, the University of Manchester ended a research project with China Electronics Technology Group (CETC), one of the leading players in Xinjiang’s surveillance market, over the company’s links to rights abuses.

What to watch: Export controls can only be part of a broader toolkit that addresses human rights risks within tech value chains. Several instruments are in the works. This quarter, the European Commission is due to propose an EU-wide human rights due diligence law. The provisions proposed by the Parliament, which include language on public procurement, would hold businesses accountable for human rights violations within their entire value chains. While enforcement of dual-use export controls in the EU’s research landscape remains a work in progress, the Commission and member states are finalizing non-binding recommendations to provide guidance for research organizations and national authorities.

Read more:

- Amnesty International: EU companies selling surveillance tools to China’s human rights abusers

- ASPI: Mapping more of China's tech giants: AI and surveillance

- Politiken [DK]: Aalborg University has helped controversial Chinese company that contributes to the persecution and surveillance of millions

- IPVM: EU Parliament Removes Hikvision, Citing Human Rights Abuses

- The Independent: University of Manchester ends research project with Chinese firm over alleged links to Uighur persecution

- The Intercept: How a Chinese surveillance broker became Oracle’s “partner of the year”

China calls for “genuine” multilateralism - What this means for the EU

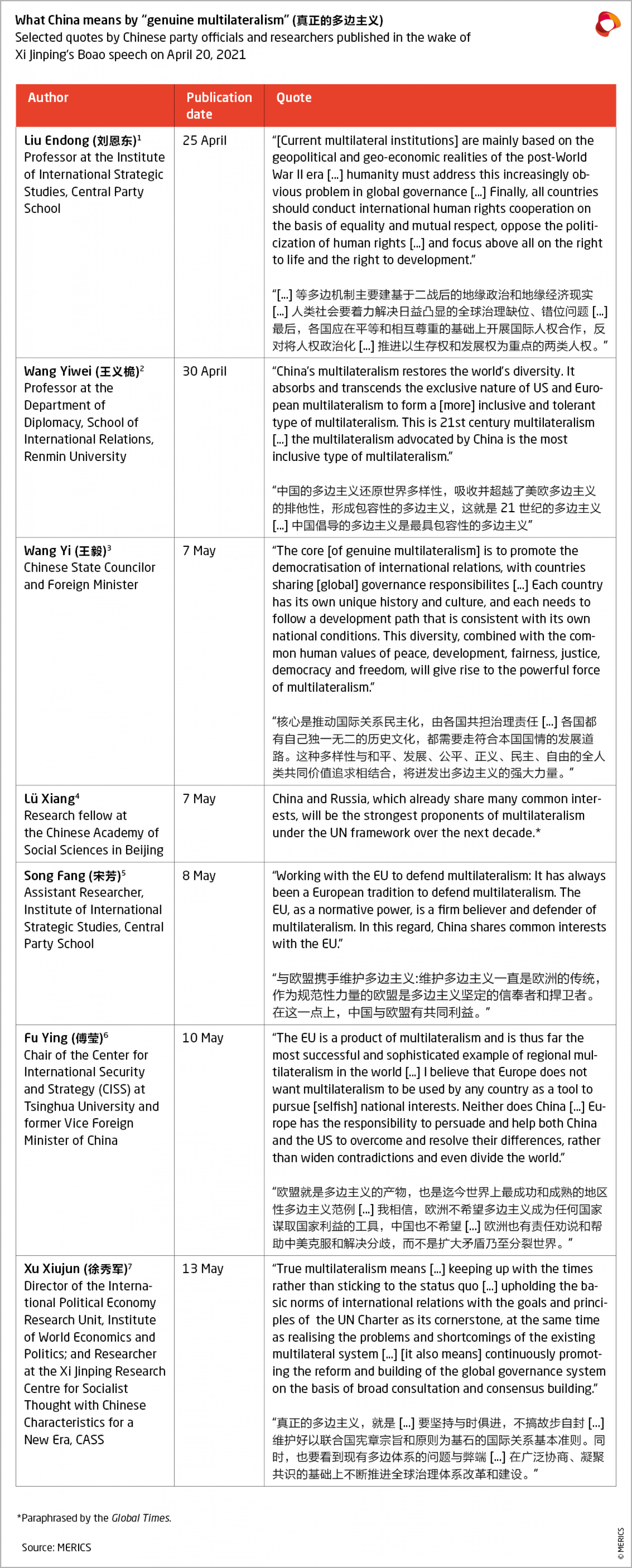

In his speech at the Boao Forum for Asia on April 20, Xi Jinping reiterated China’s call for the world to adhere to “genuine multilateralism” (真正的多边主义) and for “certain countries” to stop pursuing unilateralism under the guise of multilateralism. His message appeared destined both for his Asian counterparts and for those democratic alliances preparing to convene. Since then, party officials and researchers in China have been expounding on what this new form of international engagement might entail. Their assessments, presented below, differ less in content than in tone.

Genuine multilateralism with Chinese characteristics

According to these Chinese experts, “genuine multilateralism” is the next stage of international relations – a more “democratic”, “peaceful” and “inclusive” stage, one that will replace the western-controlled order by a purportedly “fairer”, more “diverse” and “tolerant” one. This new type of multilateralism is portrayed as being pro-multipolarity and anti-hegemony, pro-globalization and anti-protectionism. It will involve reforming the current global governance system, they say, to give a greater voice to all developing countries.

These researchers are adamant that the UN should form the bedrock of multilateralism, followed by “key” multilateral frameworks such as the WTO, the G20 and the Belt and Road Initiative. They insist that this new order should be underpinned by international law and the protection of human rights – understood primarily as people’s right to development (发展权) and right to subsistence (生存权).

“Genuine multilateralism”, as they see it, is synonymous with protecting national sovereignty and should never involve interfering with differing ideologies and development models. They repeatedly contrast Chinese-style multilateralism with US-style multilateralism, criticized for its pursuit of “selfish” interests and interventionism. Building “small cliques”, such as the G7, D10 or Quad, is described as the archetype of power politics (强权政治) and the antithesis of “genuine multilateralism”.

The EU is at times characterized as “the most successful example of regional multilateralism” and at others as straying dangerously towards US-like multilateralism. Nevertheless, most believe that the EU could still shift “in the right direction” and help China build its “community with a shared future for mankind” of which “genuine multilateralism” is said to be a key part of.

Significance for the EU

China is trying to present itself as a leader of the developing world and a catalyst for democratization of international order, at the same time discrediting Western initiatives as exclusive and self-serving. While this may not be convincing in Brussels, Berlin or Paris, these are not the target audience, but rather those developing countries that can increase China’s position in multilateral frameworks. For example, in October 2020 Beijing mustered support from 45, mostly developing, countries for a motion opposing the UN statement condemning China’s polices in Xinjiang. More recently, on May 21 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that nearly 80 WHO members opposed admission of Taiwan to the World Health Assembly.

While not an entirely new tool in China’s toolbox, the recent intensification of these rhetoric around multilateralism may be a reaction to increased activity of groupings such as G7 or Quad. In regard to the EU, China would like to discourage the bloc from coordinating with the United States and encourage it to “persuade and help China and the US to grapple with their differences, instead of expanding contradictions and even splitting the world.”

But for the EU, China’s narrative on multilateralism points to a wider challenge – the need to reinvigorate engagement with developing countries and propose a vision of multilateralism that they will want to endorse. With the EU’s Connectivity Strategy so far yielding limited results, Germany’s white paper on multilateralism, released on May 19, proposing “stable, just and effective international order”, is the most recent step in that direction. But further steps are needed.

Read more:

- Central Party School [CN]: The United Nations and the new issues of global governance amid great changes (Quote 1)

- Central Party School [CN]: What multilateralism should look like in the 21st century (Quote 2)

- CSSN [CN]: Promotion of the rule of law in international relations is the key to multilateralism (Quote 3)

- Global Times: Washington's 'small clique' politics exposed as China, Russia battle with US over 'rules', 'multilateralism' at UN (Quote 4)

- Central Party School [CN]: The EU's difficult choice between China and the United States – An analysis through the lens of "cakeism” (Quote 5)

- Guancha [CN]: China and Multilateralism (Quote 6)

- People’s Daily [CN]: The world needs genuine multilateralism (Quote 7)

- Munich Security Council: Wang Yi on multilateralism and relations between China and the West

China’s recruitment of researchers in Denmark reveals weaknesses in EU’s knowledge protection

Eight university researchers working in the wind turbine industry in Denmark have been reported connected to a Chinese program suspected of being a vehicle for industrial espionage. Green energy is an area that China wants to dominate by 2025.

The Danish case is the latest addition to ongoing investigations into illegal knowledge transfers from the United States, Canada, Australia and Japan to China under its Thousand Talents Program. The program has been recruiting scores of top researchers in the West for years, particularly in key areas such as biotech, nanotechnology, energy, and space.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute estimates that the Chinese government has established around 600 “overseas talent-recruitment stations” around the world. Lack of transparency has long been a hallmark, with researchers often failing to disclose their association with the program or patents filed in China. Without access to contracts and laboratories in China, it is difficult to prove patent theft, so most investigations focus on researchers suspected of concealing ties to and work for China.

Analysis: The EU’s Communication on the Global Approach in Research and Innovation calls for a leveling playing field, protection of intellectual property rights and, for the first time, limits foreign participation in the Horizon Europe program in cases where the EU’s strategic assets, interests, autonomy, or security are concerned.

However, the pace of research and development in China still creates a dilemma for European universities that want to collaborate with Chinese counterparts. While they increasingly realize that they need to protect their own research competitiveness, European universities are still largely unaware of the Thousand Talent Program and the risks associated with research cooperation with China. When quizzed about this challenge, they say they lack the capacities to run due diligence of Chinese partner universities or the mechanisms to check that the scope of cooperation does not exceed standard scientific practice.

What to watch: Denmark’s strategic partnership with China was scheduled to be extended last year, but that has now been postponed indefinitely. This may lead to reduced cooperation in the green tech industry between Denmark and China, including research.

At the EU level, it would be worth paying attention to the guidelines the European Commission intends to present this year that deal with foreign interference targeting EU research organizations and higher education institutions.

Read more:

- Politiken [DK]: China hires wind turbine researchers through talent program suspected of industrial espionage

- European Commission: Global Approach to Research and Innovation - Europe’s strategy for international cooperation in a changing world

- NPR: Harvard Professor's Arrest Raises Questions About Scientific Openness

- The Diplomat: Countering China’s Influence Campaigns at European Universities

- The Strait Times: China using network of researchers to recruit foreign personnel

Beyond politics? The auto industry continues to build its two-way street between the EU and China

European carmakers face a new challenger on their home turf: Chinese electric vehicle (EV) makers. On May 6, China’s Tesla challenger NIO announced its market entry in Norway. Other China-based EV makers, like Xpeng, have been exporting to European countries for several months.

At the same time, and seemingly unfazed by the current political arguments around the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), European carmakers continue to integrate China into their globalized production plans and have doubled down on investment in China. Earlier this year, BMW started exporting its full-electric iX3 from Shenyang and Volkswagen started construction of a state-of-the-art EV plant in Anhui in late April.

MERICS take: Despite political tensions, automotive connections between the EU and China are becoming stronger. However, it is no longer a one-way street in which European carmakers invest in and export to China. Rather, wishing to profit from the dynamism of the leading market for EVs, European companies are increasingly investing in China to serve global markets.

Fuelled by these investments, Chinese EV exports to Europe are also picking up. Leading Chinese EV-makers, but increasingly also foreign carmakers in China like BMW and Tesla, have set their sights on Europe, where high purchasing subsidies and the phaseout of the internal combustion engine promises healthy profits. Indeed, Chinese exports of new energy vehicles (NEV) – a category that includes pure-electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids and fuel cell vehicles – have surged in the last two years. In 2020, China exported over 100,000 units, with the majority going to European countries among which Belgium, the UK and Germany ranked top.

While export numbers are small for now, China is keen to have several of its indigenous brands rank among the global top ten automotive brands by 2025 and is using its domestic economy as a lever to attract global production forces. In the automotive sector the strategy seems to be paying off, despite geopolitical tensions.

What to watch : Chinese and European carmakers in China will continue to unveil export plans to Europe. We should also expect that some of the major Chinese players in the field will follow in the footsteps of Chinese battery makers, Svolt and CATL, and try to localize production in the EU.

These dynamics could increase choice and the attractiveness of e-mobility, which would be good news for consumers and EU climate ambitions. Still, it is worth paying greater attention to how this might affect the EU’s market and industry, especially as some of the Chinese-based EV makers benefit from substantial government subsidies.

Read more:

- Electrive: Electric vehicle industrial facility ‘Neo Park’ under construction in Anhui

- The Wire China: Tesla’s China Endgame

- China Daily: Volvo's China-made SUVs exported to European market

- Volkswagen: Start of construction of new electric car plant in China

- Caixin Global: BYD Fleshes Out Plans to Sell Electric Cars in Norway